A few months ago, a good friend of mine fell victim to a pervasive phone scam where he lost nearly $4,000 in a single afternoon. Despite being a smart guy he fell hook, line, and sinker for this scam. To his credit, this was not your typical internet scam but actually quite an elaborate one that used a healthy dose of fear tactics, such as impersonating an IRS agent and giving threats of arrest. But it got me thinking, there are some pretty transparent hoaxes out there that people fall prey to all the time. In a classic example of an obvious scam, a Nigerian Prince has $1,000,000 that needs to be quickly and quietly moved over to your grandmother's bank account for safekeeping. Of course, he offers to share a sizeable chunk of the money for her trouble. For most of us, this request is laughable and an obvious scam. But one thing most people don't realize is that the Nigerian Prince fraud is actually profitable to scammers because it is so transparently fake! This blog will explore the history and economics behind the Nigerian letter scam.

But first, what is a 419 scam?

The Nigerian letter fraud is commonly known as a “419†scam, after the 419th section of the Nigerian code that criminalizes this particular flavor of fraud [1]. Often, a victim is asked to help cover various legal fees, transportation fees, bribes, etc. until the victims can be reimbursed and rewarded for his or her assistance. Because the large pool of money doesn't actually exist, the victim never recovers his or her funds [1]. The Nigerian 419 scam and other cyber crimes bamboozled (yes, I said bamboozled) Americans out of a reported $782 million in 2013 alone [2]! So, clearly someone is falling for them. How long has this been going on, and what is so convincing about Nigerian Princes?

These 419-type scams are not a blight limited to the digital age. Budding historian Robert Whitaker documents a 419 scam that first occurred back in 1905 [3]. According to Whitaker, the scam proceeded through beautifully hand-written letters sent by supposed Spanish prisoner “Luis Ramos†to Mr. Paul Webb, a British shopkeeper. The scam is fairly elaborate, but the story involves the secretary of a famous general who deposits £37,000 in an English bank, becomes imprisoned by the Spanish military, contracts hepatitis, and dies heirless in the prison. Letters from the Spanish military ask for a small cash advance (£57) to release all of “Luis's†possessions. Perhaps a scam like this was convincing in the early 1900s when people were naïve to this type of fraud and technological limitations kept the longest airplane flights to just under 13 seconds. But how can such a scam continue to trick people well into the 21st century?

The Economics of 419 scams

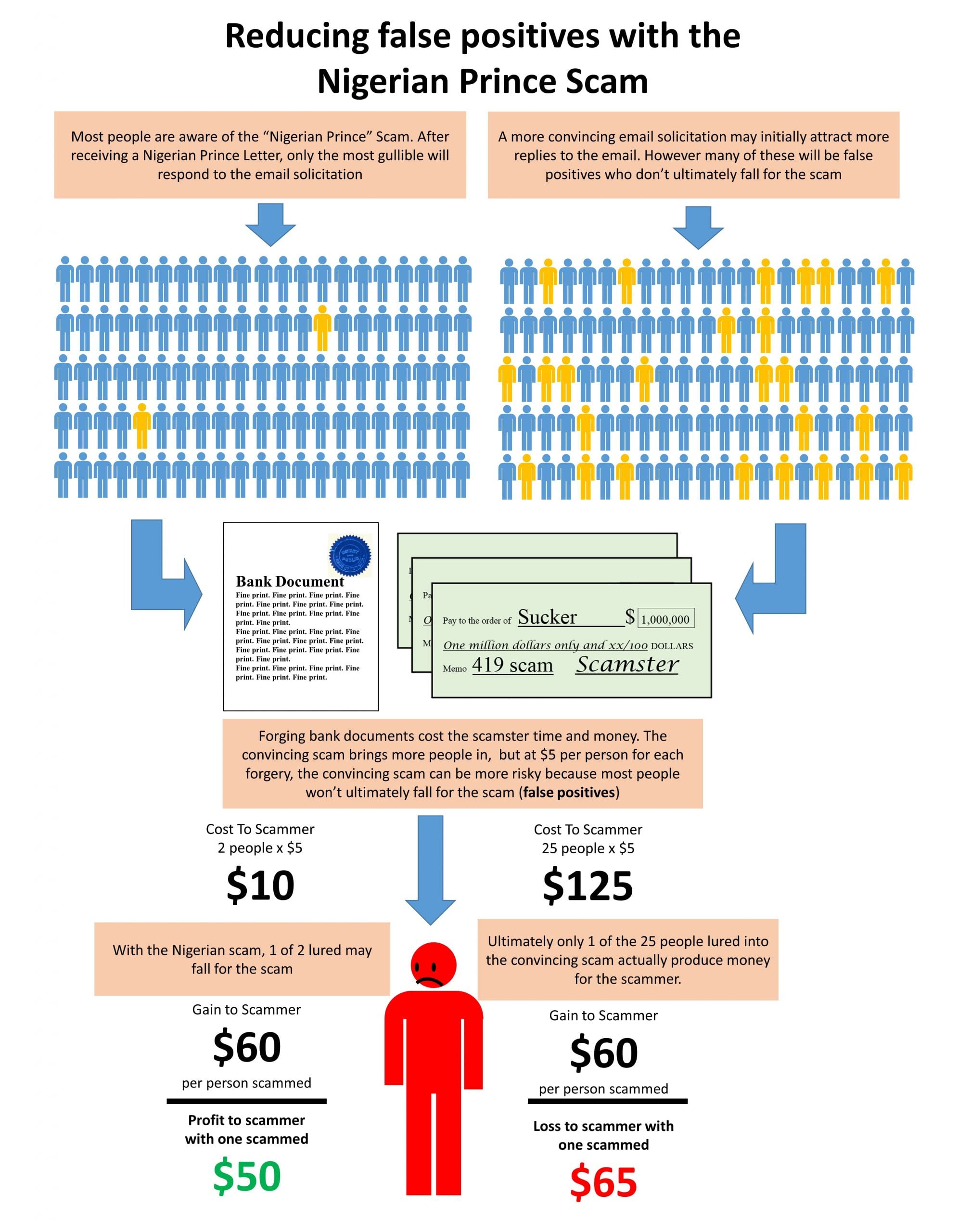

Microsoft Researcher Cormac Herley showed that the Nigerian letter scam is profitable partly because it is a well-known scam [4]. This may sound counterintuitive at first, until you think about the math and science behind the concept of false-positives. In the context of a 419 scam, a false positive is any person who is responds to the Nigerian letter, but who ultimately doesn't get duped. Any effort a scammer spends on a false positive gets wasted. Because it takes time and money to complete a scam, false positives cause a dilemma for scammers. If scammers try to victimize many people, then they have to deal with many false positives, and the fraudster wastes time making phone calls or falsifying documents. With too many false positives, the fraudster cannot profitably conduct “business.†On the other hand, if the fraudster doesn't try to scam enough people, he misses out on many potential victims.

If the cost to the scammer is nearly free, the scammer's best strategy is to victimize as many people as possible! This may explain why email spam is so prevalent. However, when people respond to a Nigerian letter scam, the scam becomes more elaborate and the scammer typically has to spend time forging documents and communicating with the victim in order to actually complete the scam. This is where the popularity of the “Nigerian Prince†comes into play, according to Herley.

Because the “Nigerian Prince†scam is so well known, the vast majority of people who receive a Nigerian letter know immediately that it is a scam and never respond. However, there is a very small (and gullible) fraction remaining that has never heard of the scam and respond to the bizarre request. To put some numbers on it, let's say 100 people are sent a Nigerian letter. Let's say 98 of these 100 know about this classic scam and never respond, but 2 naïve people reply to the letter. This seems bad for the scammer because the pool of potential victims is winnowed down from 100 to only 2 people. But remember, these 2 people have obviously never heard of the scam and are the most likely to fall for it. Any effort and money put into scamming these two victims will likely pay off for the scammer. However, if the scammer spent any time going after money on the remaining 98 people, he or she would most likely be wasting time and resources on victims that will not actually yield any profits for the scammer. By using a well-known “Nigerian Prince†story, the scammer has increased the profitability of his or her scheme by filtering out all of the would-be false positives.

If you wonder how people could fall for a 419 scam, then you are in the lucky majority of people that the scammer wants to filter out. Rather than trying to trick people with a novel scam, the classic Nigerian letter acts as a filter to find the most vulnerable internet users who haven't realized the scam is certainly too good to be true, rather than wasting time on false positives. This information doesn't help my buddy now, but I can at least understand how a seemingly novel scam can sound convincing, but are ultimately too good to be true. There doesn't seem to be much that individuals can do to fight scams rather than remaining cautious and reporting any fraudulent solicitations. The FBI offers a few tips for avoiding internet fraud like guarding account information carefully, being skeptical of any promise of large sums of money, and being careful with any kind of unsolicited email. While I can't condone this, if you think trolling scammers sounds fun, read up on scambaiting to see how vigilante internet users take advantage of being false positives to waste scammers time and resources to make it less profitable.

If you wonder how people could fall for a 419 scam, then you are in the lucky majority of people that the scammer wants to filter out. Rather than trying to trick people with a novel scam, the classic Nigerian letter acts as a filter to find the most vulnerable internet users who haven't realized the scam is certainly too good to be true, rather than wasting time on false positives. This information doesn't help my buddy now, but I can at least understand how a seemingly novel scam can sound convincing, but are ultimately too good to be true. There doesn't seem to be much that individuals can do to fight scams rather than remaining cautious and reporting any fraudulent solicitations. The FBI offers a few tips for avoiding internet fraud like guarding account information carefully, being skeptical of any promise of large sums of money, and being careful with any kind of unsolicited email. While I can't condone this, if you think trolling scammers sounds fun, read up on scambaiting to see how vigilante internet users take advantage of being false positives to waste scammers time and resources to make it less profitable.

About the author

Jeffery B. Cannon is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia researching how disturbances such as wind and fire shape forest ecosystems. He loves science, the outdoors, and enjoys running and brewing beer. You can connect with Jeff on Twitter @JefferyBCannon or by email: jbc165@gmail.com

Jeffery B. Cannon is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia researching how disturbances such as wind and fire shape forest ecosystems. He loves science, the outdoors, and enjoys running and brewing beer. You can connect with Jeff on Twitter @JefferyBCannon or by email: jbc165@gmail.com

References

- Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2015. “Common Fraud Schemesâ€. Accessed 2 February 2015. http://www.fbi.gov/scams-safety/fraud

- Internet Crime Complaint Center, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2013. “2013 Internet Crime Reportâ€. Accessed 2 April 2015. http://www.ic3.gov/media/annualreport/2013_IC3Report.pdf

- Robert Whitaker, 2013. “Proto-spam: Spanish prisoners and confidence gamesâ€. The Appendix, October 23, 2013. http://theappendix.net/issues/2013/10/proto-spam-spanish-prisoners-and-confidence-games

- Cormac Herley, 2012, Why do Nigerian scammers say they are from Nigeria? Proceedings of the 11th Annual Workshop on the Economics of Information Security. Berlin, Germany, 25-26 June 2012.

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020