You wake up one morning with a sore throat and a runny nose. Let's say this goes on for a couple of days; you go to a doctor and discover you have a bacterial infection. You are prescribed antibiotics and after a couple of days of taking them, you start feeling better. Now imagine another scenario in which you take the antibiotics, but your symptoms continue to worsen. In this alternate scenario, you are suffering from an antibiotic resistant bacterial infection.

While there have been other posts on antibiotic resistance explaining the science behind the phenomenon, this post discusses the outbreak of an antibiotic resistant typhoid infection in Pakistan. The ensuing difficulties with responding to the crisis highlight the importance of effective science communication in helping us combat antibiotic resistance.

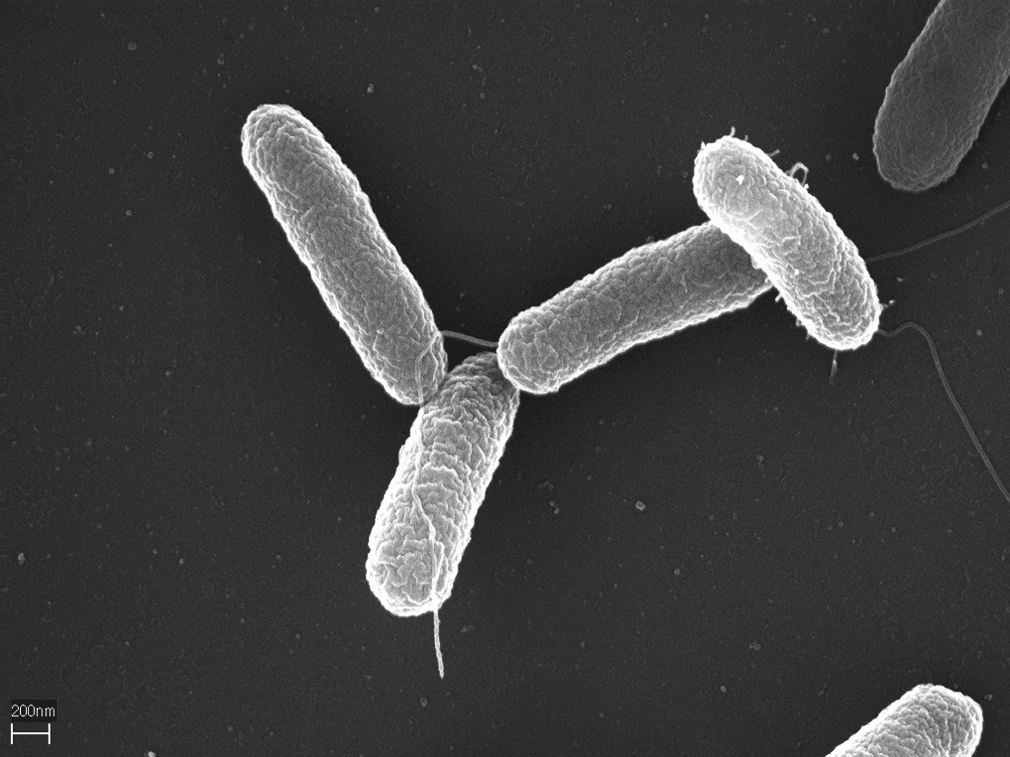

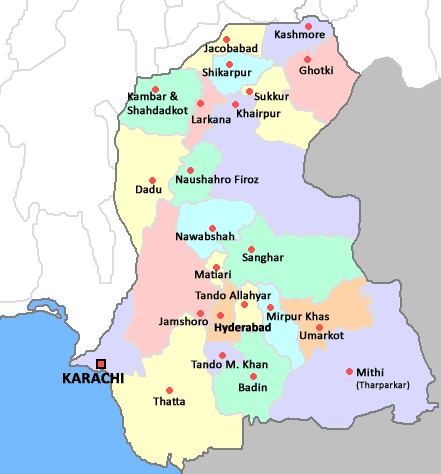

In November 2016, a new form of Salmonella Typhi, or typhoid, was discovered in Hyderabad, Pakistan. The strain, labeled XDR, was resistant to all but one antibiotic that had been used to treat typhoid in the past. The XDR strain mostly affected lower-income families unable to afford clean water, as the disease spread through contaminated sewage lines. The demographic affected by this issue faced several problems; not only did these families have to deal with a nearly incurable disease but they had to do so while also lacking the basic human rights to clean water and an adequate healthcare system.

In response, the local government tried to introduce a vaccination program in the affected areas in the southern city of Hyderabad to prevent spread of the disease, but multiple people refused to vaccinate their children due to the spread of misinformation about the vaccine. This compromised herd immunity, which requires that a sizeable majority of the population be vaccinated in order to restrict the spread of a disease.

As antibiotic resistance increases due to overuse of antibiotics, our only defense against the rise of these superbugs is widespread vaccination. Unfortunately, in Pakistan's case, the resistance and/or refusal to vaccinate was rooted in rumors that these vaccines had been poisoned as they came from India, a country with long standing political issues with Pakistan.

The above mentioned example stresses a real need for effective science communication to combat political narratives that come in the way of public health initiatives. Often those directly impacted by science have the least understanding of the process. The opaque nature of the scientific process in the eyes of people in these communities allows for doubt to creep in, providing fertile ground for those with vested interests. In this particular case, a campaign to better explain where the vaccines come from, who develops them, and independent verification from trusted organizations within Pakistan, could allow for some of this doubt to be lifted and may lead to increased rates of vaccination.

The XDR case in Pakistan is just one example, but similar problems can be seen in numerous public health issues. A better understanding of the science around us will help us link it to our day to day lives, increasing trust in the institution of science and allowing us to solve the myriad of issues the world faces today.

About the author:

|

Zaka Asif is a first year doctoral student rotation through different labs in the ILS program. When I am not working in my lab, I can be found driving around, watching/playing soccer or cricket, playing pool, cooking or just lazying around in bed. More from Zaka Asif. |