It all began with an occasional, achy pain in my stomach area after I ate. This pain was generally accompanied by lots of belching and severe bloating (my belly would become distended and hard to the touch). The symptoms didn't happen often so I didn't worry about it, but the pain increased in severity and frequency until it was happening almost after every meal. The pain would radiate like a searing hot knife slashing throughout my entire abdomen and I often ended throwing up.

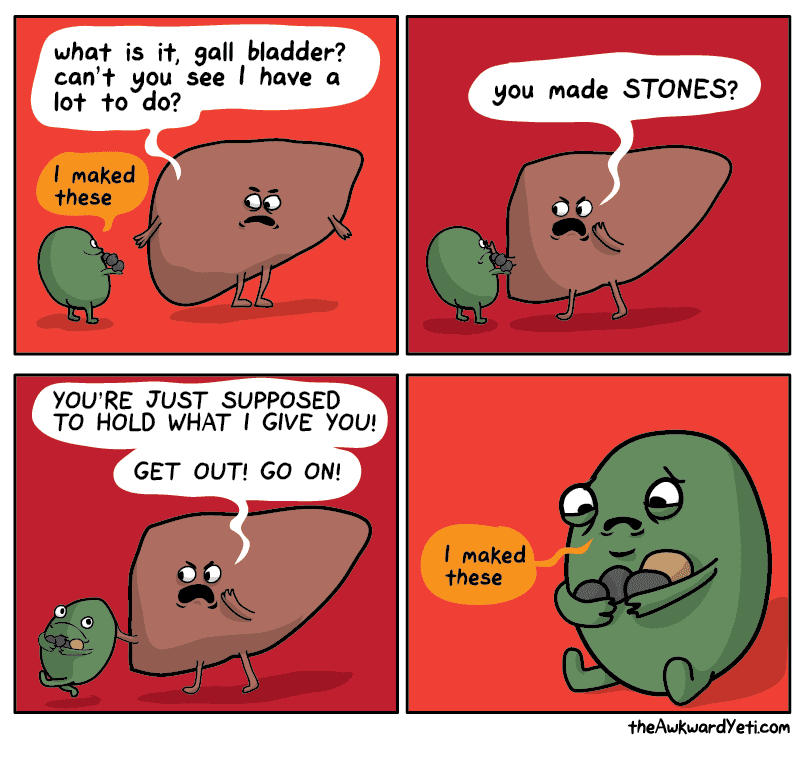

I figured this wasn't just your normal run-of-the-mill digestive problem, so I went to see several different doctors. The first doctor thought I had heartburn. The second thought it was stomach ulcers; so I had to wait two hours in line to poop in a cup, and then another 3 weeks to be told that H. pylori was not the culprit. After months of waiting, several blood tests, countless hours on WebMD, and an ultrasound, I was finally diagnosed with gallstones. My pesky gallbladder wasn't properly getting rid of the bile it was storing and was causing me A LOT of pain.

So how do you remedy gallstones? In most cases, surgical removal is required, and that is what I did. Fast forward a few months: I am sans-gallbladder and symptom-free. This situation got me thinking, why do we have organs that we can live without? It seems contradictory to me that my life would be better after removing a portion of my body.

As it turns out, we have some body parts that are vestigial, meaning that they have lost all or most of their original function through evolution. Some examples of human vestigiality are the appendix, coccyx, wisdom teeth, plica semilunaris of the conjunctiva, parts of our reproductive system, and much more. As you can see, my problematic gallbladder is not included in this list because it does indeed serve a function.

In fact, we have several function-serving organs that we can live totally without: the spleen, reproductive organs, the stomach, the colon, gallbladder (good riddance), tonsils, and sensory organs. You can even live without one organ out of a pair and parts of some organs: a kidney, parts of your liver, half of your brain, a lung, and possibly more that aren't listed here. Hey, you can even live without limbs! You get the idea; there is a good deal of you that you could do without.

So why can we get away with losing half of an organ pair, part of an organ, or, in some cases, losing the organ entirely? Redundancy in organ or organ function may help us live longer. Just think, if one of your kidneys becomes non-functional, you still have another one to rely on. In some cases, organs can be removed to avoid the consequences of certain diseases, like gallstones.

Gallbladder removal due to gallstones is one of the most common surgeries in America. Gallstones runs in families and occurs mostly in women, likely due to increased estrogen levels. Living without a gallbladder is possible even though the gallbladder has functions including aiding fat digestion, absorption of fat soluble antioxidants and vitamins (A, D, E, and K), removal of cholesterol from the body, and assisting toxin removal from the liver. Having your gallbladder removed does come with some risks. For example, people without a gallbladder have a higher risk of developing fatty liver disease and deficiencies in certain nutrients are common.

In some cases of organ removal, your body will compensate for its removal. For example, even though I am living without a gallbladder to store my bile, my liver compensates by constantly trickling bile out into the intestines. Due to the loss of the gallbladder, some people may need to eat a low-fat diet to avoid diarrhea after a fatty meal because not enough bile is around in the intestines for absorption of nutrients. It is also recommended to supplement your diet with fat soluble vitamins and to take digestive enzymes to avoid indigestion. I, however, am very lucky. My diet is virtually the same now as it was before I got my gallbladder removed.

While removing an organ seems like a gruesome and painful act, I only have a couple of tiny scars to show for it and I am so very grateful that my gallbladder is gone!

About the author

|

Katherine Kruckow is a graduate of the University of Georgia with a Bachelor’s degree in Microbiology. She is looking for a PhD program to further her passion of studying microbes. When not in the lab she loves hiking, cooking, going to all the concerts she can afford, and reading a good book in her hammock. She also plans on visiting every national park at some point in time during her life. Contact her at kkruckow@uga.edu.More from Katherine Kruckow. |

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020