Earlier this spring, Buzz the Bee disappeared from Honey Nut Cheerios boxes in Canada. Burt's Bees dropped the letter B from its lip balm products. Are these clever marketing ploys? Perhaps, but they were designed with a more noble purpose in mind: to raise awareness of disappearing honeybees. And, it's not just companies with apian spokespersons that are worried about their sudden flight: farmers, beekeepers, ecologists, and the USDA are just a few that fear what a bee-less world would look like.

What's the buzz on bees?

The western, or European, honeybee (Apis mellifera) – the most commonly kept of the honeybee species – has had a pretty bad decade, and the problems seem to only keep getting worse. A recent survey found that beekeepers in the United States lost 44 percent of their colonies in the past year, which is the second highest annual loss in the past 10 years.

In addition, the survey found that summer losses were roughly equal to winter losses. This is particularly worrisome and something that the researchers didn't even think to look at when they began the study a decade ago. Summer is when flowers are most abundant and bee colonies should be healthiest – colony loss should be minimal!

Unfortunately, much of the increased levels of colony loss is the result of the oft-reported Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). CCD is a distinct type of colony loss in that only the worker bees disappear from a colony – the queen, larvae, a number of nurse bees, and plenty of food remain in the hive. Interestingly, rival colonies and hive pests rarely raid the afflicted hive for some time after the colony's collapse, implying that the hive's enemies know something is wrong. However, the reason for this avoidance isn't known.

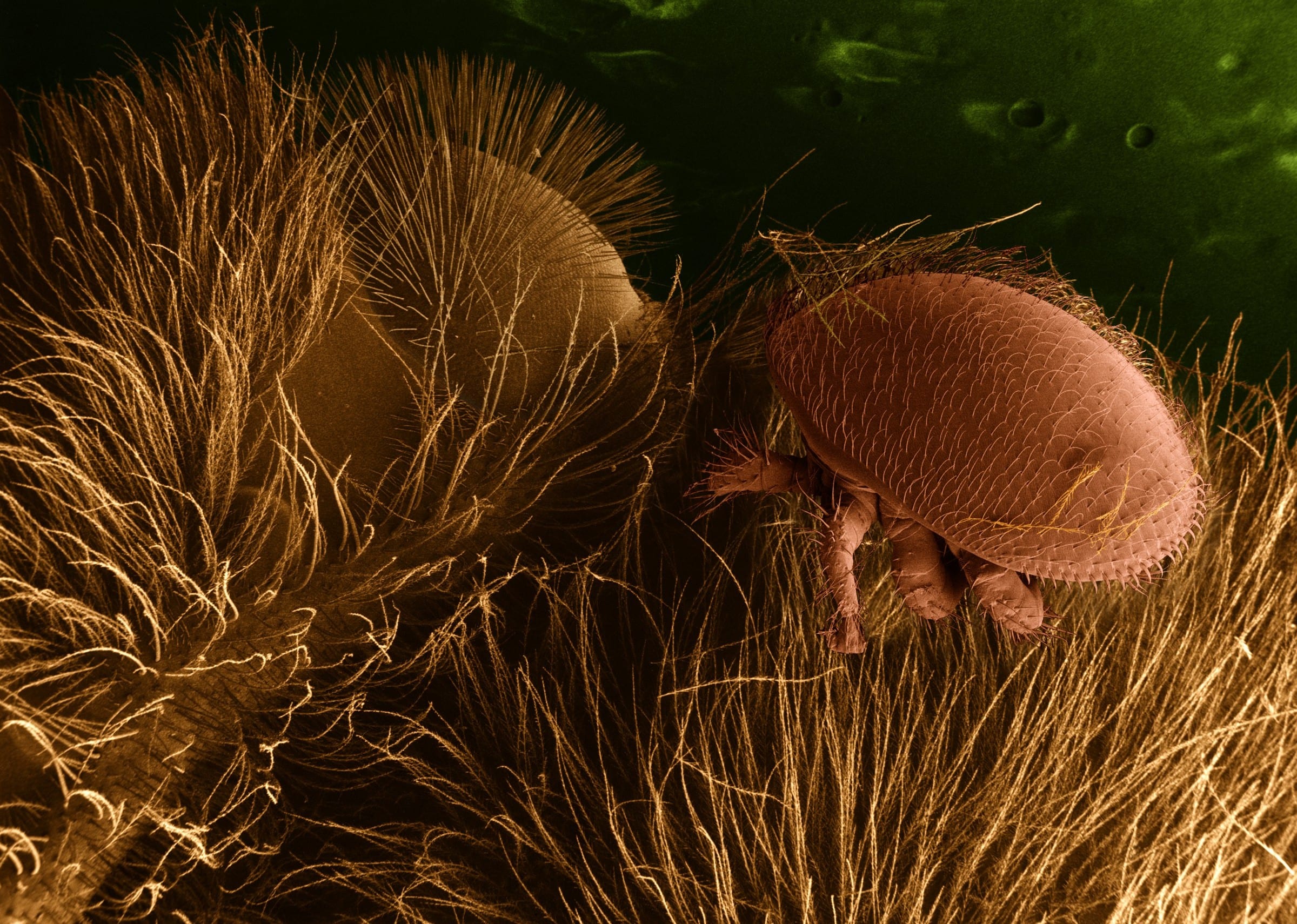

The reasons for the dramatic losses remain inconclusive, though there are a number of probable leads and there is probably some overlap between the causes of CCD and complete loss. The most important seem to be parasites: Nosema (Nosema spp.), a disease-causing fungus, and the Varroa mite (Varroa destructor), which feeds on bees' hemolymph (i.e. the ‘blood' found in insects) and passes viral diseases in the process. In fact, in one recent study, 50 percent of the sampled honeybee colonies had Varroa mite loads that exceeded levels that colonies can adequately handle. Failing to treat for mites, poor nutrition (because of a lack of food sources in agricultural settings), and exposure to pesticides (like neonicotinoids) most likely make bees more susceptible to parasites. All this said, every conceivable cause is still a possibility: undiscovered diseases, chemicals, and even poor management practices.

#BringBackTheBees

The declining bee populations have attracted a lot of attention – even President Obama announced a plan last year that will aim to speed up research on the causes of colony loss and CCD, as well as restore habitats that bees utilize. And, it makes sense that the President would focus so much attention on the plight of a small insect: it has been estimated that honeybees contribute around $15 billion to the US economy through their role as pollinators of fruits, vegetables, and other crops.

Considering the importance bees play to their products, Honey Nut Cheerios and Burt's Bees are also getting in on the effort. Honey Nut Cheerios sent out 115 million wildflower seeds to customers, and Burt's Bees has pledged to plant 1 billion wildflowers – efforts that are aimed at creating new bee habitat that would supplement the crop species they pollinate. I think most apiaries would agree that that's the bee's knees.

A transplant from Virginia (Hoos!), Greg Evans is a graduate student in the Plant Biology department at the University of Georgia studying herbicide and herbivory defenses in morning glories. When he's not tangled up in weeds, Greg enjoys Ultimate Frisbee, bowling, and board games. He can be reached at gevans@uga.edu. More from Greg Evans. A transplant from Virginia (Hoos!), Greg Evans is a graduate student in the Plant Biology department at the University of Georgia studying herbicide and herbivory defenses in morning glories. When he's not tangled up in weeds, Greg enjoys Ultimate Frisbee, bowling, and board games. He can be reached at gevans@uga.edu. More from Greg Evans. |

About the Author

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020