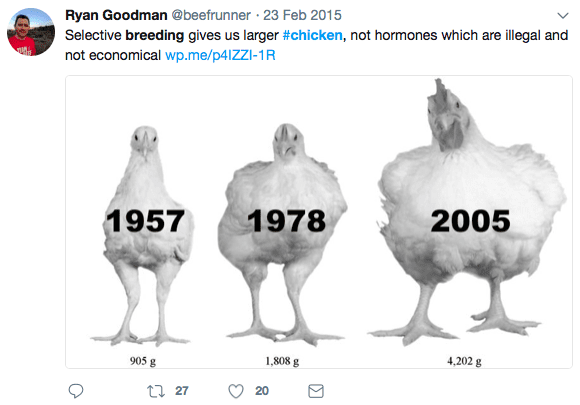

Today's chickens are bigger than ever before, which raises the question – how did we do that? Over the years, companies have selected chickens with the healthiest growth and size for breeding, to help them get the best start possible. Understandably,food animal production is an emotionally-charged topic, and with conflicting information readily available online and on social media many consumers' are concerned and frustrated. And, with the poultry industry contributing over $18.4 billion to the Georgia economy each year, this topic is quite literally in our own backyards.

Let's start by having an honest conversation about commercial chicken production and debunking common misperceptions. A 2015 survey conducted by the National Chicken Council revealed that nearly 80% of consumers believe chickens are genetically modified, pumped with artificial hormones and steroids, or some combination of the two. Similarly, 73% of consumers believe that antibiotics are present in most chicken meat. Well, we can put those rumors to rest. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) enforces federal regulations that prohibit the use of added hormones and steroids in all poultry. The USDA also regulates withdrawal periods to ensure no meat consumed contains antibiotics or antibiotic residue from animals that may need medicine.

What sort of voodoo is this? What makes chickens today so efficient? The road to bigger chickens begins with good breeding. Prior to the 1950s, chickens were dual-purpose, used for egg production and occasionally for meat. However, these qualities are negatively correlated attributes, meaning a bird that produces more meat will produce fewer eggs and vice versa. This encouraged the introduction of breeding for a specific purpose. Chickens used for meat production are called broilers, which are a genetic cross of the Cornish breed and the White Plymouth Rock breed. In contrast, chickens used for egg production are the Leghorn breed.

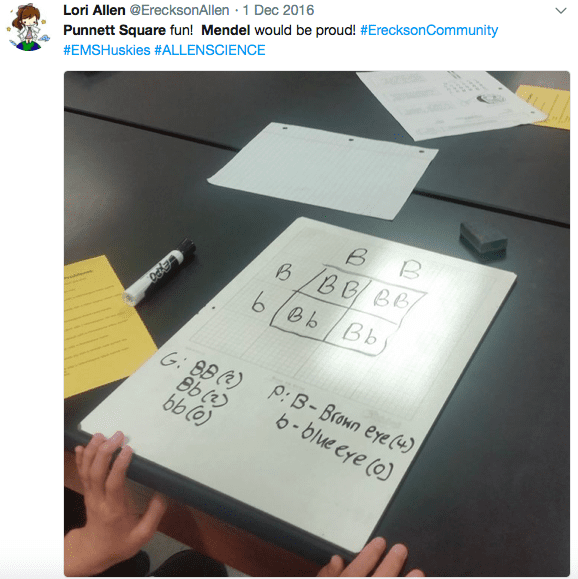

Chickens raised in the U.S. benefit from a natural process of selecting and cross-breeding birds with the most desirable qualities. This is done through good ol' fashioned Mendelian genetics. Everyone remember the guy with the peas and the Punnett square?

Primary breeder companies promote genetic improvement and multiplication to meet market demands for chicken. To put it simply, geneticists want to mate the supermodels and the bodybuilders of the chicken world to get the highest quality offspring possible. Ideally, the offspring will be better off than either parent, similar to when two very attractive A-list movie stars have a child who is even more attractive than either parent. Two natural attributes have contributed to the genetic improvement of poultry: the large number of eggs produced by hens (more offspring means more opportunity for genetic progress within one generation) and the short generation interval (within 20-25 weeks a hen will begin to lay eggs, therefore, the time from generation to generation is very short). However, it takes 5 generations or more to pass a trait down to the eggs and meat that we eat.

Consumer trends have largely dominated the poultry needs within the U.S. For instance, between the 1960s and 1980s, the poultry industry continued to make genetic improvements and increased breeding for the production of white meat. In the 1990s and 2000s, consumer preference for cut-up and further-processed chickens, as compared to the traditional whole bird, led to the development of specialized breeding to meet these markets.

Through breeding specialization, the poultry industry is able to provide a safe and continuous food supply to consumers at a cost-effective rate. Chickens are an affordable source of protein because broiler chickens gain more weight with less feed. Today's broiler can achieve a 5-pound market weight in 5 weeks, whereas 40 years ago, it took 10 weeks to achieve a 4-pound market weight. On an average day, Georgia produces 31 million pounds of chicken.

Likewise, breeding specialization also allows eggs to be relatively inexpensive because of the ability of laying hens to lay many eggs in a row. Fun fact, the color of a chicken's eggs can generally be determined by looking at the color of its earlobes! Interestingly, brown eggs still tend to cost more at the store. This fact has led many people to believe that brown eggs are healthier or higher-quality than white ones. However, the cause of this price gap is actually quite different. Brown eggs used to cost more because brown-laying hens produced less and weighed more. While that’s no longer true, brown eggs still come with a higher price tag. So next time you are cruising the egg aisle remember that there is no nutritional difference between brown and white eggs.

In addition to the success of primary breeding companies, chicken farmers now better understand the kind of environment the chicken needs to make the most of its genetic and nutritional potential. Modern advances in farming including advanced housing, climate controls, and biosecurity paired with good animal husbandry and collaborative relationships between farmers and veterinarians help us raise larger, healthier chickens. Antibiotic, hormone, and steroid free!

Lydia Anderson is a Dual DVM-PhD graduate student at the University of Georgia. Since completing her PhD in Infectious Diseases, she has been working on her DVM at the College of Veterinary Medicine with an emphasis in public health and translational medicine. She plans to use her training to help address the questions and challenges facing One Health due to emerging and zoonotic infectious diseases. When she is not busy learning how to save all things furry and playing with test tubes, Lydia can be found either freestyle cooking for her friends and family or binge watching Netflix with her rescue pup, Luna. More from Lydia Anderson.

Lydia Anderson is a Dual DVM-PhD graduate student at the University of Georgia. Since completing her PhD in Infectious Diseases, she has been working on her DVM at the College of Veterinary Medicine with an emphasis in public health and translational medicine. She plans to use her training to help address the questions and challenges facing One Health due to emerging and zoonotic infectious diseases. When she is not busy learning how to save all things furry and playing with test tubes, Lydia can be found either freestyle cooking for her friends and family or binge watching Netflix with her rescue pup, Luna. More from Lydia Anderson.