“The body remembers. Stuffed until an event, a sound, a sight, a touch, a word, or a person awakens themâ€. The body remembers pain, domestic abuse, and the horrors of war. Unfortunately these memories become a burden on a person's mind and body. This debilitating and stressful illness is commonly known as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD for short. Victims of PTSD, specifically veterans, can go through various means of therapy, like traditional one-on-one therapy and group therapy. However, these methods don't always work. A lot of feelings and memories stay bottled up, preventing the victim from healing. But now, it seems as though virtual reality provides the sound, sight, or word that “awakens†what the body has gone through.

A major problem in getting PTSD patients to talk about their experiences is that they block out many memories as a coping mechanism. They disassociate themselves from their own bodies, remembering themselves in something resembling a third-person view. Forming memories based on this third person view is not a very effective way for the brain to store information, which is why victims of PTSD do not remember what they went through in detail most of the time.

This is where virtual reality comes in. Dr. Henrik Ehrsson of Sweden's Harolinska Institute believes that those “out of body†memories may be stored in a different part of the brain, which is why he is trying to recreate those people's memories in order to treat them. Maybe, “by reinstating the out-of-body illusion, we would be able to help people with PTSD remember the event in a normal wayâ€, says Dr. Ehrsson.

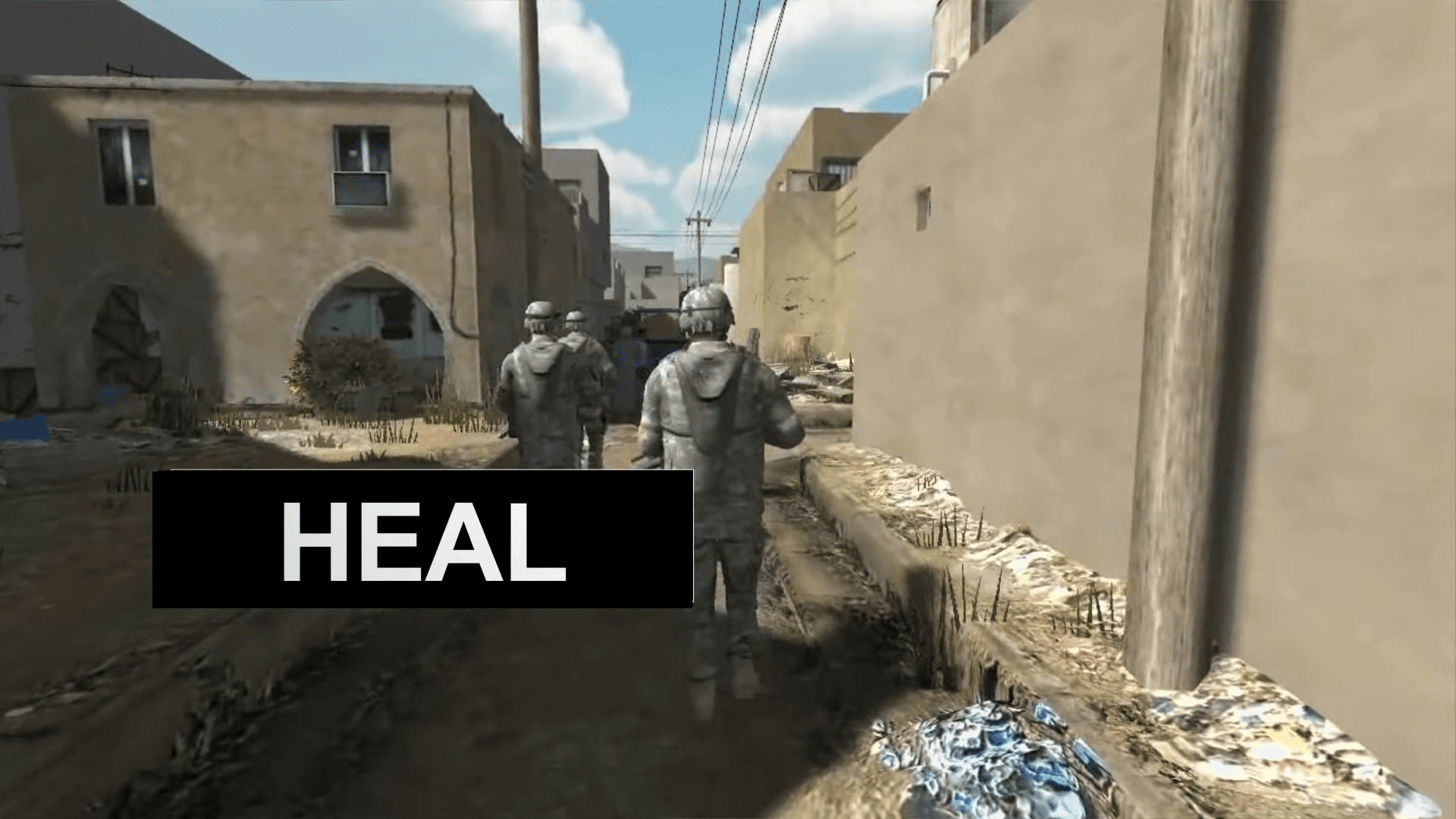

One common method of treatment used in virtual reality is “exposure therapyâ€. This is also used in clinical psychology where they recount their trauma and visualize it. By repeatedly confronting this trauma, the brain can reduce its anxiety in response to those memories. This is also used in traditional “talk therapy,†however younger military personnel who grew up with digital gaming technology are more open to using virtual reality treatment than older veterans.

Dr. Skip Rizzo, a clinical psychologist at the University of Southern California Institute of Creative Technologies, has already created 14 virtual “worlds†for patients. In fact, the technology is designed in such a way as to allow clinicians to add custom elements according to their patient's needs, like helicopters and missiles. But there is no need to get too focused on the details of the game: the brain fills in the blanks anyway. From a cognitive view, the player will know that nothing is there, but both consciously and unconsciously, they respond as if there is. A patient will talk through it to the clinician who is listening along and feel like they are physically there, unlocking memories and working through their trauma.

The virtual reality environment trains the patient in stress resilience and management, showing them how to regulate their emotions when confronted with their memories or triggers. Essentially, virtual reality teaches them valuable coping tools with each session. During a session, the patient wears a virtual reality headset and can either walk on a platform, controlling themselves in the game, or control themselves through a video game control. They can even have a fake gun. The virtual reality is experienced in first person. The psychiatrist can watch what the patient is seeing on a large screen and talk them through the experience as well as listen to the patient describing what they went through.

Virtual reality treatment is still in its infancy, but it holds a lot of promise. It may seem counterintuitive to place war veterans in places similar to their source of trauma, but this technology gets many people to open up and start working through their trauma when they never had before. Through the sessions they are forced to remember and face their fears, learning coping mechanisms in a safe, controlled environment with a trained professional.

To see the virtual reality technology in action, check out this short documentary by VICE.

About the Author

Ana Mandujano is an undergraduate student in the School of Public and International Affairs studying International Relations and pre-medicine. When she's not studying for organic chemistry and strategic intelligence, she's a Spanish interpreter for Mercy Clinic and ruining movies for everyone by pointing out historical inaccuracies. More from Ana Mandujano. |

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020