Farmers today face a number of challenges, old and new. Global climate change is exacerbating harsh growing conditions, invasive species are devastating crops, and consumer demands are shifting toward sustainable farming practices. Farmers also have to balance the increasing cost of fertilizers and pesticides with a need for high crop yield. An estimated 877 million pounds of pesticides were used in 2007, with corn, potatoes, and wheat comprising two-thirds of total pesticide use.

To help these farmers, researchers in Ireland and Denmark are exploring ways to use a well-established, yet recently defined symbiosis to address the challenges associated with applying chemical pesticides in cereal grains – domesticated grasses like wheat, rice, barley, and rye.

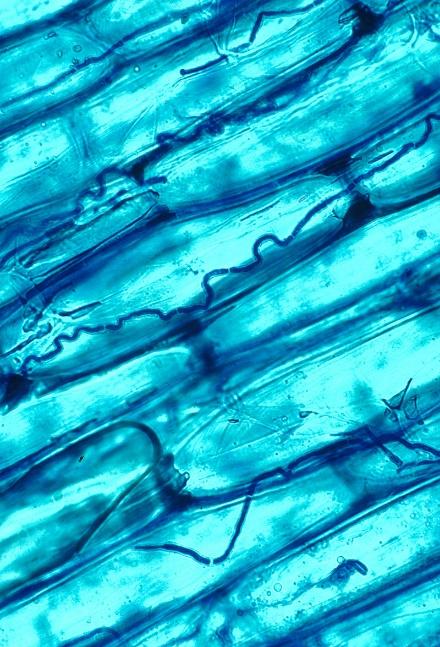

Many plants have beneficial microbes associated with them, with the most well-known being mycorrhizae, microscopic fungi that colonize roots of approximately 80% of plant species and help the host plant take up nutrients from the soil. The relationship between plants and fungi likely started when plants colonized land, and recent research suggests that the ancestors of land plants were predisposed for endosymbiosis with microorganisms that made nutrients available to their roots.

The relationship between grasses and beneficial fungi has been studied extensively, and is referred to as a defensive mutualism, where endophytic fungi live their entire life inside of plants and have no negative effect on the host plant. Additionally, the fungi can help plants overcome environmental stressors such as drought, high soil salinity, and nutrient availability. Ergots, act as a natural pesticide, and are produced and secreted by fungal endophytes Alkaloids, another chemical produced by fungal endophytes, leak into the soil and may even act as signals to nearby beneficial bacteria, recruiting them to the roots of the host plant to help protect against disease. These chemicals, and the bacteria they recruit, can prevent plant disease by breaking down potential pathogens or producing antibiotics. This is great for the plant, because it doesn't have to initiate an immune response when pathogens are trying to invade. The microbes act like mercenaries and do all the fighting for the plant.

The fungi also benefit from this relationship. The plant provides food (sugars made from photosynthesis) and a home for the fungus. By living inside the plant tissue, the fungus is protected from harmful Ultraviolet (UV) radiation and dehydration. In short, the healthier the plant, the larger it grows, resulting in more room for the fungi to live and reproduce. Researchers believe that by taking advantage of this unique partnership, these fungi can be used as alternatives to fertilizers and pesticides in conventional agricultural practices.

It could be possible to curb the future use of applied pesticides and improve food security by taking advantage of the many benefits of plant-fungi symbiosis. To prove this, researchers grew plants from seeds that were given fungal endophytes and then infected them with pathogens. They found that the introduction of certain endophytes slowed or stopped the progression of take-all disease, which affects barley, wheat, and rye. These crops are economically and nutritionally important worldwide, and take-all disease is a major pathogen that can result in significant losses for farmers. Using fungal endophytes to prevent disease could potentially reduce the amount of fungicides used by farmers, saving money and lessening the environmental impact of conventional farming practices.

The researchers also found that introducing the endophytes helped the plants use less water, helping them to survive drought and nutrient stress. These added benefits to the host plant support the use of beneficial fungi in agriculture. Fungal endophytes could provide a more cost effective, accessible, and sustainable method for a growing and developing world population. With all of the benefits fungi have to offer, they may be the solution modern agriculture has been looking for.

About the Author

Aileen Ferraro is a PhD graduate student and fungal enthusiast in the Department of Microbiology at the University of Georgia. Her background is in microbial ecology, focusing on the relationship between plants, fungi, and bacteria. When she's not in the lab, Aileen can be found baking breads with home grown yeast cultures, exploring the Georgia wilderness, or enjoying a pint on a patio. More from Aileen Ferraro. Aileen Ferraro is a PhD graduate student and fungal enthusiast in the Department of Microbiology at the University of Georgia. Her background is in microbial ecology, focusing on the relationship between plants, fungi, and bacteria. When she's not in the lab, Aileen can be found baking breads with home grown yeast cultures, exploring the Georgia wilderness, or enjoying a pint on a patio. More from Aileen Ferraro. |