Imagine for a moment that you have just welcomed a beautiful baby into the world. Over the next fourteen days your baby multiplies 3,000 times in size to that of an elephant, climbs up a tree, tears off its skin, and 10 days later flies away as a pterodactyl. This probably sounds like a ridiculously strange and poorly thought out horror movie, but for many insects this is the norm thanks to the spectacular process known as metamorphosis. But how exactly does a chubby little caterpillar manage to recreate itself as a majestic ornament of the skies? Because monarchs happen to be my particular area of expertise, they will serve as our primary subject as we examine what really happens when an insect transitions from caterpillar to butterfly.

The Beginning

A 1st instar monarch caterpillar that has just hatched and consumed its egg shell. Notice that it lacks the characteristic bright yellow coloration. This doesn't appear until it starts consuming its milkweed host plant. (Photo credit: Wendy Caldwell)

- A hungry first instar caterpillar nibbling away at its egg shell shortly after hatching. (Photo credit Siah St. Clair)

When our monarch caterpillar hatches from its egg, its first act is typically to eat its own egg shell. Even though it is only 2-6 mm long, our caterpillar already contains the blueprint for the butterfly to come. These blueprints, called imaginal discs, are dormant clusters of cells for each structure present in the adult body—ie. legs, wings, antennae, genitalia. As a caterpillar, a special hormone called the juvenile hormone keeps these clusters of cells from replicating and ensures our caterpillar stays a caterpillar.

Once it outgrows its skin (called the cuticle), the hormone ecdysone is released triggering the insect to molt. First, the head capsule pops off (imagine your face falling off and regrowing); then the caterpillar wiggles out of its old skin, pulling one pair of legs out at a time like an old pair of skinny jeans. The molting stage is a vulnerable time for caterpillars because their new cuticle offers little protection and their new mouthparts are too soft for them to eat. Once a caterpillar completes molting, as its younger self had done before, the freshly molted caterpillar turns to its old cuticle for its first meal. Waste not, want not!

Monarchs go through 4 of these molts, and thus have 5 developmental stages called instars. After two weeks, a sharp drop in the juvenile hormone allows cells in the imaginal discs to replicate triggering the 5th and final molt that results in pupation (the formation of a chrysalis).

Just a big bag of goo?

Now a chubby, two-inch fifth instar, our caterpillar has outgrown its final cuticle and is ready to pupate. Crawling off of its milkweed host and it lopes off to find a sheltered, secure place to form its chrysalis. This could be the underside of a leaf, a lawn mower or the side of your house depending on the caterpillars mood. After spinning a silk pad to anchor itself, the caterpillar will turn around and grip the silk with its last pair of prolegs before gently lowering itself upside into the shape of a ‘J.'

While our caterpillar still looks totally normal, enzymes in its gut called caspases trigger a programmed self-destruction of all non-essential tissues aside from the imaginal discs and integral parts of the brain like the mushroom bodies (responsible for olfaction and memory). The digested structures form a protein-rich fuel for the prolific growth of the imaginal discs. This liquefaction process has probably also fueled the misconception that a chrysalis is just a bag of goo!

If your timing is impeccable, you can see the skin right behind the caterpillars head split open, exposing the pupa forming beneath. The caterpillar will wriggle its final cuticle all the way up to the top until only its last pair of prolegs (the stumpy abdominal legs) are holding it up. Then, in a truly impressive maneuver, the caterpillar must release its prolegs and stab a stem-like structure (called the cremaster) into the silk pad to hang itself. After driving in the cremaster, the forming pupa will begin to aggressively twist back and forth. If you looked under a microscope you would see that the cremaster is covered in tiny hooks and thus by twisting the pupa can ensure that it is anchored securely. If the pupa falls, there is little chance of survival.

In these photos you can see the monarchs skin splitting and the pupa wiggling it up its body. Between the second and third photo the monarch attaches the cremaster. Photo credit Siah St. Clair

Even as the pupa is forming you can already see the components of the adult butterfly. The outline of the wings is clearly visible as well as the antennae, proboscis (essentially a feeding tube), and abdominal segments. Though the pupa hardly seems to be alive, it still breathes through spiracles like the caterpillars and adults and even has a ‘heartbeat,' pumping hemolymph (insect blood) throughout the pupa.

A butterfly at last!

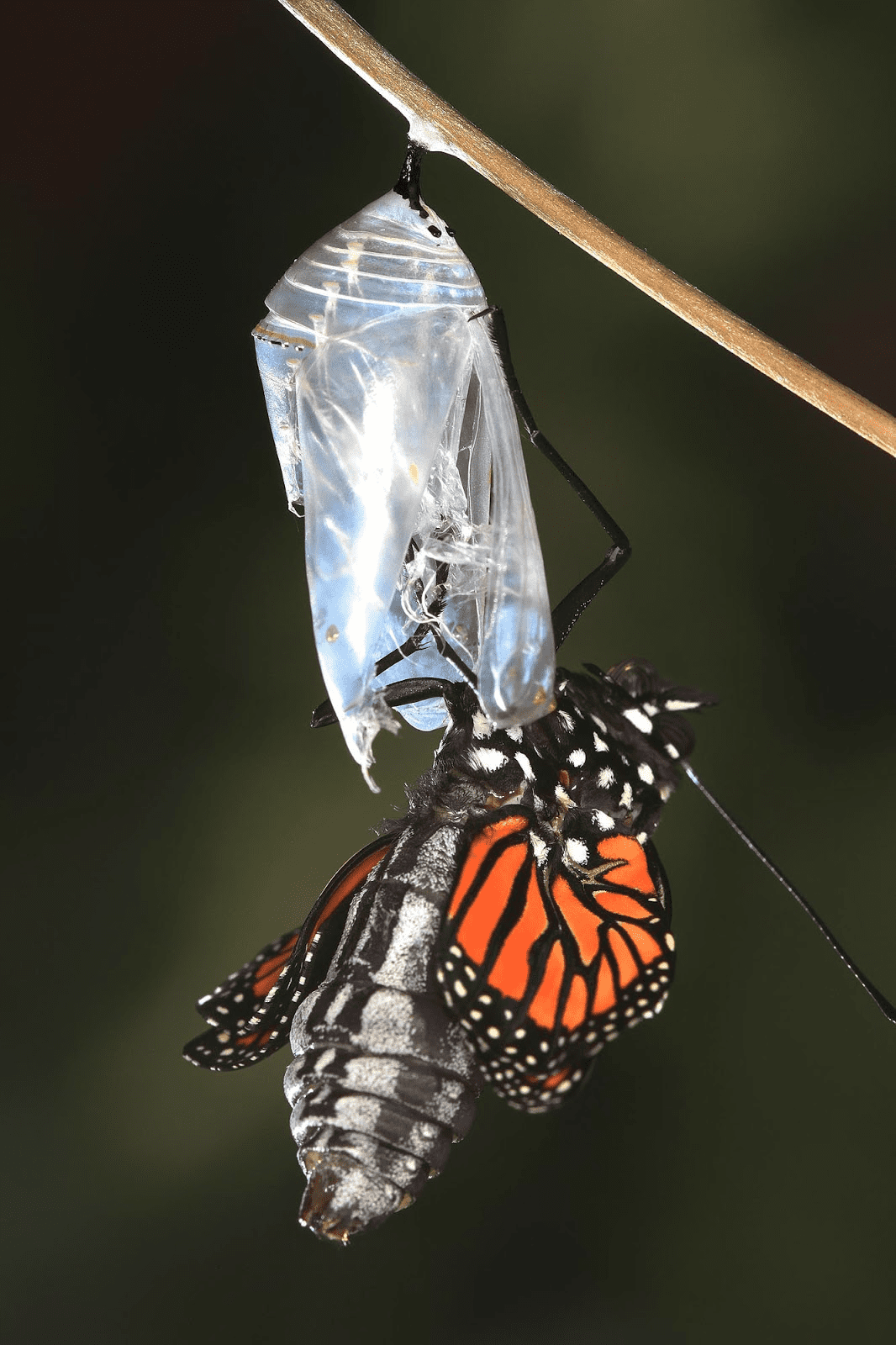

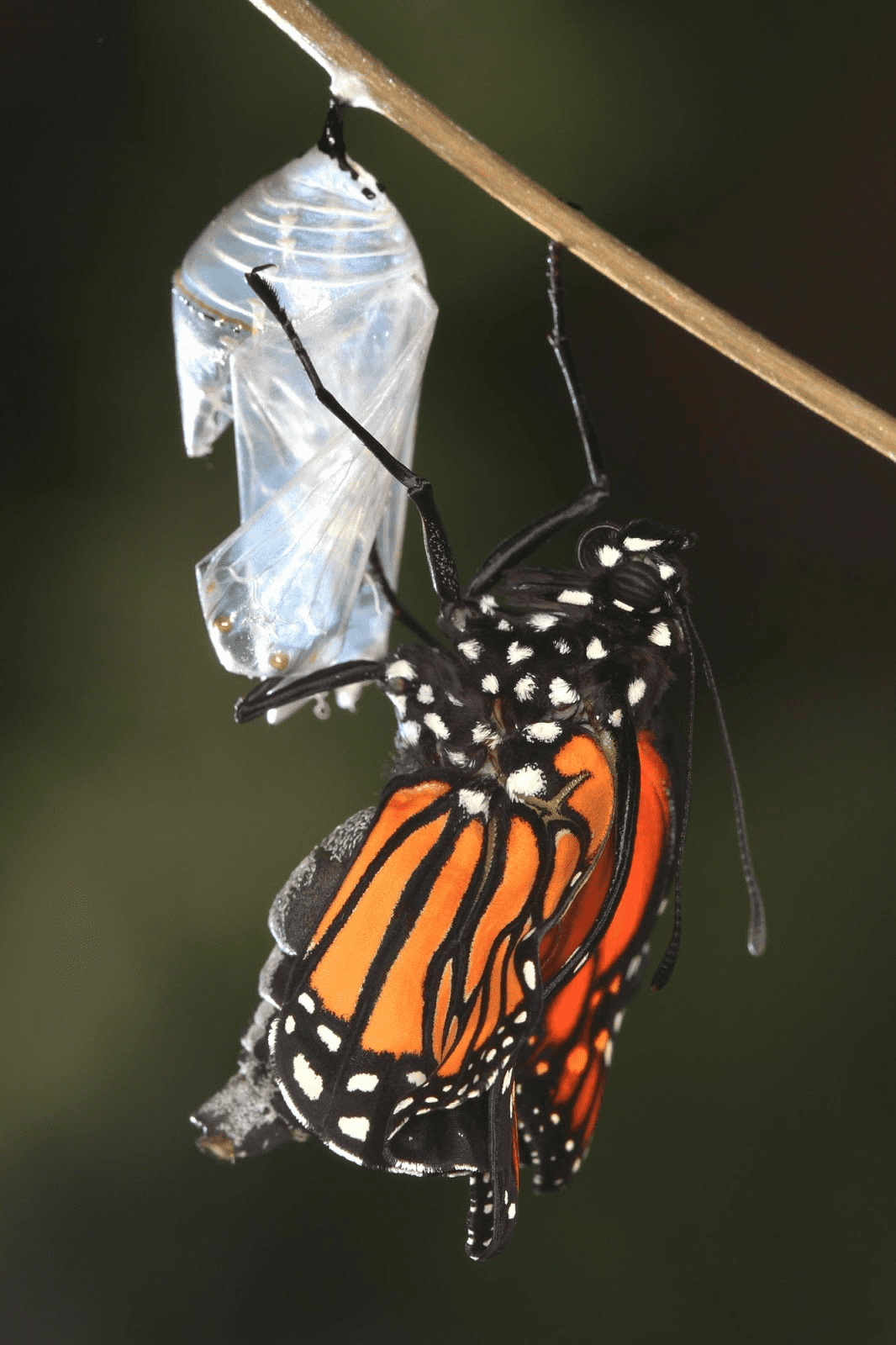

After 10-14 days the pigment finally develops and the bright pattern of the monarch wing becomes visible through the chrysalis. When the monarch finally bursts from the chrysalis, its abdomen is enormous and its wings are shockingly small. Over the next 30 minutes, it pumps fluid from its abdomen into the wings to expand them. Once fully expanded their wings are still flimsy and delicate like wet paper and thus it takes another few hours for them to dry and harden enough for flight.

You might be wondering if our majestic butterfly has any memory of its past life as a hungry, chubby caterpillar. It turns out they do! One study found that caterpillars that were subjected to an electrical shock remembered the smell associated with being shocked as an adult butterfly! This is likely due to the mushroom bodies in the insect brain which, as you may recall, are responsible for memory and olfaction. However, this study demonstrated that this post-metamorphic memory was only detected when the shock was applied to late stage larva, indicated these regions of the brain are not formed until late in larval development.

A monarch eclosing (emerging) from its chrysalis. Around 30 minutes elapses between the first and last photo. (Photo credit Siah St. Clair)

And just like that, our new butterfly flaps away to live its new life in the skies. Maybe it will even make the trip all the way to Mexico! Click HERE to learn about the epic monarch migration and more reasons why monarchs are amazing.

About the author:

|

Hayley Schroeder is an undergraduate at UGA studying Ecology and Entomology. She is an enthusiastic foodie, advocating for food that nourishes not just the people eating it, but communities, farmers and the earth as well. She is also a friend to all insects and can be easily spotted on campus by her butterfly net. Contact her at hayleyadair37@uga.edu. More from Hayley Schroeder. |