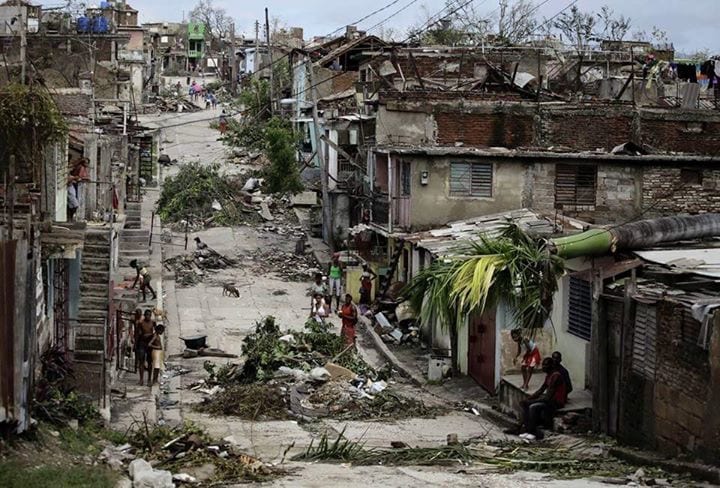

When disasters strike we see images of destroyed buildings, injured individuals, and the far-reaching devastation that accompanies the forces of Mother Nature. The media covers the aftermath for a few weeks, but then coverage slowly dissipates and people watching from afar forget about the struggle still facing those affected. But for these individuals, devastation and hardship can continue long after the disaster.

One such issue is the potential for disease outbreak when basic infrastructure breaks down. Lack of clean water and sanitation, crowded camps for the ill or displaced, and no previous immunity to new pathogens are all reasons why disease can follow in the wake of natural disaster. One of the most recent natural disasters to capture the United States' attention was Hurricane Matthew, which left Haiti devastated.

When cholera meets Haiti

In the wake of a 2010 earthquake Haiti was already facing a cholera epidemic, with cases increasing twofold after Hurricane Matthew hit the country. Cholera is a diarrheal disease caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae and can lead to severe dehydration and death if left untreated. The bacterium can be found in water sources when an infected individual may contaminate it with feces. The bacterium is transmitted when this water is consumed or used for food preparation. Areas with inadequate sanitation, hygiene, or water treatment are prime breeding grounds for Vibrio cholerae.

After the 2010 earthquake, cholera was allegedly brought to Haiti by United Nation peacekeepers. As the earthquake destroyed water treatment and sanitation infrastructure, the bacterium quickly spread and caused thousands to become ill. Since then, nearly 744,000 people have become sick with cholera and 10,000 have died from the disease. The combination of natural disaster, destruction of infrastructure, and bacteria from an outside source created the perfect storm to allow cholera to rapidly spread within the population.

Disaster in the form of cholera

Fast forward to early October 2016 when Hurricane Matthew came steamrolling through Haiti as a category 4 storm. In the hurricane's aftermath, sanitation and clean water were in short supply, leading to more than 5,800 suspected cholera cases by the end of October. To help relieve the burden of illness and death in the wake of Hurricane Matthew, organizations like UNICEF and the the World Health Organization responded by vaccinating 729,000 individuals against cholera. Despite these vaccination efforts, cholera infections are still occurring in Haiti. With more than 8,000 suspected cases since the hurricane hit, the battle with cholera continues.

Haiti and its battle with cholera is just one example of disease creating a long lasting impact months or even years after a natural disaster. Many factors, environmental or human, can contribute to increase disease transmission after disasters. But before disasters occur, there are preventive methods that can be taken to help prevent or limit disease transmission. Stockpiling adequate supplies of clean water, planning shelter and disaster facilities to avoid overcrowding, and vaccinating when applicable are just a few examples. Disaster does not always give ample notice, and these methods may not be implemented in time to help curb the spread of disease.

Natural disasters can occur in an instant and destroy all that we take for granted, from shelter and clean water to basic sanitation. The loss of infrastructure can create a perfect environment for a bacterium or virus to proliferate, leading to disease in an area that would never have had such issues before. You can also help those outside of your own community affected by natural disasters by supporting organizations like UNICEF and the International Medical Corps. After a disaster, these organizations help communities rebuild and work to prevent disease transmission. Because despite modern medicine and technology, Mother Nature can still exercise her power.