As humans, we sometimes eat some pretty weird things. (Rocky Mountain oysters, anybody?) But no matter how adventurous an eater you are, we typically draw the line once food starts to decompose. There is one animal, however, that thrives on a repulsive diet of death and decay.

Vultures are obligate scavengers. Unlike other carnivores, they almost exclusively eat animals that are already dead, and often well into decomposition. Since many wild animals ultimately succumb to a variety of infectious diseases, it is remarkable that vultures rarely contract foodborne illnesses. These birds of prey have several traits adapted to their diet, including an extremely acidic stomach to obliterate parasites. Recently, researchers identified another compelling adaptation – the vulture microbiome.

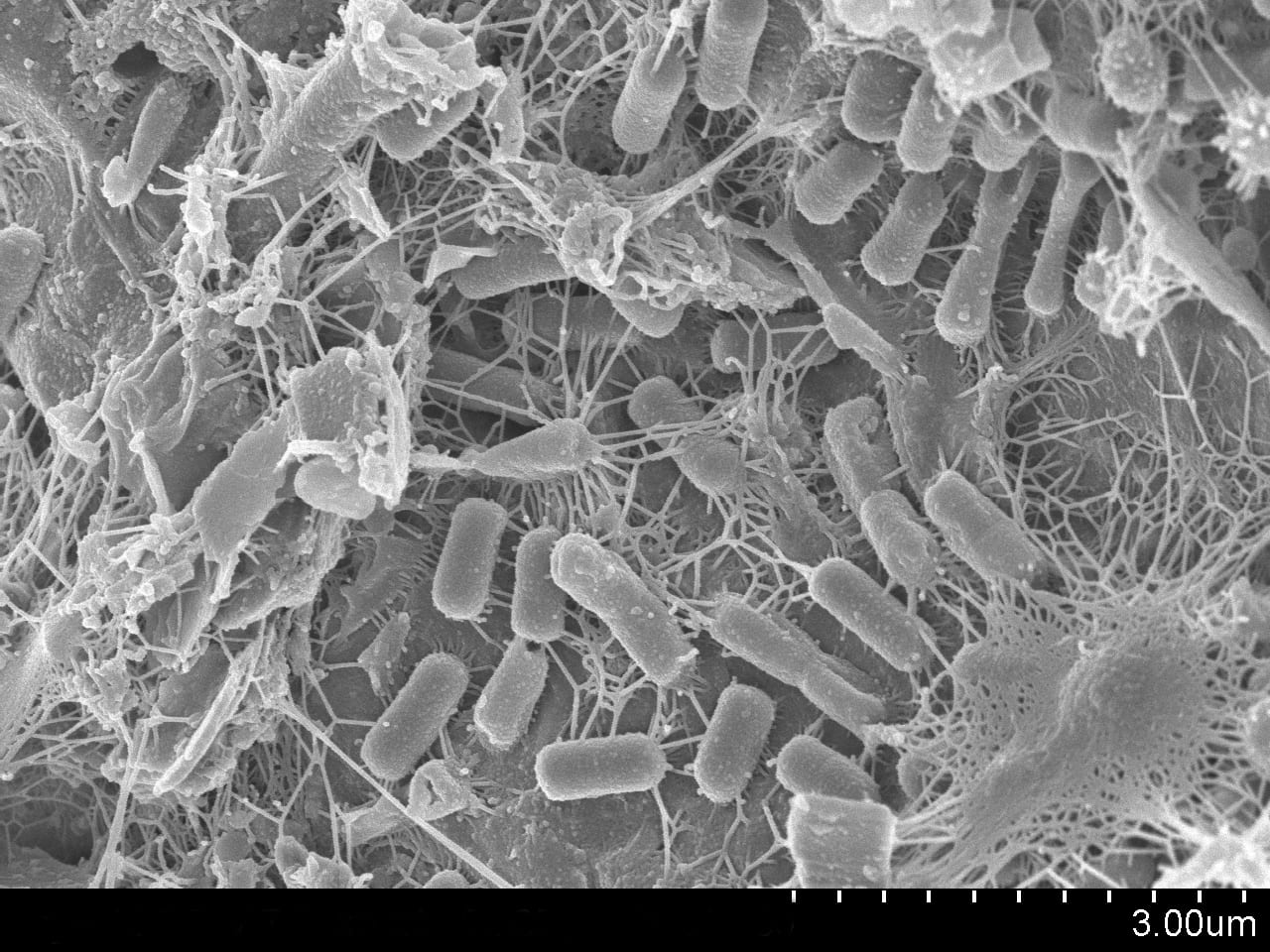

Microbiome research explores the diversity and abundance of microbes – bacteria and other tiny organisms – in an environment. From these studies, we have learned that bacteria occupy the gastrointestinal tract, or gut, of animals in staggering numbers. For context, at this moment there are as many microbes living inside of you as there are cells in your entire body!

Believe it or not, that's a good thing. Animals have co-evolved with their gut microbes in a complex form of symbiosis. The bacteria benefit by having a regular source of food from meals ingested by their host; in exchange, they break down molecules into usable calories and synthesize essential compounds like vitamins. The composition of the gut microbiome can vary significantly between species, or even individuals. Nevertheless, we are beginning to identify correlations between a “healthy†microbiome and overall health.

So how does the microbiome relate to our friend, the vulture? For that, we need to get morbid and talk about what happens after death. During an animal's lifetime, its microbial load – the number and composition of microbes – is restrained by the immune system. However, shortly after bodily functions cease, these safeguards fail and microbial populations explode, facilitating the process of decomposition.

Some of the most active bacteria during decomposition include Staphylococcus, Clostridium, and Fusobacterium species. You may have heard of a couple of these, almost certainly in relation to dangerous infections. This is where microbes are tricky – most are generally harmless, but left unchecked they can rapidly replicate, generate toxins, and cause disease. This is precisely why many animals have an aversion to rotting food; it is a sure sign of dangerously high microbial activity.

So why don’t vultures get sick from consuming these bacteria? To understand how these birds are affected by the increased microbial loads inherent to their diet, researchers sequenced the microbiome of the vulture hindgut, which is anatomically comparable to the human colon. They found that the hindgut contains a surprisingly low diversity of microbes, averaging 76 species per bird; for comparison, the human colon averages ~160 distinct species of microbes. What is shocking is that the two predominant bacteria are Clostridium and Fusobacterium, the same microbes that are associated with decomposition!

Many Clostridium species produce dangerous toxins, and Fusobacterium is sometimes associated with flesh-eating disease. Finding either of these in high abundance in a human gut would mean that person is extremely ill. However, this is apparently a healthy microbiome for a vulture! Based on their prevalence, there is clearly a high degree of selection for those species – in other words, a vulture's gut must have the ideal conditions to make those particular bacteria happy enough to permanently move in. Perhaps it's the all-you-can-eat roadkill buffet?

In turn, those microbial species occupy the same niche as the other pathogens in the vulture’s next meal, meaning there is no vacancy for anyone else to move in and establish an infection. In an ironic twist, it seems that these toxic bacteria may protect their host from getting sick! It is not clear exactly how the vultures tolerate the high abundance of these bacteria. They may have evolved a greater immunity to toxins; alternatively, they may have strategies to ensure only non-virulent strains are able to become established.

In any case, this is a fascinating example of how a host and its microbes have co-evolved and adapted to a specific lifestyle. Things get infinitely more complicated for us with diets, lifestyles, and microbiomes that are much more variable than a vulture's. However, understanding host-microbe interactions will inevitably play a major role in how we approach health and disease moving forward. What these studies definitely illustrate is that there's no such thing as a universally “bad†microbe. As the saying goes, one bird's meat is another man's poison.

Featured Image courtesy of Mark Kent via Flickr.

Jennifer Kurasz is a graduate student in the Department of Microbiology at UGA, where she studies the regulation of RNA repair mechanisms in Salmonella. When not in the lab, she prefers to be mediocre at many hobbies rather than settle on one. She greatly enjoys her women's weightlifting group, cooking, painting, meditation, craft beer, and any activity that gets her outdoors. She can be contacted at jennifer.kurasz25@uga.edu. More from Jennifer Kurasz.

Jennifer Kurasz is a graduate student in the Department of Microbiology at UGA, where she studies the regulation of RNA repair mechanisms in Salmonella. When not in the lab, she prefers to be mediocre at many hobbies rather than settle on one. She greatly enjoys her women's weightlifting group, cooking, painting, meditation, craft beer, and any activity that gets her outdoors. She can be contacted at jennifer.kurasz25@uga.edu. More from Jennifer Kurasz.