For decades millions of visitors wound their way underneath the towering skeletons of Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops at Washington, D.C.'s Museum of Natural History. Now, the National Fossil Hall has closed as curators work on a revamped exhibition, tentatively titled “Deep Time,†set to open in 2019. Alongside the dinosaur skeletons that have long dominated the museum as they once dominated the planet, this new exhibit, will include an Anthropocene section with a distinct focus on a species much smaller physically than the surrounding dinosaurs, but which has also had a dominant impact on the planet—humans.

This exhibit is just one example of the recent prevalence of a relatively new concept—the Anthropocene, also known as the “Age of Humans.†As environmental scientists continue to document the magnitude of human impact on the earth, many generally agree that sometime in the last 10,000 years—though when is still under debate—humans have changed the geology of the planet on par with other geological changes like meteor strikes, ice ages, and volcanic eruptions. These are the types of impacts that have signaled divides in geologic epochs for the last 4.5 billion years. But for other scientists—especially geologists—the debate does not center around when the Anthropocene epoch began, but if it has begun at all.

Typically, stratigraphy—the information that geologists pull from ice cores, rock layers, ocean sediments, and other “stratified†or layered geologic deposits under Earth's surface—has been the sole determinate of geologic time. To determine divisions in Earth's history, scientists look for changes in stratigraphy that occur more or less simultaneously everywhere on Earth. For instance, the transition to the Holocene is marked by debris and scouring marks left by glaciers as they retreated after the last Ice Age. Marking a distinction between the Holocene and the Anthropocene, means that we believe that, even if humans disappeared from the planet tomorrow, our presence could still be seen hundreds of thousands or even millions of years from now in earth's geologic strata.

Some stratigraphers argue that marking a change to the Anthropocene is more of a political statement on the large-scale nature of human environmental impacts than a true stratigraphic change and that it could take centuries before we can truly determine the lasting impact humanity has had on Earth's stratigraphy.

![Current Geologic Time Scale, By United States Geological Survey [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://www.athensscienceobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/image001.jpg?w=148)

Currently, in the official Geologic Time Scale, earth has been in the Cenozoic era for approximately 66 million years since the extinction of the dinosaurs. Within this era, the Quaternary Period makes up the last 2.58 million years and consists of the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs. At the end of the Pleistocene epoch approximately 12,000 years ago, the Earth warmed, the glaciers retreated, cold-adapted animals like the wooly mammoth died off, and earth entered the Holocene epoch. This latest transition, however, first proposed in the 1860s and endorsed by the U.S. Commission on Stratigraphic Nomenclature in the 1960s, was only formally accepted in 2008 by the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), the same group that is now faced with determining the fate of the Anthropocene.

Even for those scientists who agree that we are now in the Anthropocene epoch, choosing an official end date for the Holocene has been fiercely debated. For some, the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the late 1700s may be that magic date. In the just over 200 years since then, humans have increased the amount of methane in the atmosphere by 100% and carbon dioxide by 30% as well as produced a hole in the ozone layer. Arctic ice continues to melt; species are dying out; the ocean is acidifying; and agriculture and mining are stripping sediments from the earth much faster than natural processes—all of this due to human activities.

Other researchers have fought for the Anthropocene to begin thousands of years earlier to coincide with agricultural expansion around 5,000 years ago or with increases in mining that began 3,000 years ago. Neither of these changes nor those seen around the turn of the 19th century, however, appear to have produced clear global markers in the geologic record on par with past delineations.

But other more recent dates have also been proposed. In an article published in Nature this past March, two geographers argue that the Anthropocene begins with the reforestation of millions of acres of agricultural land after European diseases killed over 50 million Native Americans. This resulted in a drop in atmospheric CO2 that can be seen in ice cores across the globe formed between 1570 and 1620. Another study published in March in Environmental Science & Technology, proposes 1950 as the start date when a layer of fly ash, or soot—by-products of burning coal and oil—appears in soil cores worldwide.

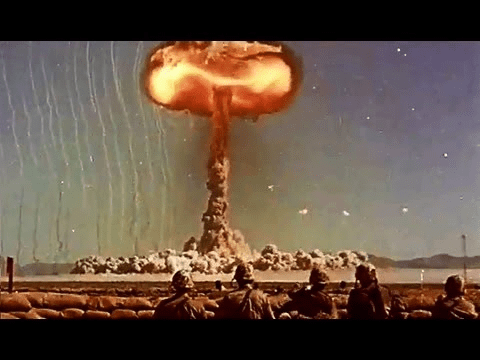

One date, however, has gained more traction within the ICS working group than the rest—the atomic age. Beginning in 1945 and lasting until 1963, countries around the world conducted over 500 nuclear test blasts, which sent debris around the globe and created a sediment layer filled with radioactive elements. Around this same time, plastics, artificial fertilizers, and leaded petroleum began being used on a much larger scale worldwide and, as such, also began leaving indelible marks in the earth's sediments. With that in mind, earlier this year, the ICS group tentatively proposed July 16, 1945—the date of the first atomic-bomb blast—as the beginning of the Anthropocene. The group will not make their formal recommendation of whether to add the Anthropocene to the official Geological Time Scale as a defined geological unit, however, until 2016.

Regardless, the Anthropocene has already become a pervasive presence in both academic and popular culture. Three Anthropocene-based academic journals have sprung up in the last couple of years and peer-reviewed papers on the topic have risen dramatically in that same time period. A 2011 magazine cover from The Economist proclaimed, “Welcome to the Anthropocene†and in 2014 the American Association for the Advancement of Science opened an art exhibit, “Fossils of the Anthropocene,†to portray humanity “through the lens of the artifacts that we might leave behind.â€

But, perhaps, increasing human recognition of the extent of our impact on Planet Earth is the real goal behind the push to formalize the Anthropocene. According to Rick Potts, the Director of the Human Origins Program at the National Museum of Natural History, “The Anthropocene as a way of thinking about the world is more important … than [its] status as a new geologic era. It is the awareness that humans are active players in the geological and biological processes of the Earth.â€

About the Author

Anne Chesky Smith is a doctoral student in the University of Georgia's Integrative Conservation and Anthropology program. When not researching land use in southern Appalachia, Anne can be found bumming around the horse barn, trying to click at the same time as everyone else in her adult tap class, or napping with a good book in her (indoor!) hammock. You can hear more from Anne or get in touch with her at annecheskysmith.wordpress.com. Anne Chesky Smith is a doctoral student in the University of Georgia's Integrative Conservation and Anthropology program. When not researching land use in southern Appalachia, Anne can be found bumming around the horse barn, trying to click at the same time as everyone else in her adult tap class, or napping with a good book in her (indoor!) hammock. You can hear more from Anne or get in touch with her at annecheskysmith.wordpress.com. |