Are we a product of our environment or bound to a predetermined fate dictated by our genes? To answer the age old nature versus nurture dilemma, both. It is widely known that the environment can alter our DNA sequence through genetic mutations as a consequence of external factors such as toxins and carcinogens. However, our environment also affects the expression of DNA.

But the distinction between a DNA sequence and its expression initially may seem minute. So how can DNA be expressed differently without any alterations to the genome? Take for example the two different renditions of Romeo and Juliet, the 1996 version directed by Baz Luhrmann and the 1936 version directed by George Cukor. Both movies have the same script (courtesy of Shakespeare), however the tragic story of the two star-crossed lovers is conveyed in varying manners. The former is a musical graced with the presence of Leonardo DiCaprio, while the latter was produced 60 years earlier, is in black and white, and has a distinct and disappointing lack of Leonardo DiCaprio. Similarly, while the DNA sequence or “script†may remain constant, it can be presented and expressed in different ways.

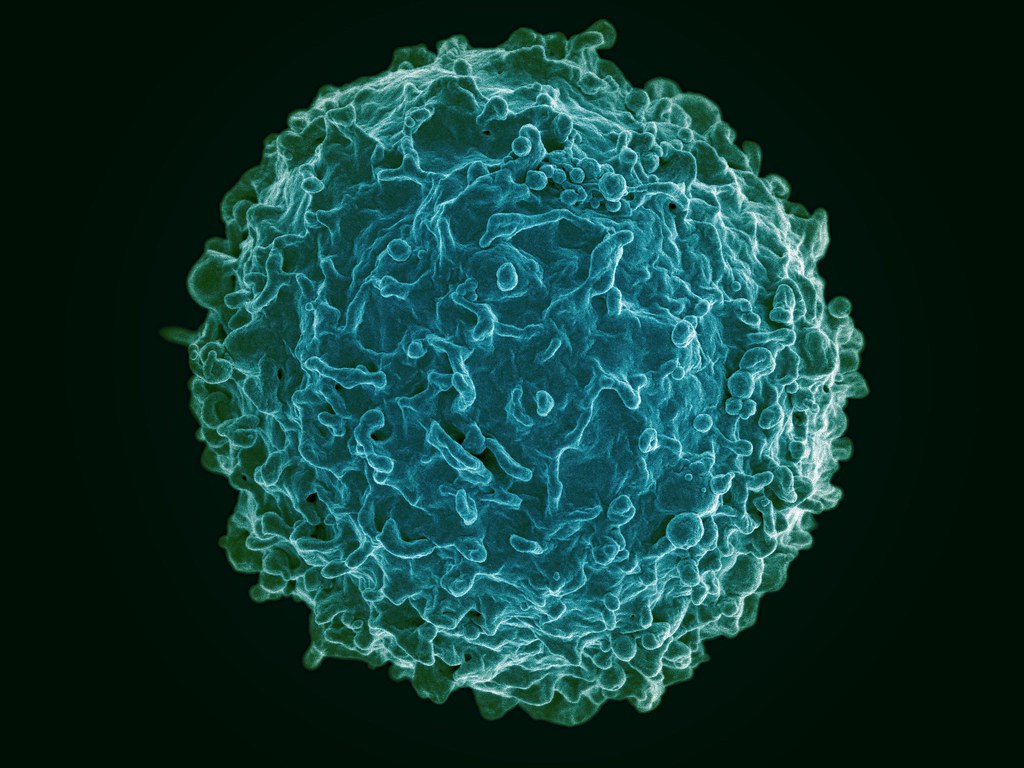

Epigenetics works in much the same way. Basically epigenetics is a set of chemical modifications that attaches to our genes and tells them when to switch on or off. This mechanism does not alter the genes themselves, but alters their expression. One epigenetic process that manipulates how DNA is interpreted is called histone modification in which DNA is conveniently packaged by molecular “spools†called histones. When DNA is tightly wound around these histones, it cannot be read, and is therefore not expressed. We are incredibly vulnerable to epigenetic changes through mechanisms such as histone modification during gestation.

A notable example of histone modification and the profound effects that diet has on the expression of certain genes is best examined through the Dutch Hunger Winter (1944-1945) during WWII. This initially well fed population experienced a short period of intense hunger that abruptly ended, creating unique circumstances which help exemplify the effects of malnutrition on the different stages of pregnancy. If the women were in their first 10 weeks of pregnancy when the famine occurred, their babies generally had normal birth weights but higher obesity rates later in life. If the mothers were near the end of their pregnancies when the famine occurred, their babies were generally born with lower birth weights and stayed small throughout their lifetimes. Audrey Hepburn was one such example who was born during the onset of the Dutch Hunger Winter and who stayed small throughout her life.

The timing of the famine during gestation has significant effects upon the programming of adult diseases which indicates that something more than just genetics is at play affecting individuals later in life. Both groups of people had the same access to food as adults, yet there are significant discrepancies in their ability to process insulin. This is a result of an increased expression of the insulin growth factor gene 2 (IGF2) in individuals born during the onset of the famine. The increased expression of IGF2 is a result of epigenetic mechanisms called DNA methylation and histone modification. This caused the individuals born during the beginning of the famine to stay small throughout their life as well as higher incidences of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases later in life.

Additionally, the effects of the famine did not just impact one generation. Studies have shown the transgenerational effects associated with stresses during gestation are controlled by a collection of genes called MOTEK genes (Modified Transgenerational Epigenetic Kinetics) which are responsible for turning on and off epigenetic transmissions across generations. It was found that grandmaternal exposure to famine increased the risk of adiposity in babies and chronic health problems later in life.

Another modern example of histone modification and DNA methylation can be seen in individuals suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after the 9/11 attacks. One study showed that maternal PTSD is linked to lower salivary levels of cortisol, a stress hormone, in adults whose mothers experienced PTSD during their pregnancy. They found that significant stresses during gestation (such as PTSD) can cause epigenetic modifications in certain risk alleles such as the FKBP5 gene. A decreased expression of the FKBP5 gene through increased DNA methylation is associated with lower cortisol levels.Therefore, offspring whose mothers experienced PTSD during pregnancy were more prone to lower cortisol levels as adults. This phenotype is due to a decreased expression of the FKBP5 gene.

Epigenetics teaches us that the power our genome is not set in stone. Instead it has the potential to be altered in a single person's lifetime and can even have significant effects over multiple generations. Within each one of us is a reserve of genetic memories both from our ancestors and collected over our own lifetime. So next time you're trying to convince yourself to go for a run, remember- don't just do it for you, do it for your grandkids.

About the Author

Gazal Arora is an undergraduate Cellular Biology major at the University of Georgia. When she's not studying at the Science Library, she can be found hiking, reading, or Snellibrating. For more information you can email her at ga25144@uga.edu or follow her on Twitter: @gazalarora_. Gazal Arora is an undergraduate Cellular Biology major at the University of Georgia. When she's not studying at the Science Library, she can be found hiking, reading, or Snellibrating. For more information you can email her at ga25144@uga.edu or follow her on Twitter: @gazalarora_.

|

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020