When I was little, my favorite thing to do was draw pictures. Crisp white printer paper and a mega box of crayons were all I needed for endless hours of entertainment. My love for artistic endeavors remained with me throughout my adolescence in the form of music lessons and sketchbooks, but in elementary school, I discovered my next passion: science.

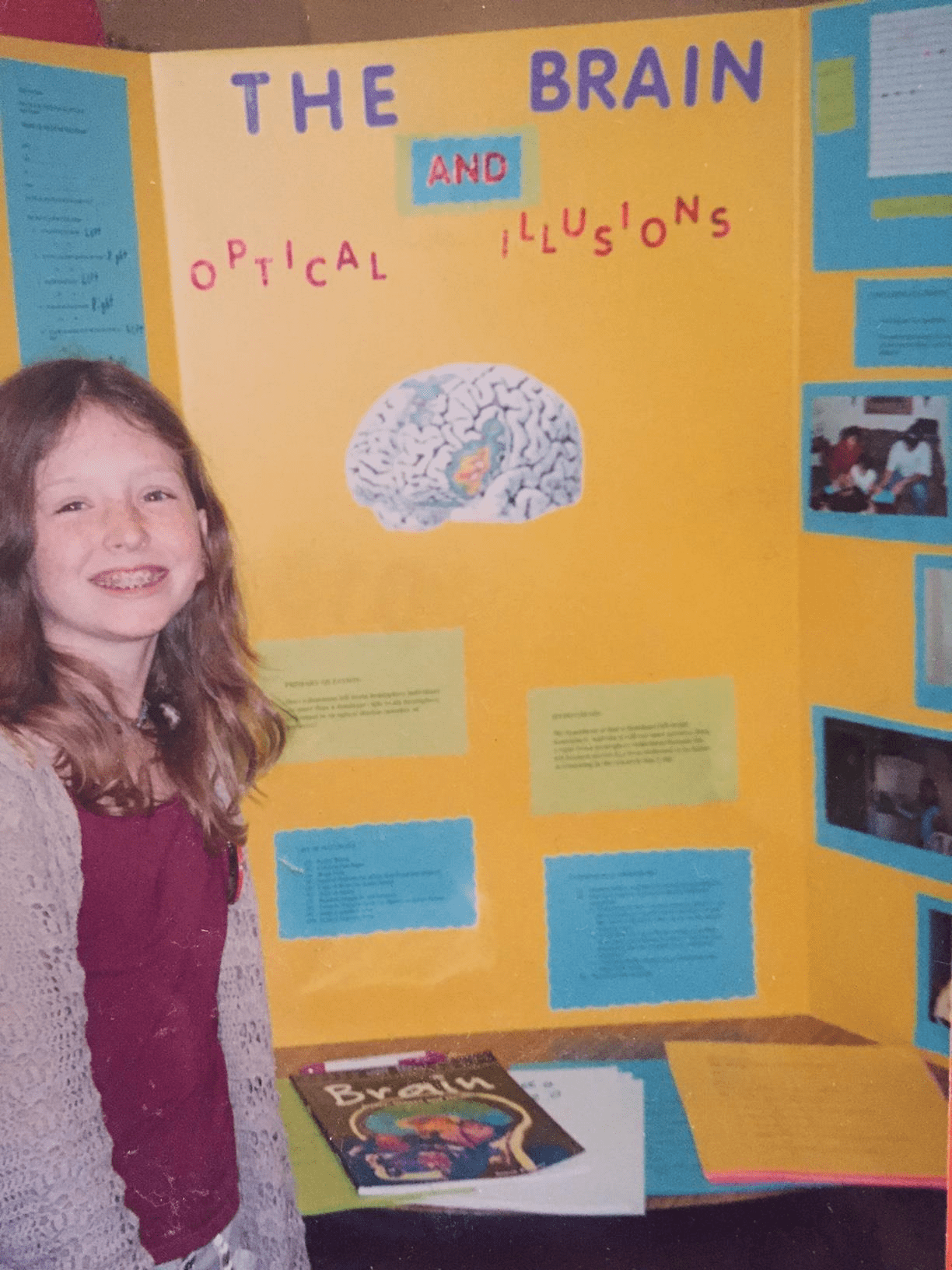

Every year at Frey Elementary, my brother and I would participate in our school's science fair, but my 5th grade experiment was definitely the most memorable. I titled my presentation “The Brain and Optical Illusions,†where I explained my data from testing the observation skills of my friends, neighbors and family with a series of optical illusions. My experiment won first prize in my school and it went on to win first prize at the county level as well!

Today, I'm happy to say that both my artistic and scientific endeavors are still prominent in my life. Until recently, though, I have always thought of these passions as separate, discrete parts of my personality. I saw art as much more evocative and emotional, while I viewed science as fact-driven and unfeeling. But more and more, I'm seeing that these traditionally opposite disciplines make a powerful and beautiful combination.

The Historic Connection between Art and Science

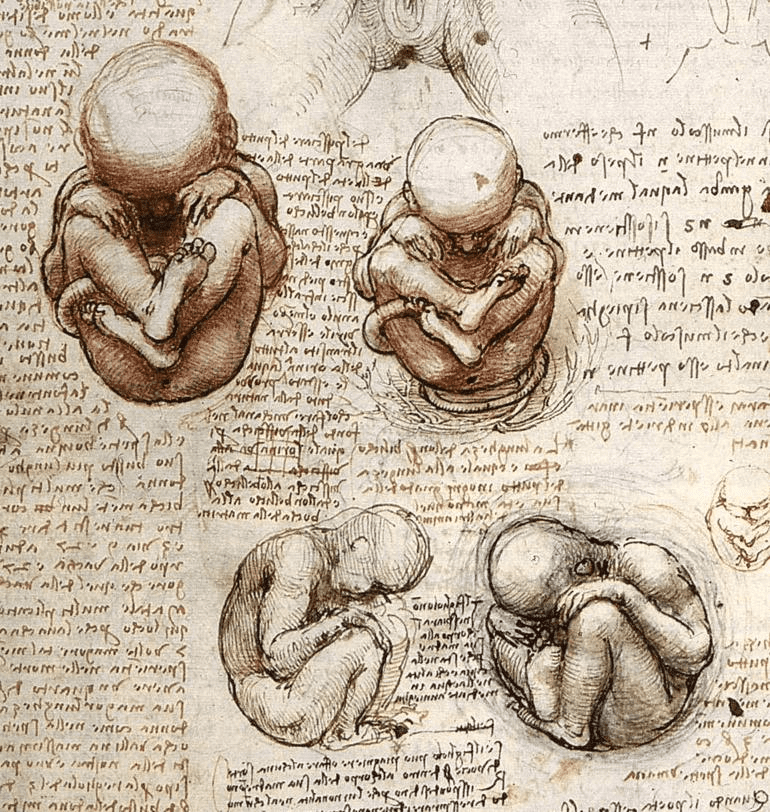

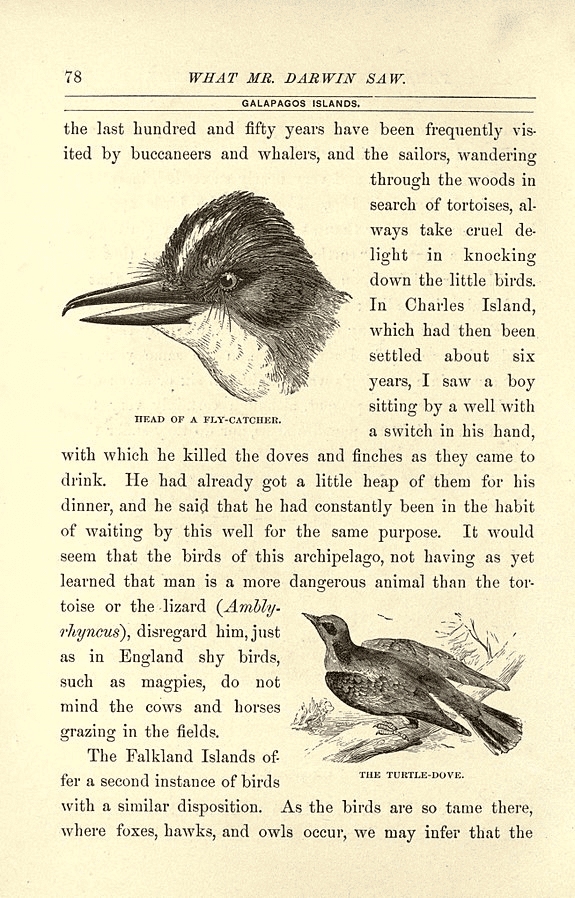

Historically, science and art have always been undeniably connected. Before the advent of graphic imaging or advanced photography, good scientists had to be good artists. Their illustrations were necessary to accurately convey their subject matter. Examples of these artistic scientists can be seen throughout history. In the 1st century A.D. Pedanius Dioscorides wrote and illustrated De Materia Medica, a book documenting around 600 plant species and their medical applications. This famous book was common literature through and beyond the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci was more of a scientific artist- he was famous for his artistic renderings that were informed by careful observation of human anatomy, plants and birds. Charles Darwin's illustrations from his well-known journey through the Galapagos were published and later integral to conveying his evolutionary theories. Not only were all of their illustrations immeasurably important to the success of their work in the short term, they were also important in advancing science literature as a whole.

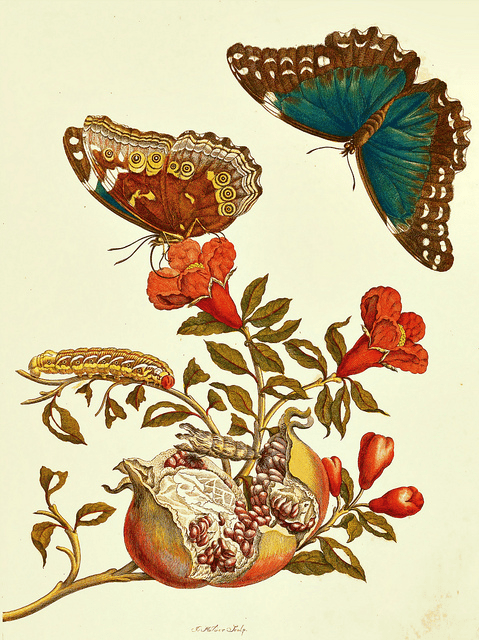

One forgotten scientist who exemplifies the science-art connection was Maria Sibylla Merian, an entomologist and scientific illustrator who lived in the 17th century. Rather than subjecting herself to convention, she dedicated her life to the study of butterflies, moths, and silkworms. Merian was a pioneer in her work- it was still common knowledge during this time that insects were born through a “spontaneous generation of rotting mud.†Merian challenged this notion when she published her two volume exploration on insect metamorphosis when she was only 28. Her first publication was self illustrated with unique, compiled illustrations of butterflies at different stages in their lifecycle. In 1699, Merian visited the small island country of Surinam in South America to study butterflies in their natural habitats and went on to publish more beautifully illustrated books based on her research there. Merian is largely unrecognized in her field because of the discrimination towards female scientists during this time, but her artwork and intellectual work live on as a beautiful example of the synergy of art and science.

The Science-Art Connection in Modern Day

Scientists largely continued to illustrate their own work through traditional media – oil, watercolor, gouache – until the advent of the computer during the early 21st century. Graphic artists have largely taken over scientific illustration, but there are still many forms of scientific art and illustration today.

Scientific illustrations by graphic artists can make a seemingly complex scientific topic palatable for the general public, and can even give the most experienced scientist a new point of view. For example, 3D animations of microbiological processes too small to witness with our own eyes give us insight on how the microbiological world functions. And if you have ever owned any kind of scientific textbook, I 100% guarantee there is a graphically designed figure or picture somewhere between the covers. Textbook illustrators' figures are reaching one of the largest audiences in the world – students. With around 65% of people categorizing themselves as visual learners, their art is one of the most important in the scientific community. Because of the evident importance of the arts to science, there is even a current initiative to integrate art and design into the STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) disciplines.

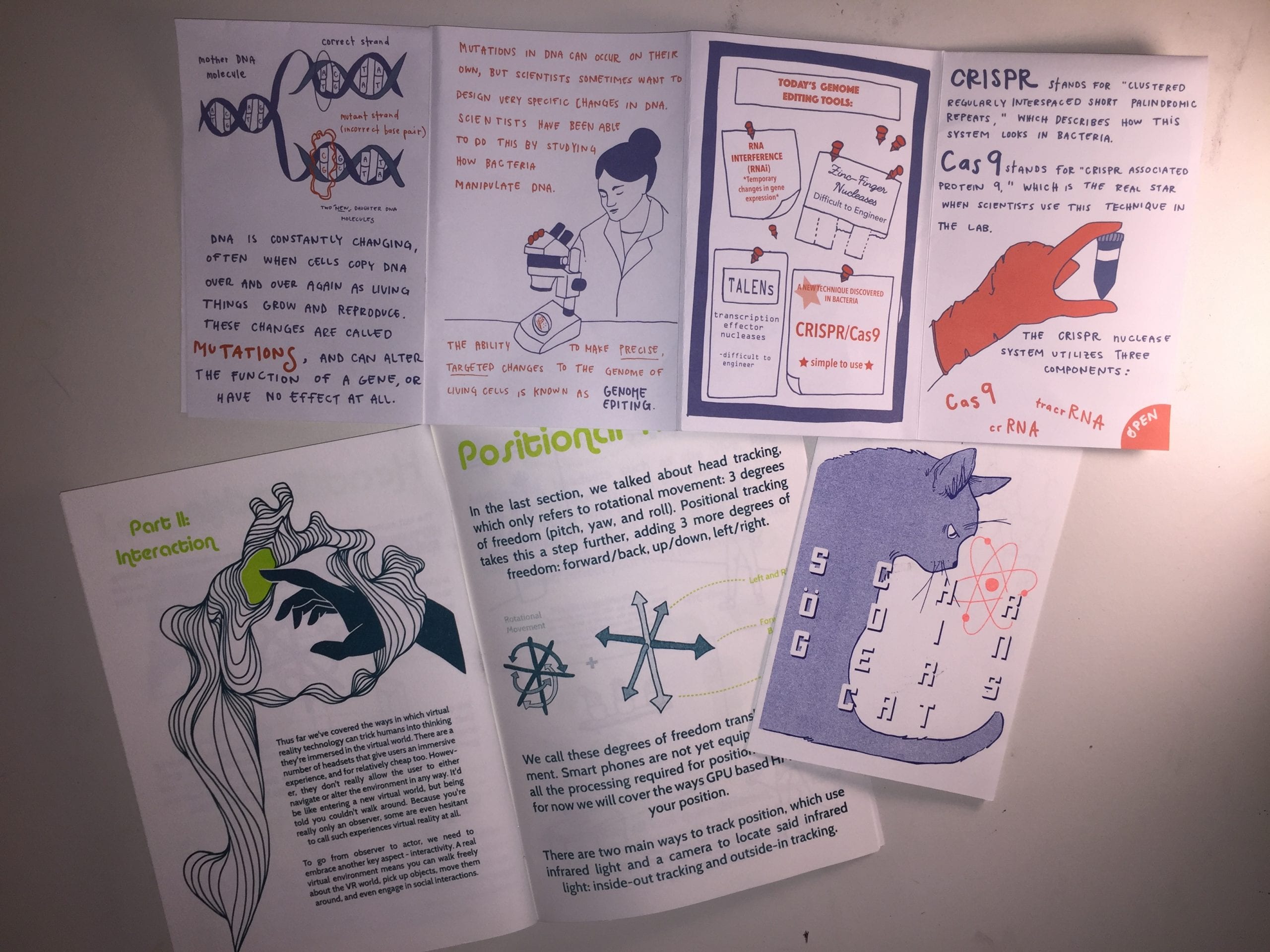

Other important organizations are focusing on making science accessible and understandable to the general public through art. One example is Biocanvas, a blog that displays beautiful, ethereal images of scientific subject matter ranging from microscopic fungi to images of our universe from outer space. Another is Two Photon Art, a collaboration of two artistic scientists that work together to condense complex scientific topics into fun, easy-to-read zines.

In our fast-paced, social media driven society, scientific misinformation is often easier to spread than accurate scientific fact, so scientific artists and artistic scientists may be the missing link to popularize accurate, easy-to-understand science.

Separately, science and art are often viewed as elitist worlds filled with unintelligible jargon and complex techniques. But together, they combine synergistically to form something greater than the sum of their parts. When combined, cold, hard science seems a little bit warmer and abstract, elusive art has broader contexts. I'm excited to see what the future holds for this relationship and all the new manifestations of my two passions: art and science.

About the author:

|

Ellen Krall is an undergraduate at UGA studying Plant Biology. When she's not in classes or at the lab, she enjoys long walks in the State Botanical Garden, being kind of good at several instruments (violin, ukulele, banjo), and naming her Beta fish after famous scientists. More from Ellen Krall. |

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020