Cancer, a complex disease caused by an accumulation of mutations in our DNA, affects millions of individuals each year. Cancer poses a very serious threat, but is it contagious?

The short answer is “noâ€, at least for us humans. In humans, the only way to truly transfer cancer from one person to the next is by means of an organ transplant. No cases have been reported of cancer itself being contagious, but certain viruses, such as the familiar Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), have been linked to causing cancer in humans. This type of viral disease transmission is pretty unusual for cancer, but some examples do exist in other organisms outside the scope of humans.

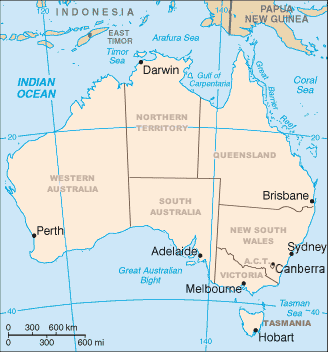

Tasmanian devils, the largest carnivorous mammals on earth, can pass on cancer like we can pass on a cold to someone else. These devils, roughly the size of a small dog, suffer from a facial cancer known as Devil Facial-Tumor Disease (DFTD). This disease results in large tumors on the face and neck, causing asphyxiation or starvation at an average of six months after onset. This facial cancer goes undetected by the devil's immune system, resulting in the growth of tumors until it is too late. But how does it spread from one devil to another? Devils are gregarious creatures. During acts such as feeding or mating, the devils can wound each other through biting, ultimately causing the spread of cancerous cells from one devil to another. This transmission of DFTD is so efficient that the origin of the disease has been linked back to a distinct region of Tasmania using genetic techniques on tumors sampled from a variety of affected devils. Tasmania is an island state of Australia located off its southeastern coast and the last remaining native range for the Tasmanian devil.

Initial reports of devils with Devil Facial-Tumor Disease cropped up around the mid 1990's. After just 10 years, estimates place about a 70% infection rate among the current population. It's approximated that up to 60% of the devil population has been decimated by DFTD since 1996. Unfortunately, since the discovery of the first incidence of Devil Facial-Tumor Disease (DFTD1), a second wave of Devil Facial-Tumor Disease (DFTD2) arose sometime between 2007-2010, further decimating the devil population.

This Tasmanian DFTD epidemic has brought the endangered species near the point of extinction, which is projected to occur in as little as 35 years if no action is taken. Luckily, conservation efforts have been instituted to relocate uninfected populations of devils to various zoos around the world, as well as the nearby Maria Island, located off the eastern coast of Tasmania. Researchers at the University of Tasmania are spearheading a large collaborative effort that is showing promising results for the testing of recently developed vaccines against DFTD. Reports from the researchers at the University of Tasmania have also noted that the devil’s themselves are evolving to combat this disease, showing genetic mutations that improve resistance and tolerance to DFTD. Hopefully these human-facilitated efforts in combination with the naturally occurring mutations can lead to a successful and robust recovery of the Tasmanian devil population.

Ultimately, these devils provide an interesting and unusual case of transmissible cancer that could be used to further cancer research. Similar diseases have been documented in both domestic dogs and Syrian hamsters that seem to show related mechanisms for cancer establishment and metastasis (spreading of the disease to new locations in the organism). These animals have the potential to confer valuable information regarding basic tumor biology, tumor evolution, and common tumor transmission mechanisms to human studies.

Ben Luttinen is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Genetics studying the development of beneficial viruses in parasitoid wasps. In his spare time he enjoys watching movies, playing golf, and the occasional drink. You can reach ben at benjamin.luttinen@uga.edu.

Ben Luttinen is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Genetics studying the development of beneficial viruses in parasitoid wasps. In his spare time he enjoys watching movies, playing golf, and the occasional drink. You can reach ben at benjamin.luttinen@uga.edu.

About the Author

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

-

athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020