In October 1997, the Sci-Fi drama Gattaca was released on the big screen in the United States. The film takes place in a dystopian future where genetically-engineered humans are superior to unaltered ones. Its protagonist, Ethan Hawk, is born as an “invalid†(someone without genetic engineering) and has to assume the identity of a “valid†(someone with genetic advantage) to achieve his life-long dream of becoming an astronaut.

At the time when it was released, the future proposed by Gattaca seemed distant, dramatic, and frankly, pretty unlikely. As the understanding of the human genome evolved over the next several decades, however, manipulating genetic traits in humans became all too real.

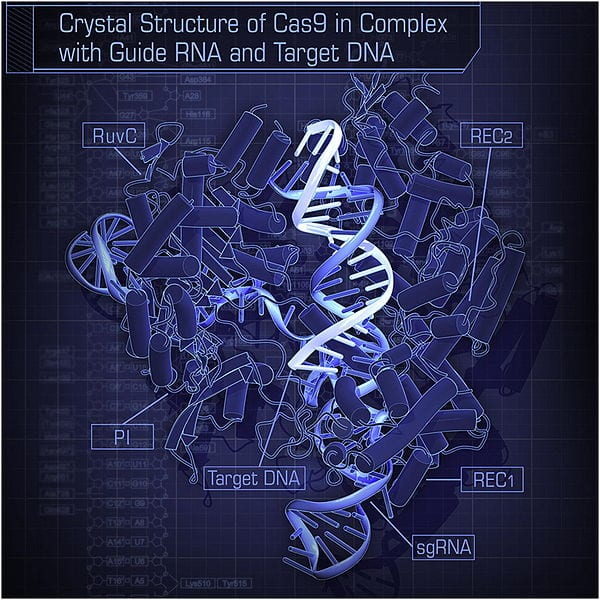

In particular, the discovery of the CRISPR/Cas9 system of DNA alteration in 2013 revealed a cheap, relatively simple way of altering the human genome (you can read a previous article written by Anna Lau giving a brief explanation of the CRISPR/Cas9 system here). Essentially, CRISPR/Cas9 is an efficient system that can be designed to recognize and cut any sequence of DNA with extreme specificity. The cell is then prompted to repair the damage, which can involve the swapping of an alternative copy of that region with one introduced artificially.

Initially researchers were overwhelmed and excited with the possibilities this new technology provided. Researchers were conducting tests for human disease on model species like mice and monkeys, attempting to discover “cures†to genetic disorders like HIV, Alzheimer's, and even cancer.

When an article was published outlining the use of CRISPR/Cas9 editing on human embryos in May 2015, the scientific community wanted to take a step back. The altering of embryonic cells raised an important ethical concern: should this technology be used to intentionally alter a developing human baby?

One of the creators of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, microbiologist Jennifer Doudna of the Univeristy of California Berkely, called for a “global pause in any clinical application of the CRISPR technology in human embryos to […] consider all of the various implications of doing so.†Many other public/private organizations followed Doudna's lead and advised their constituents to halt any further research on human embryos.

In December of 2015, an international group of scientists were able to come together and further discuss this issue at length. The meeting was organized by the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, The Institute of Medicine, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Royal Society of London. Their main aim in this meeting was outlined by Dr. David Baltimore: “…When, if ever, we will want to use gene editing to change human inheritance.â€

So when will scientists be ready to alter human inheritance? The consensus reached at the international meeting was simple: not yet.

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has yet to be perfected in model species and humans, a complete understanding of genetic human traits and diseases has yet to be reached, and ethical standards have yet to be outlined by governing bodies.

For now, all of us “invalids†can rest easy. The world of genetically engineering human embryos and designer babies is distant. But remember: distant may be sooner than you think.

About the Author

Ellen Krall is an undergraduate at UGA studying Plant Biology. When she's not in classes or at the lab, she enjoys long walks in the State Botanical Garden, being kind of good at several instruments (violin, ukulele, banjo), and naming her Beta fish after famous scientists. Ellen Krall is an undergraduate at UGA studying Plant Biology. When she's not in classes or at the lab, she enjoys long walks in the State Botanical Garden, being kind of good at several instruments (violin, ukulele, banjo), and naming her Beta fish after famous scientists. |

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020