There's always that one ultra clingy couple—you know the ones I'm talking about. The two members are practically attached at the hip, they refer to themselves as a single unit, and you honestly can't remember if you've ever seen them apart. Like two modern characters from a Shakespeare play, sometimes it seems like they would die without their significant other.

But what if that were actually true? What if two living beings had to be together or they could both die? It may sound extreme, but it happens everyday in a phenomenon known as “symbiosis.â€

Symbiosis translates from the Greek word symbiÅsis, meaning a “state of living together.†It describes a special relationship between two species. There are three main categories of symbiosis, depending on who benefits from the relationship. “Parasitism†occurs when one party benefits and the other is hurt (have you ever had that roommate who never does their dishes?). “Commensalism†occurs when one party benefits and the other is unaffected (like when you snag a friends' unwanted leftovers), and “mutualism†is seen when two species depend on one another for survival (remember our lovebirds?).

Examples of mutualism can be found across the globe from your own backyard to an exotic coral reef. The green, fuzzy lichens that you see covering trees and rocks are actually made up of two distinct organisms! A fungus provides structure for another species -either an algae or bacteria – which converts sunlight into enough food for the both of them.

These close-knit relationships are actually quite common. According to the Australian National Botanical Gardens, an estimated 80 to 90% of all plants participate in a nutrient exchange with small fungi known as “mycorrhizal fungi†that live in or on their roots. The fungi provides nitrogen or phosphorus, and the plant shares carbohydrates.

The key to these incredible natural relationships in balance. Each partnership involves two or more intimately connected species that have adapted to coexist. If that balance is disrupted, both species may fall into a perilous situation.

The key to these incredible natural relationships in balance. Each partnership involves two or more intimately connected species that have adapted to coexist. If that balance is disrupted, both species may fall into a perilous situation.

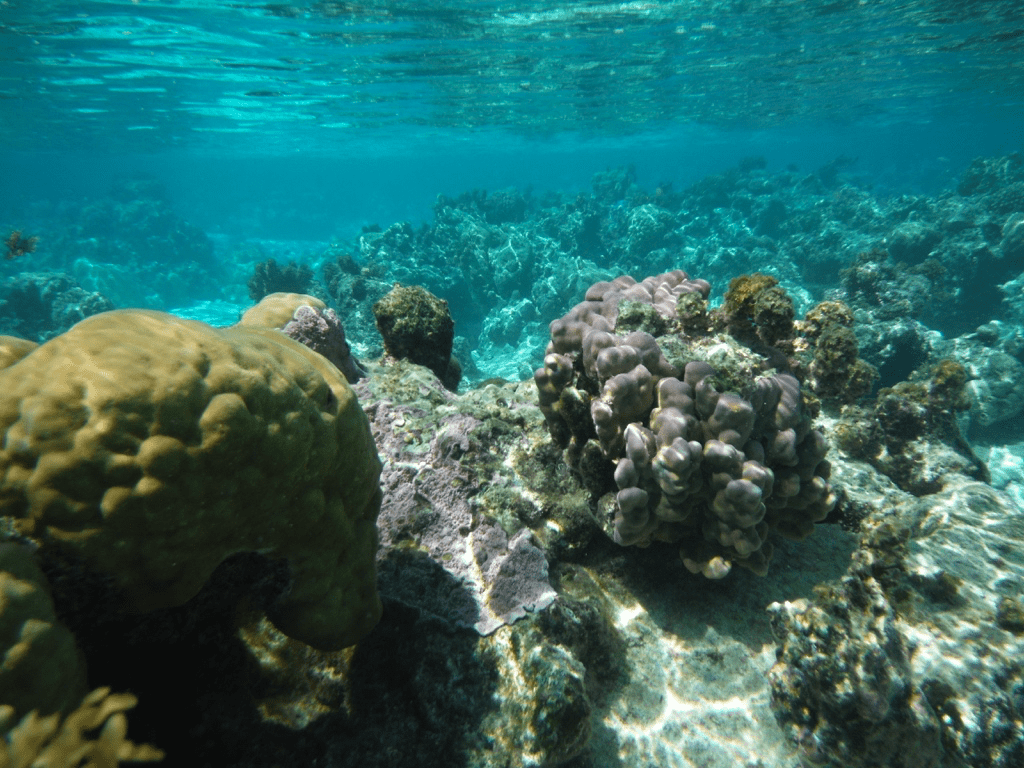

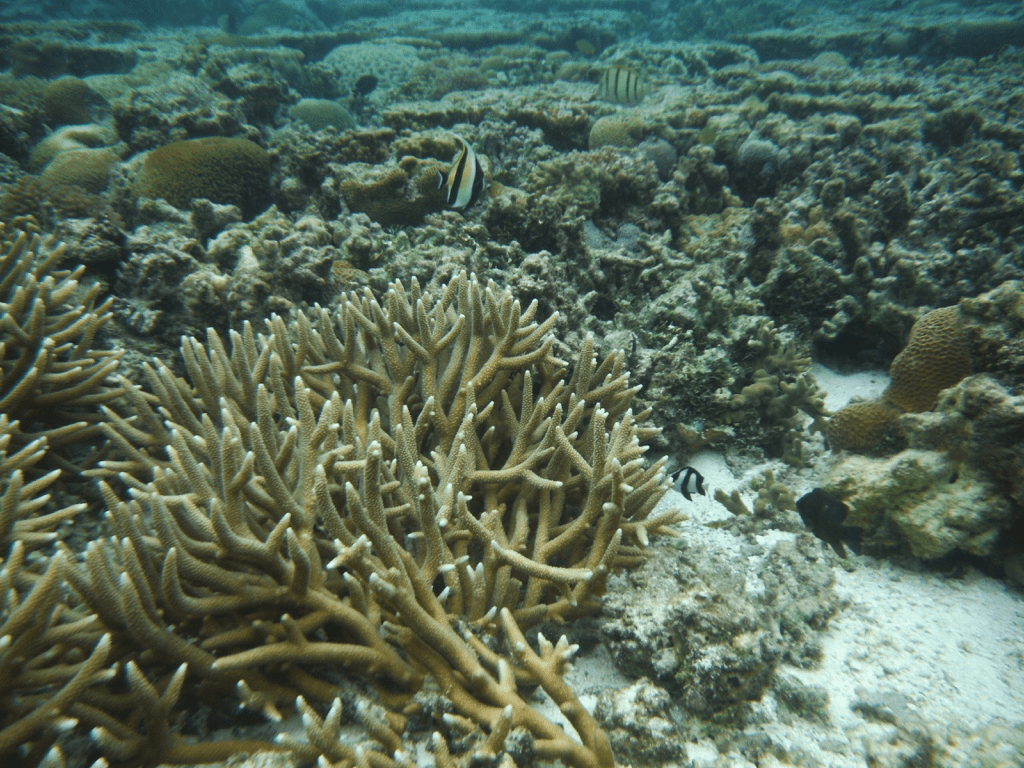

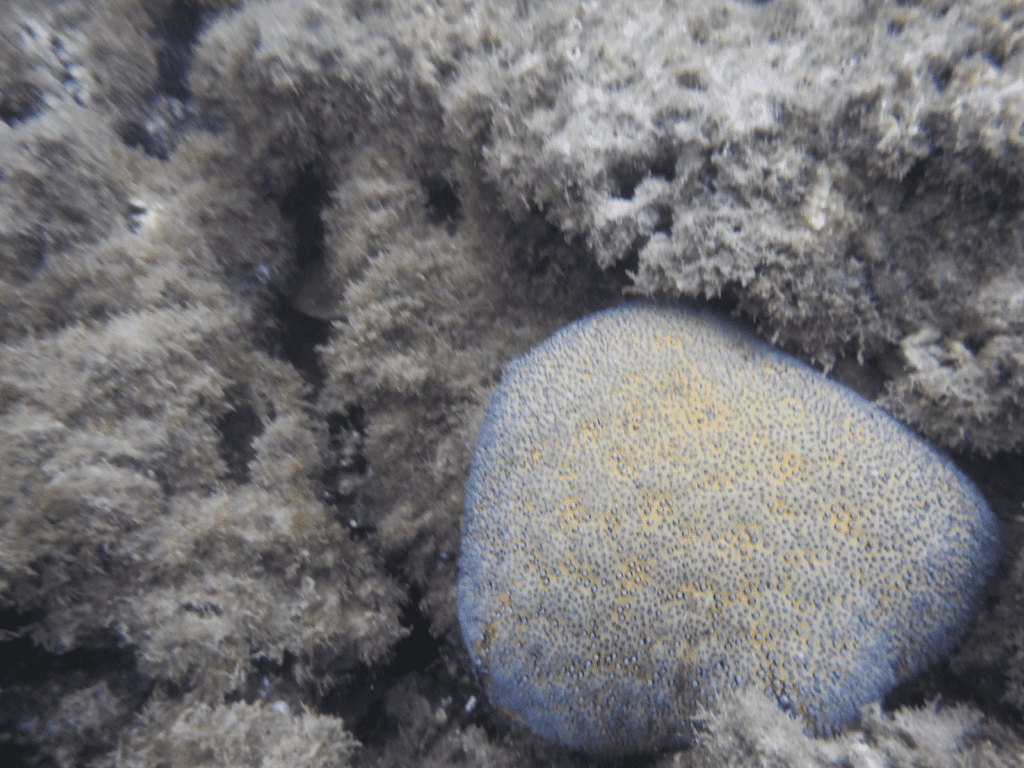

Across the world, entire underwater ecosystems are built on the foundation of intricate symbiotic relationships. Vibrant coral reefs teeming with life are actually the result of mutualism between coral polyps (animals related to jellyfish) and algae known as zooxanthellae (zo-ZAN-thel-ee, a unicellular plant).

Like the fungi in lichen, coral provides structure. The tiny polyps secrete a “skeleton†made of limestone that provides shelter for itself and its partner algae. In exchange, the algae contributes energy via photosynthesis.

Corals are termed ecosystem engineers because their expansive growth creates an environment for other organisms. Just as trees provide shelter and resources for woodland animals, coral provides habitat for fish, crustaceans, and other aquatic animals. The reefs are incredibly biodiverse: although they account for less than 1% of the ocean floor, coral reefs contain over 25% of known fish species (www.coral.org).

Reefs provide vital breeding grounds for fish that stock the world's food supply, such as snapper and coral trout. Reefs also fuel local economies through tourism and recreational activities like snorkeling and SCUBA diving. In fact, a 2004 study forecasted that growing reef tourism alone would provide $9.6 billion dollars in benefits for the U.S. annually!

The world's coral reefs are an incredible asset, and they hinge on one thing: mutualism between a tiny polyp and algae. Tragically, this relationship is easily disturbed and has been disrupted by human interference.

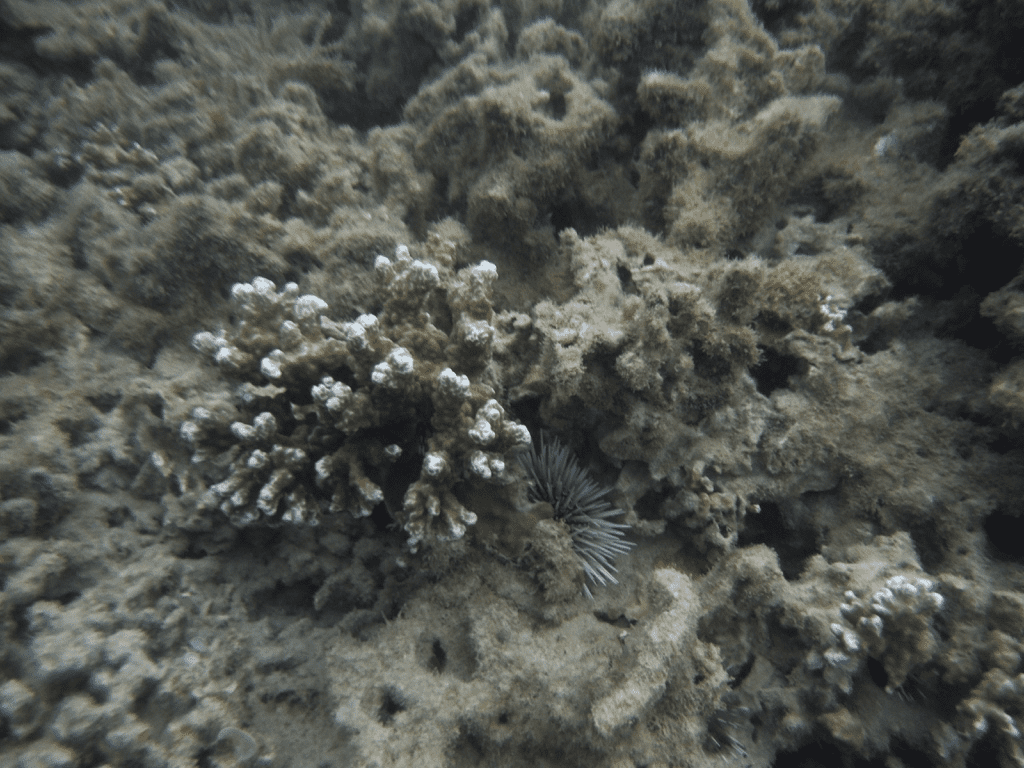

Over the past decades, coral has been exposed to fertilizer runoff, physical damage from human construction, and pollution. The largest killer by far, however, is the steady rise in ocean temperature.

Because coral thrives in a narrow temperature range, rising ocean temperatures stress the relationship between coral and algae. When the coral becomes too distressed, it expels its zooxanthellae into the water in a process known as “coral bleaching.†Without their symbiotic partner, both the coral polyp and algae will die, leaving a graveyard of white limestone skeletons. Over time, almost all the organisms that depended on the reef will relocate or perish.

27% of the world's reefs have been permanently lost, with 30% estimated to be lost by 2033. (The Economics of Coral Reef Degradation, 2003). Individuals and governments alike must work order to save this invaluable resource.

The creation of conservation zones and regulations on ocean pollution are critical to reef survival. At home, citizens can make a difference by working to reduce their carbon footprint, writing their representatives about conservation, never damaging or removing marine life from a sanctuary, and donating to conservation organizations like The Coral Reef Alliance.

Log on to www.coral.org for more information about getting involved in preserving our reefs.

Let's save our star-crossed lovers!

About the Author

|

Amanda Piehler is an undergraduate at UGA double-majoring in Biology and Science Education. When she's not adventuring in academia, you can find her dancing, running, cooking, SCUBA diving, or hiding out in a local theatre. Connect with her on Facebook or email her at apiehler@uga.edu! More from Amanda Piehler. |

References:

- All Photos by Amanda Piehler

- Dimijian, Gregory G. “Evolving Together: The Biology of Symbiosis, Part 1.â€Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 13.3 (2000): 217–226. Print. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1317043/pdf/bumc0013-0217.pdf

- Kennedy, Peter. “Decoding the Mycorrhizal Symbiosis: Why Plants Like Fungi So Much.†Mycena News. The Mycological Society of San Francisco. 56.05 (2005). http://www.mssf.org/mycena-news/pdf/0505mn.pdf

- “Oceans and Coasts- Coral Bleaching: What You Need to Know.†The Nature Conservancy. 2015. Accessed 27/07/2015. http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/urgentissues/coralreefs/coral-reefs-coral-bleaching-what-you-need-to-know.xml

- Hogan, C. Michael. “Ecology Theory: Commensalism.†The Encyclopedia of Earth. 13 December 2011. 29 July 2015. http://www.eoearth.org/view/article/171918/

- “Lichen Biology.†Fungal Biology. University of Sydney. June 2004. 29 July 2015. http://bugs.bio.usyd.edu.au/learning/resources/Mycology/Plant_Interactions/Lichen/lichenBiology.shtml

- Lepp, Heino. “Micorrhizas.†Australian National Botanical Gardens and Australian National Herbarium, Canberra. 2012. 29 July 2015. http://www.cpbr.gov.au/fungi/mycorrhiza.html

- Bledzki, Leszek. “Ecosystem Engineer.†The Encyclopedia of Earth. 1 March 2010. 30 July 2015. http://www.eoearth.org/view/article/152253/

- Coral Reef Alliance. 2014. Web. 30 July 2015. www.coral.org

- “Community Power ‘can rescue failing fish stocks.'†Current Biology. 1 April 2013. Web. 30 July 2015. http://phys.org/news/2013-04-power-fish-stocks.html

- Cesar, Burke, Pet-Soede. “The Economics of Coral Reef Degradation.†Cesar Environmental Economics Consulting. February 2003. Web. 30 July 2015. http://www.icran.org/pdf/cesardegradationreport.pdf

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020