Whether you heard about it in your third grade history class or watched the iconic 1997 James Cameron film, almost everyone knows the story of the doomed luxury liner, Titanic. Trapped in a Murphy's Law situation, the ship sank on the night of April 15, 1912 after hitting an iceberg in the middle of the frigid North Atlantic Ocean, tragically claiming the lives of over 1,500 passengers.

Over 70 years passed after the disaster, during which the wreck of the Titanic sat in complete darkness and silence, lost at the bottom of the ocean until it was finally discovered by Dr. Robert Ballard in 1985. Researchers subsequently pounced to explore the more or less intact remains, collecting thousands of artifacts from the seafloor and taking samples from the deposited sediment. As it turns out, what they found on the microscopic level, a bacteria that has made its home inside the wreck, may prove to be the most important discovery of all.

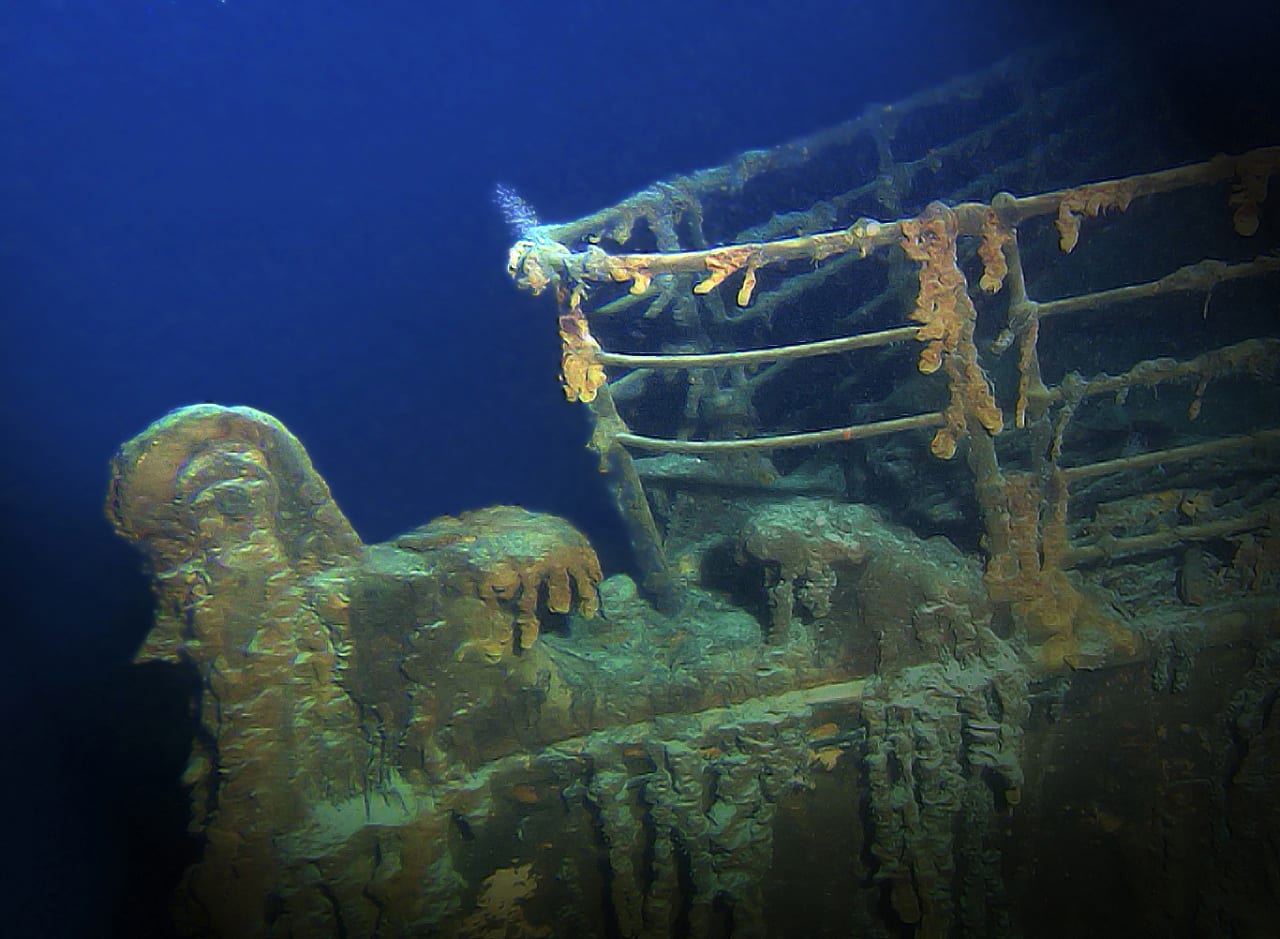

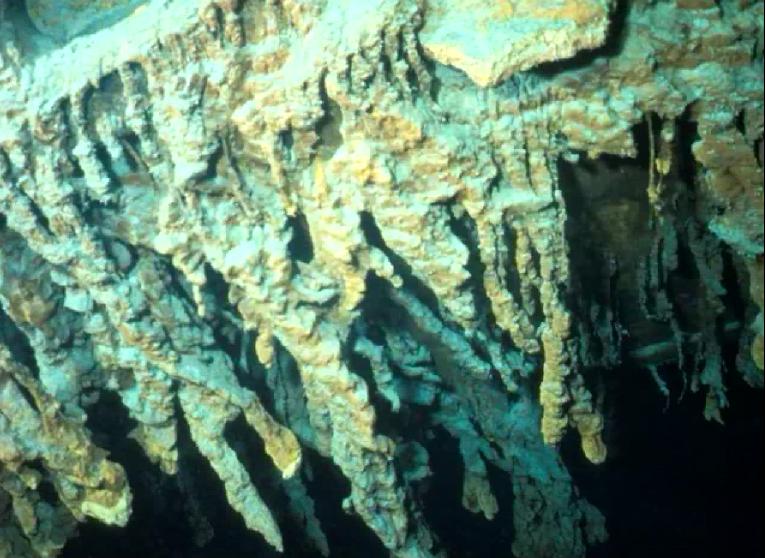

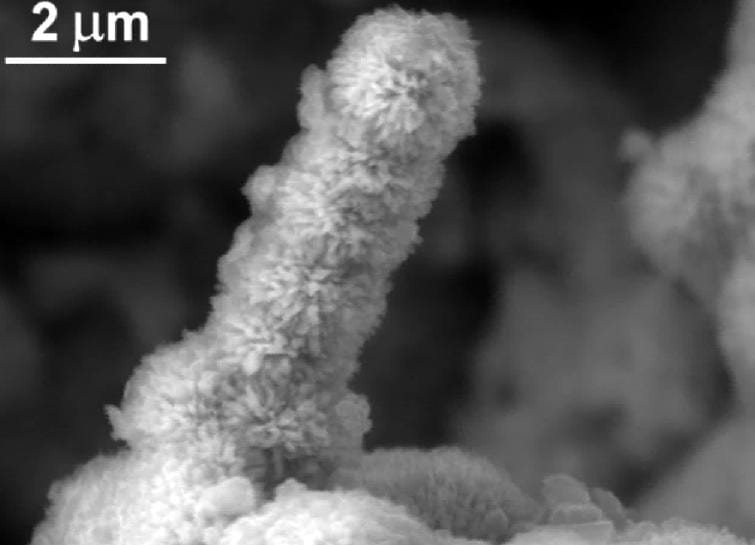

If you have seen photos of the ship's remains, you have probably noticed the strange, finger-like projections engulfing the entire wreck. These projections, called rusticles, house the bacteria Halomonas titanicae that is unique to the wreck and is currently eating away at the metal of the ship.

So while fans of the movie debate whether or not Jack and Rose could have both fit on that door, scientists are trying to figure out exactly how these munching microbes work. It is predicted that the rapidly progressing eating habits of the bacteria will reduce the Titanic to a pile of rust on the seafloor in approximately 10 to 15 years. Dr. Henrietta Mann, who discovered H. titanicae, points out that “Nature is very clever, and everything is recalled eventually. Nature makes it, and nature claims it back.â€

While nature may be reclaiming the wreck itself, nature might also be presenting an environmental solution in the form of this bacteria eating at the ship. If we know H. titanicae feeds on the iron of the Titanic, could it lend a helping hand in degrading other shipwrecks?

Scientists have recently been exploring the possibility of using H. titanicae as a bioremediation tool. Bioremediation is a technique that “treat[s] contaminants using natural methods,†such as microbes that can clean up pollutants, and in this case, marine debris.

Dr. Frank Loeffler, Ph.D. professor of microbiology at the University of Tennessee, states that, “Unlike a brute force approach, bioremediation can help make a very specific change to the system so that it heals. It has the potential to be not only cheaper but also environmentally friendly and acceptable to regulators and the public.†As an example, this process was applied during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, where microbes were used to clean petroleum from the surface of the ocean.

While H. titanicae won't be responding to any S.O.S signals from oil films on the surface, it could prove to be an excellent way to tidy up what lurks below. Even though shipwrecks can offer potential benefits such as new coral growth and shelter for a variety of marine species, many can also pose a threat to the environment by releasing pollutants including fuel, metals, and other toxic substances into the ocean. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association remarked in 2011 that, “Unless they posed an immediate pollution threat or impeded navigation, most wrecks were left alone and largely forgotten – unless they began to leak.†Researchers believe H. titanicae could be harvested from the Titanic and used to “accelerate decomposition of shipwrecks littering the ocean floor,†reducing the threat of these leaking wrecks by safely and quickly eating away their metal structure. This would eliminate any chance of damage to passing ships that a wreck could cause, and then other bioremediation strategies could be implemented to remove oil-related contaminants.

As it turns out, the ill-fated Titanic could end up having a lasting, beneficial impact on the very ocean that claimed it over a century ago. Over two miles deep, the tiny living products of this tragedy pose a potential environmental solution just waiting to be explored. We may have lost Jack, but our hearts will go on as we discover new, innovative ways to clean up our marine habitats.

Featured Image Credit: Daniel DRV via Flikr

Savanah Jackle is an undergraduate student studying Biological Engineering with an emphasis in biomedical engineering at the University of Georgia. In addition to her studies, Savanah loves working with elementary school children to teach them about STEM concepts. With her education and training, she would like to go into either medical machine design or the prosthetics industry, and also continue her work in encouraging young women to pursue careers in engineering. If she's not hanging out in Driftmier Engineering Center, you can find Savanah hiking outside or trying hopelessly to keep up with her crazy beagle, Olive. And no, that's not a typo. She really spells her name with one “n.†You can e-mail her at savanah.jackle25@uga.edu or connect with her on Twitter. More from Savanah Jackle.

Savanah Jackle is an undergraduate student studying Biological Engineering with an emphasis in biomedical engineering at the University of Georgia. In addition to her studies, Savanah loves working with elementary school children to teach them about STEM concepts. With her education and training, she would like to go into either medical machine design or the prosthetics industry, and also continue her work in encouraging young women to pursue careers in engineering. If she's not hanging out in Driftmier Engineering Center, you can find Savanah hiking outside or trying hopelessly to keep up with her crazy beagle, Olive. And no, that's not a typo. She really spells her name with one “n.†You can e-mail her at savanah.jackle25@uga.edu or connect with her on Twitter. More from Savanah Jackle.