Mohammed Hafizur Rahmen is a Bangladeshi eggplant farmer who owns a single acre north of the country's capital Dhaka. Until recently, he spent two days a week every growing season spraying his crops with a toxic pesticide to ward off the “fruit and shoot borerâ€, a caterpillar-like pest that decimates crops throughout Asia. Despite frequent use of the expensive sprays, Mohammed still lost over half of his crops to the persistent creatures and was left with little money to support his family.

Then, along came a magical new vegetable! A pest-resistant strain of eggplant (developed by the Indian seed company Mahyco) was introduced to a group of farmers in Bangladesh. Mohammed was one of the first to grow the new crop, and when he did, his yields doubled! He could harvest and sell the brinjal (eggplant's name in Bangladesh) multiple times per growing season with no use of pesticides.

It seemed like a happy ending. There was a problem with pests, so a pest-resistant form of brinjal was developed to help struggling farmers like Mohammed thrive. The end, right? Not quite.

The Controversy in Bangladesh: what does science say?

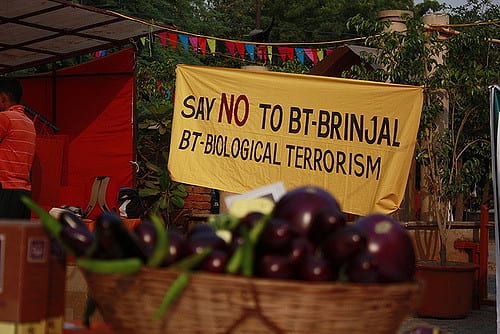

A controversy began to surround this new form of eggplant because it is not a naturally derived strain; it is a genetically modified (GM) crop developed by scientists. The new variety, called “Bt Brinjal,†has an additional inserted gene that originates from the organism Bacillus thuringiensis, a soil dwelling bacteria with a natural mechanism that repels and kills the “fruit and shoot borer.â€

The bacterial gene produces an insect toxin that is expressed in all parts of the crop. When an insect eats the crop, the toxin enters their gut and binds to receptors there. After binding, the toxin causes holes to form in the intestinal tract where bacteria from the body (and other sources) can enter. Within hours, the insect will stop feeding on the plants and die due to microbial related illnesses. This toxin can only bind to receptors in insect guts, not mammal guts, making the crop safe for human consumption.

Scientists involved with Bt brinjal were in agreement; Bt brinjal was safe to eat and effective in repelling insects. The Mahyco scientists that developed Bt brinjal found that it did not cause any notable changes in their toxicity study on animals, and the EPA also concluded that the Bt insect toxin likely has no long-term effects on humans.

Better yet, after the first growing season in Bangladesh, Dr. Rafiqul Monal of the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute announced that, “the performance of Bt brinjal was better than non-Bt in all regions.â€

What does the popular media say?

However, some green activists were still concerned with the safety of these crops and began to investigate field trials in Bangladesh themselves. Journalists for the United News of Bangladesh (UNB) reported that they visited several of the farmers (including Mohammed Rahmen) who were given Bt brinjal, and found many plants dead or dying. They also spoke to the farmers, and reported they were disappointed with the performance of the new variety. This report was bolstered by another article written by popular anti-GMO activist Mae-Wan Ho, that warned Bt brinjal varieties were dying prematurely due to a new, unknown disease.

Supposedly both sides were looking at the same crops and talking to the same farmers, so how is it that completely opposite conclusions were reached?

What may have caused this miscommunication?

Members from Cornell and the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute followed up in person with the farmers mentioned in the original UNB article in an attempt to get to the bottom of the controversy. While visiting the farms, it was evident that some farmers' brinjal crops were experiencing bacterial wilt, a disease that even affects Bt brinjal. So the media reports were somewhat correct: some plants had died from a disease. However, this was not a new disease, and its presence was unrelated to Bt brinjal.

Another possible explanation for the discrepancy is that the reporters misinterpreted field studies and the nature of the brinjal plant itself. In the Bt-brinjal fields, scientists planted “control†plants (that are not pest-resistant) alongside the new resistant varieties to serve as a comparison point. Without knowing this, it would be easy to look at a trial field and conclude that a huge portion of the plants are dying.

Journalists also visited farmers late in the growing season when brinjal plants die due to their life cycle. Brinjal plants flower, produce eggplants, and die all in one season, no matter what variety. Again, without knowing this, reporters most likely assumed it was the failing Bt crop.

Mohammed Rahmen himself issued a statement to clarify the report made by UNB and also commented on his overall opinion of Bt brinjal. He told BBC that, “In the last 10 years, the amount of yield I received last year, I never received such yield all my life and neither did my neighbors,†he said. “That is why my neighbors are inspired and me, too.”

The Controversy Internationally

The controversy and miscommunication surrounding Bt brinjal is representative of what is happening across the globe. Thirty-eight countries have banned all GMOs, and India has placed a moratorium on the commercial release of Bt brinjal itself. Largely, these political decisions are fueled by the fear that the general public has about GMOs. In a survey conducted by the Pew Research center, fifty-seven percent of the general public thinks that GM foods are unsafe to eat while eighty-eight percent of scientists say GM foods are safe.

“In the last 10 years, the amount of yield I received last year, I never received such yield all my life and neither did my neighbors.†- Mohammed Rahmen

So how can farmers like Mohammed Rahmen, who are directly involved with and affected by the crop, begin to enjoy the benefits of GM crops if the public perception is so poor? How can scientists educate and assuage public fears associated with GM foods? These are the bigger questions that we must begin to address.

GM food crops will undoubtedly become more important and more relevant as the Earth's population grows and our amount of farmland remains the same. GM crops like Bt brinjal offer a way to improve crop efficiency and improve our future food security. However, if this type of miscommunication continues, it is more likely GM crops will be banned faster than farmers can get them in the ground.

Ellen Krall is an undergraduate at UGA studying Plant Biology. When she's not in classes or at the lab, she enjoys long walks in the State Botanical Garden, being kind of good at several instruments (violin, ukulele, banjo), and naming her Beta fish after famous scientists. More from Ellen Krall.

Ellen Krall is an undergraduate at UGA studying Plant Biology. When she's not in classes or at the lab, she enjoys long walks in the State Botanical Garden, being kind of good at several instruments (violin, ukulele, banjo), and naming her Beta fish after famous scientists. More from Ellen Krall.