Picture a dairy cow with the black and white spots we all know and love, mooing happily in a grassy field. Does this dairy cow have horns? In your mind's eye, it shouldn't. But that's only because the horns are removed when the cows are young, around four weeks old, with a procedure called disbudding. The benefit of hornless cattle is twofold: it protects other cattle and it protects animal handlers. Currently, disbudding involves destroying the premature horn tissue on young calves. This process is performed in multiple ways, but all are rather unpleasant: cauterization, a knife, or caustic dehorning paste. While pain from this procedure can be mitigated with the use of local anaesthetic, unfortunately, the vast majority of cattle are disbudded without it, as it must be administered by a veterinarian (adding costs to producers). This presents a huge animal welfare issue as the vast majority of dairy cows born for US animal agriculture, male or female, undergo this procedure.

To tackle this problem, the biotech company Recombinetics along with Alison van Eenennaam's lab at UC Davis have replaced the gene for horns in Holstein dairy cows with the “polled†horn absence gene found in hornless cows, such as Angus beef cattle. You can watch Recombinetics's video discussing disbudding and their gene-edited dairy cows here. It's a PR gold mine for gene editing: polled dairy cows solve the animal welfare concern of disbudding. Additionally, this technique avoids any unwanted genetic changes to the cows, as only the horn gene is altered.

Unfortunately, with the negative opinion many have towards genetic modification (GM), funding and support for gene editing is at an alltime low. Most of this is a result of misinformation about GM (check out Patrick Griffin's article about GMOs to learn more). This means that the goal of eliminating disbudding for dairy cows is at risk, along with all other research that involves gene editing in animals. To understand how we reached this point, we need to look into the history of genetic modification in animals beginning in the 1990's.

The first genetically modified animal species to be potentially be introduced into U.S. markets were AquAdvantage Salmon in 1996. These fish were designed to grow to be much larger than their Atlantic salmon relatives from the deep ocean, allowing for more meat to be obtained from the same number of fish (and thus providing more profit to producers). To create these salmon, scientists at AquaBounty manipulated systems already present within them: wild Atlantic salmon have a growth hormone gene that does not function during the winter season. The researchers introduced a stronger growth hormone gene from a larger species of salmon and made sure it was always active. With this, the AquAdvantage Salmon are growing larger throughout the entire year.

While AquAdvantage Salmon have the potential generate huge profits for AquaBounty, the FDA held them from the US market for more than 15 years pending published data that the fish were safe to eat. Many questioned the safety of increased hormone levels in the genetically engineered salmon with the concern that they may pose health risks. However, as of 2010, the FDA declared AquAdvantage Salmon to be as safe as wild salmon for human consumption. Despite the FDA's approval, AquAdvantage Salmon are currently being kept from the market by the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016, a spending bill that includes a provision indirectly requiring the FDA to mandate the AquAdvantage Salmon be labeled as GM. Additionally, with consumer opinion of the salmon being incredibly low, many major grocery chains, including Costco, have released statements that they will not sell GM fish.

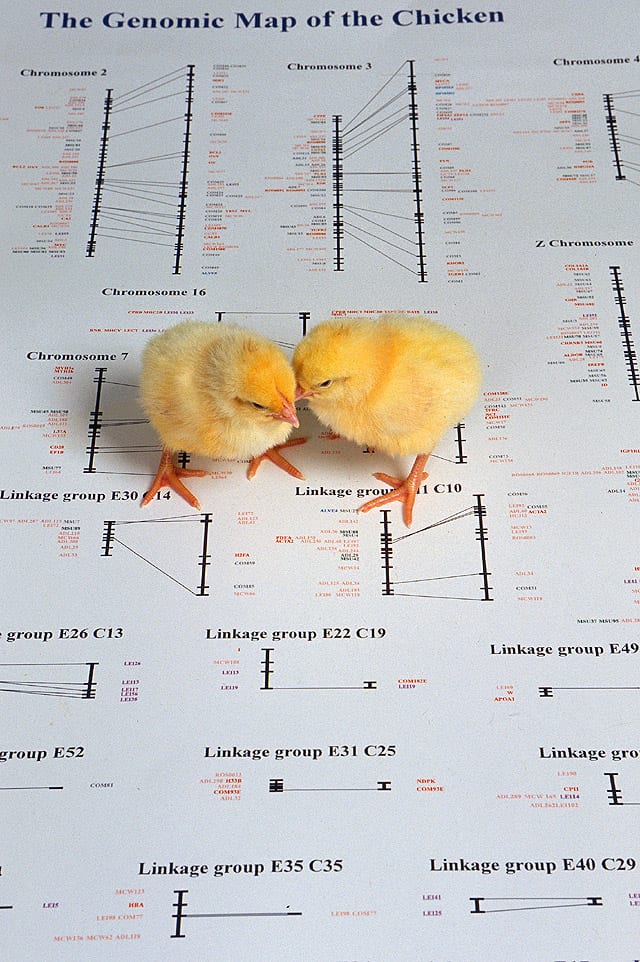

Here, we strike the culmination of decades of fear and misinformation regarding GM. Backlash against the use of GM in food production has prevented the widespread success of this technology for all of its potential applications. This not only includes the welfare of Holstein dairy cows, but other animals as well: Recombinetics strives to use gene editing to eliminate the culling of newborn male chicks—a nearly universal practice in the poultry industry.

We can't go back in time. But maybe looking back it would have been better for public opinion of genetic modification if the first modified animals were hornless cows instead of super-sized fish. Polled dairy cows present no threat to the direct consumer product, the milk itself; the only genetic changes are to the horns. Without governmental and consumer support, polled dairy cows may never enter the U.S. agricultural market. Perhaps if we laid the foundation for genetic modification in animals with the intent to solve animal wellness concerns, rather than to solely provide profit to the producer, the general public's perception of genetic modification would be vastly improved today. It would be a win for the animals, too.

About the Author

Tina Ethridge is an undergraduate studying Applied Biotechnology with a minor in Genetics at the University of Georgia. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, cycling, and going on adventures with her retired racing Greyhound. Her favorite place to enjoy nature is at the top of Yonah Mountain in Helen, GA. |