Some of the most powerful things are quite small: a microscopic virus can defeat an elephant; Giant Redwoods grow from tiny seeds; a computer chip the size of your fingernail can send us to Jupiter and back; and just one minuscule sperm cell can fertilize an egg and start new life.

In most animals, sperm are pared down to the bare minimum. They are small cells that males make lots of with little investment on their behalf. In humans, one male ejaculation can have close to 100 million sperm. Evolutionarily, this type of sperm makes sense. The smaller sperm are, the “cheaper†they are to produce, enabling a male to have lots of offspring and ensure his genes continue on to the next generation. So when it comes to sperm, smaller is usually better– unless you're a fruit fly, that is.

The fruit fly Drosophila bifurca is small in size, but mighty in giant sperm. These fruit flies have the biggest sperm relative to body size than any other animal that we know of.

So, why do these little fruit flies have sperm that break all the rules?

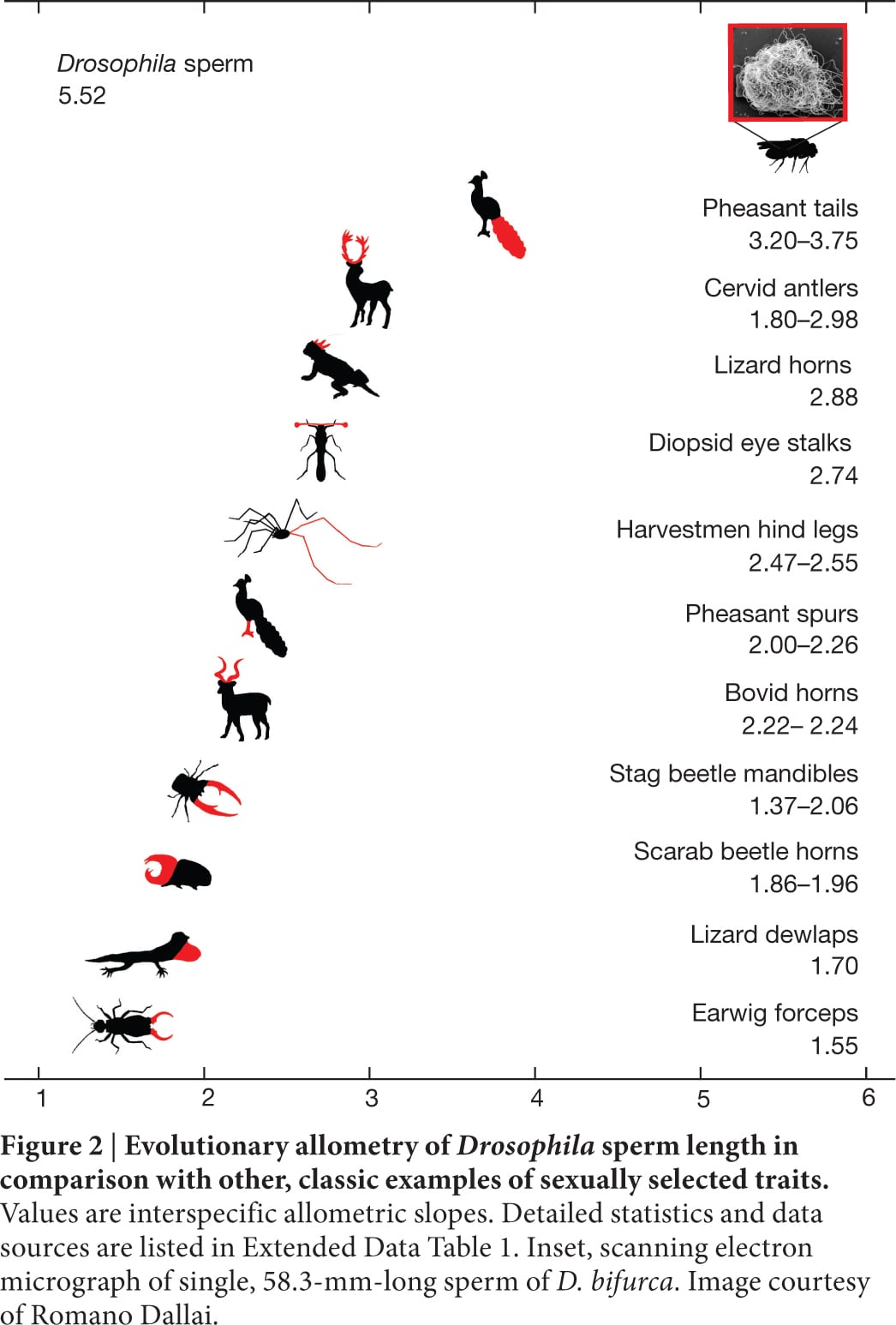

To answer this question, perhaps we need to change the way we think about sperm. What if these sperm serve another purpose beyond just being a tool to get the job done; but are also used to show off? Scientist Scott Pitnick views fruit fly sperm more as sexual ornaments (flashy traits), like a deer's antlers or a peacock's tail.

Having such large flashy traits takes a lot of energy; because of this, only the healthiest of males can afford to produce such features. These flashy traits are like a big light-up billboard to the females saying, “I'm healthy and can make lots of babies, pick me!â€.

While huge antlers and beautiful feathers are quite attractive, these outrageous sexual ornaments pale in comparison to the fruit fly's sperm. For example, an antelope's horns will grow twice as fast as its body does, a peacock's tail three times as fast; but the fruit fly's sperm grows 5.5 times faster than its body.

Not only that, these sperm are ~ 20 times the length of the fly's body. In order to fit such large sperm into a small fly, these sperm wrap up like a giant ball of yarn!

When a female picks the deer with the fanciest antlers, the peacock with the most ornate tail, or the fly with the biggest sperm — she's also picking one of the best, healthiest males to mate with. For a male fruit fly, bigger sperm means more success with the ladies.

But, unlike tails and horns, sperm aren't visible. So, how would a female know this?

Well, she might not know directly. But here's the thing: female fruit flies often mate with multiple males. While inside the female, sperm jostle around to try and win over fertilization rights. Bigger sperm are better competitors and it is here that they often out compete smaller sperm.

The higher the competition between males, the more complex these sexual ornaments can become.

Scott Pitnick calls this the “Big Sperm Paradoxâ€, meaning that having giant sperm is both an extreme benefit and weakness. Is making huge, energetically costly sperm worth the uncertainty of fertilization?

To put some clarity on this paradox, we need to shift our focus to what the females are doing.

Female fruit flies store sperm in a storage unit called the seminal receptacle. This is where she holds sperm until her eggs are ready to be fertilized. Now, of course this storage unit is not infinite, it has limits–therefore females want to house only the best of the best.

Therefore, generations of females have evolved longer seminal receptacles to gain the capacity to store larger sperm, and thus ensuring they get the best sperm possible (cue all the light bulbs)!

By having evolved a longer seminal receptacle, females drive more competition in males by selecting for the longest sperm, which comes from the best males.

This creates a positive genetic correlation between sperm and the female’s storage unit; the large size of both these parts drives the evolution of the other.

While you might not see it, male fruit flies are in a secret sex war. So give those little fruit flies some credit! Sometimes big things do come in small packages!

Amanda Shaver is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Genetics at the University of Georgia. She enjoys dancing, crafting, and playing with her dog Mr. Peabody. High on her list of accomplishments is eating a whole block of cheddar cheese in one sitting without negative consequences. Amanda currently serves a Associate Editor-in-Chief for the Athens Science Observer and is on the Athens Science Cafe Programming Board. You can email her at Amanda.shaver@uga.edu or follow her on Twitter @AOShaver. More from Amanda Shaver. Amanda Shaver is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Genetics at the University of Georgia. She enjoys dancing, crafting, and playing with her dog Mr. Peabody. High on her list of accomplishments is eating a whole block of cheddar cheese in one sitting without negative consequences. Amanda currently serves a Associate Editor-in-Chief for the Athens Science Observer and is on the Athens Science Cafe Programming Board. You can email her at Amanda.shaver@uga.edu or follow her on Twitter @AOShaver. More from Amanda Shaver. |