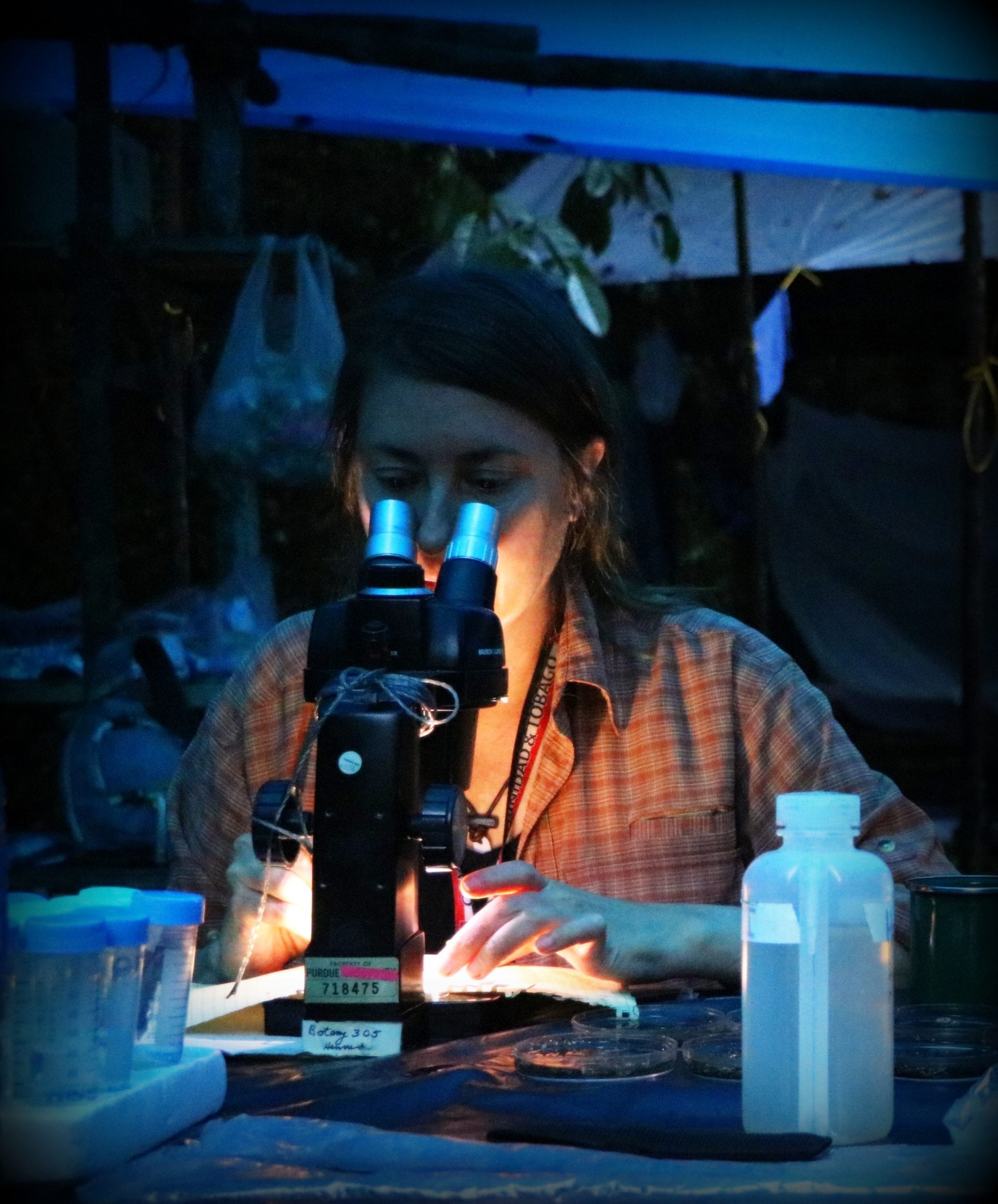

Dr. M. Cathie Aime is a Professor of Botany and Plant Pathology and Director of the Arthur Fungarium and Kriebel Herbaria at the University of Purdue. Her lab specializes on the biology of rust fungi as well as the biodiversity of tropical fungi, which has led her research to have an international focus. Interestingly enough, Dr. Aime didn’t follow the traditional method to academia by any means.

Can you describe your undergraduate experience?

I dropped out of undergraduate school in my third year to take care of my grandmother in New Orleans. I was a musician, played in a bunch of bands — even toured. I worked in bookstores and as a waitress to support my music habit for about 10 years. When I turned 30, I told myself, “You're not going to make it as a musician. You should do something with your life.†So I decided to finish my undergrad degree and eventually got my PhD in mycology.

How did you become interested in mycology?

My last course in undergrad at Virginia Tech was in mycology. I didn't know anything going in — other than that mushrooms sounded cool. Sure enough, it's what changed my life. I had a really good professor, so I became fascinated with fungi and how much there was unknown about them. He (Orson Miller) convinced me to go to grad school, and I ended up staying at Virginia Tech to work with him.

What inspired you to stay in academia?

Really, everything from that point is about Orson (Miller); he was a fantastic teacher. Without his encouragement, his explanation of academia, and grad school and research, I probably wouldn't have considered research as a career. I knew people did it; I just didn't know how people did it. When I started in the lab, I knew that’s what I wanted—to do research and be in academia, just be in that environment.

How did you get involved with field operations for your biodiversity work?

When I dropped out, there was no such thing as molecular biology. In those ten years, the entire field of biology had changed. At Virginia Tech we didn’t have the facilities to do molecular biology, but at Duke (about 3 1/2 hours away) there was a mycologist doing molecular mycology. I would drive down there every weekend and holiday and work in his lab. When I was there, I met a grad student who had previously worked in Guyana as a botanist. We decided to do a one year study in Guyana to look at the fungi there. It had nothing to do with my research; it was just something fun to do as a side project. Of course this side project has been going on for 20 years now.

What was the hardest part about doing these field experiments/trips?

All of the permissions and permits from the local governments. Wherever you are doing the work, getting the permits is always time consuming and what you need is different for every country. Even in Guyana, where we have been for 20 years, the rules change every year. It's expensive to get the permits for doing research, and additionally you need to get separate permits to export whatever you are taking out of the country.

Places like Guyana have no overland routes to where we go, so we have to take little charter planes that can land at abandoned mining camps. The planes take 600 pounds, so we have to figure out what we can take and how many planes can take us. The weather is always bad. Sometimes you're sitting on the airstrip on the other side for days, waiting for the weather to clear up so a plane can come back and get you.

Usually, buying all the gear and rations goes well. But if you forget something, like your salt or your toothpaste, you are out for 2 months. Building the camps itself isn’t so difficult because we keep going back to the same place. One year, we had a lightweight aluminum canoe to get us around, but there was a flood and the canoe washed away. There we were, stuck in the middle of nowhere, with no boat, no way to get back to where the plane was supposed to pick us up, and no way to signal anybody. Eventually, we got back down to the airstrip after building a dugout.

So how do you pick your field work locations, a lack of studies or that there is something interesting going on there?

It’s a little more haphazard. For instance, in Vanuatu, in the middle of the South Pacific no one has studied the microfungal flora. I know that there's a lot of endemism in those islands, but surveying there requires immense resources and infrastructure. I got lucky when I was offered an opportunity to hitch a ride with a research group led by the New York Botanical Gardens. Some of the other locations, like Queensland, were very targeted. There was a specific fungus in the rainforest that my post doc and I needed to resolve a tangled problem. After a few years of trying to get samples or work around it we just said “let's go and get it ourselves!â€. In Cameroon we got funding to set up a long-term study to match that in Guyana. That was a very deliberately chosen forest and region to test specific biogeographical hypotheses. So, overall, a mixture of different reasons.

With all the international work that you do, how do you maintain an international student presence in your lab?

I don’t know if it was so deliberate at first. When I go to different countries, I often get to work with local students that are interested in mycology but don't have access to rigorous mycological training, especially in the developing world. If a student is passionate and shows promise, then I'm going to do everything I can to get them into my program. A lot of my students are that way. The way I see it, your productive time as an academic is limited. I started in my 30's, so I have 20 to 30 good years in academia—what do I really want to do with that? I want to train students that are passionate about mycology and the environment, who will go on to train the next generation around the world.

About the Author

Inam Jameel is a PhD student in the Department of Genetics at UGA. He is interested in how natural populations adapt to rapidly changing environments. When not in the greenhouse or in the lab, Inam likes to run, attend concerts, watch the Washington Capitals, and do poorly at trivia. He can be reached at inam@uga.edu or @evo_inam.

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/March 18, 2022

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/November 17, 2020

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/April 28, 2020