While I'm often left paralyzed by apple choice in Kroger, I know the breadth of options at grocery stores mask a far different reality: we've lost roughly 90% of the world's crop varieties in the past 100 years. This threat to future food security is referred to as genetic erosion and primarily attributed to the proliferation of modern cultivars, which displace local crop varieties. Conservation methods to maintain crop biodiversity rely on either the use of external seed banks and greenhouses (ex situ) or through continued cultivation on farmland (in situ).

As I've previously alluded to, ex situ conservation is imperfect. While there is a bleak romance to seed banks as our planet's emergency supply closet, this shouldn't be our only option. One of the most obvious drawbacks are the physical limitations to conserving all plant genetic material. Everything cannot be banked – for instance Svalbard has roughly 5,000 of the estimated 390,900 existing plant species in its collections- so then which plants are deemed worthy of this protection? And who gets to make those decisions?

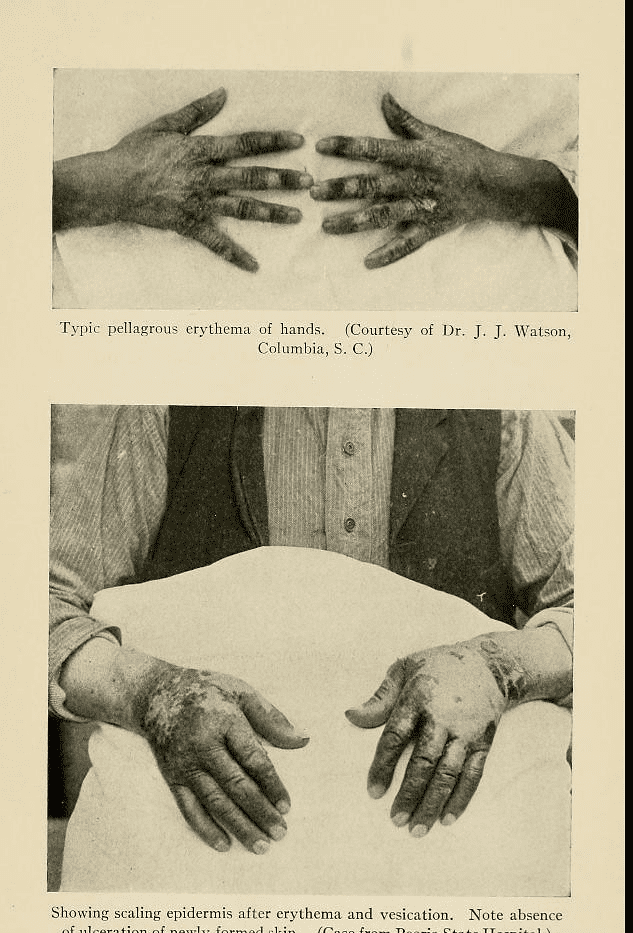

Then there's a messier issue I will distill to: seeds have context. Germplasm is not a standalone technology, but rather interwoven to its ecological and cultural surroundings. Severing such ties without mindful consideration has consequences. One such example can be found in the 16th century proliferation of maize in Europe. The crop's relative affordability led to its quick adoption as a food item among Italian peasantry. But lost in the grand crossing of the Atlantic was the concept of nixtamalization, the traditional Mesoamerican alkali treatment of corn, which ensures the bioavailability of niacin (also known as essential vitamin B3). Without nixtamalization, and with corn as the primary food source, chronic niacin deficiencies emerged in a scourge of pellagra in Italy, a disease marked by neatly descending “Dsâ€: diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death. This same pattern reemerged in the American south in the late 19th century, taking thousands of lives. It's embarrassing to think that a glint of respect for the cultural knowledge surrounding food preparation could have averted centuries of human suffering.

What use is a seed if we do not know how to appropriately grow, process, and eat it? Storing seeds in a vault decontextualizes plants, necessitating a complementary mode of conservation that maintains the robust cultural knowledge surrounding crop variety production and consumption. This can be found in in situ conservation, where continued cultivation on farmland ensures maintenance of both germplasm and its kindred socio-ecological system. Critical to this type of conservation is traditional and indigenous knowledge.

The Potato Park in Peru is one example of a successful landscape-scale in situ conservation model in the Andean region, which encompasses two of Vavilov's centers of origin. The site is classified as an Indigenous Biocultural Heritage Area, and aims to protect the region's incredible biodiversity and improve indigenous livelihoods through use of traditional knowledge. Methods of crop cultivation here are emblematic of traditional modes of farming more generally, in that they are incredibly complex and low-input, with a typical farm plot containing between 250-300 potato varieties. Success of such farming systems is highly reliant on deep agro-ecological knowledge.

However, traditional farmers are continually facing incentives to switch to higher yielding, profitable commercial cultivars and more generally, a global economy that devalues traditional modes of existence. This has been displayed in the indigenous Arawakan women of Venezuela, who have customarily cultivated over 70 varieties of bitter manioc (cassava). With cultural shifts to an education system that encourages the abandonment of traditional modes of crop production, there has been a concurrent erosion of traditional cultivation, knowledge and the associated agrobiodiversity.

Maintenance of genetic diversity is a global public service. Thus, structures should be put in place to support both traditional varieties and their corresponding knowledge. Some suggestions range from community based conservation approaches with designated funds for compensating communities for income losses, to establishing separate “farmers rights†legal systems that explicitly recognize farming community's contributions. But instead, we primarily have western Intellectual Property structures that incentivize commoditization and individual ownership. While I am no etymologist, there does seem to be a glaringly obvious “culture†in agriculture that should be paid heed.

The path to extinction is paved by both loss of genetic diversity and loss of knowledge, and so we need ex situ and in situ conservation hand in hand.

__

It's worth mentioning the various directionalities in human relations with plant material. While most of us are attuned to the thinking of humans domineering plants to suit our needs, plant genetic material can similarly influence humanity. Landrace varieties that are interwoven with their local ecologies demand that we too pay more attention to our immediate environment in order to successfully harvest them. In a way, fostering this relationship with localized plant material can produce subtle human-environment relational shifts away from domination and towards respect. And because I am writing for a website with the word “science†in the title I will spare you from the philosophical zenith of this train of thought, but will leave some links in case anyone cares to meander in that direction.

About the Author

Tara Conway is an M.S. student in Crop and Soil Sciences, where she is working towards the development of a perennial grain sorghum. She is originally from Chicago, IL. Her work experience spans from capuchin monkeys to soap formulating. You can reach her at tmc66335@uga.edu, where she would like to know which bulldog statue in town is your favorite. Hers is the Georgia Power one due to its peculiar boots. More from Tara Conway.

Tara Conway is an M.S. student in Crop and Soil Sciences, where she is working towards the development of a perennial grain sorghum. She is originally from Chicago, IL. Her work experience spans from capuchin monkeys to soap formulating. You can reach her at tmc66335@uga.edu, where she would like to know which bulldog statue in town is your favorite. Hers is the Georgia Power one due to its peculiar boots. More from Tara Conway.

Featured image credit: “Cobs of Corn” by Sam Fentress licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

About the Author

Tara Conway Tara Conway is an M.S. student in Crop and Soil Sciences, where she is working towards the development of a perennial grain sorghum. She is originally from Chicago, IL. Her work experience spans from capuchin monkeys to soap formulating. You can reach her at tmc66335@uga.edu, where she would like to know which bulldog statue in town is your favorite. Hers is the Georgia Power one due to its peculiar boots. More from Tara Conway.

-

Tara Conwayhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/tara-conway/October 30, 2019

-

Tara Conwayhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/tara-conway/September 30, 2019