The “salt wars” have been raging for decades, with medical science still embroiled over whether there is a direct link between sodium consumption and heart disease. Last year, a group of researchers published an editorial in an American Heart Association journal proposing a way to finally get to the bottom of this; in the process, they reawakened an ethical controversy.

The experiment is simple. Take two groups of people; one exclusively eats a low-sodium diet while the other eats as usual. After x amount of time, subjects undergo tests to determine if there is evidence of heart disease. However, long-term dietary studies are notoriously difficult to pull off. Even if researchers could find volunteers to forego eating salty, flavorful food for several years, there is little they can do to ensure that subjects don’t cheat. Ideally, they would need a closed population of participants whose diets and health can be continuously monitored for an extended period of time. Enter the American prison system.

The editorial advocates for using inmates as experimental subjects. Logistically, it makes sense. The environment is definitely controlled, the study is noninvasive, and it’s important to note that participation would be voluntary. But many have balked at this idea, recalling a time when prisoners and other vulnerable groups were routinely exploited “for science.” These clashing contexts raise the question: is this ethical?

A history of maltreatment

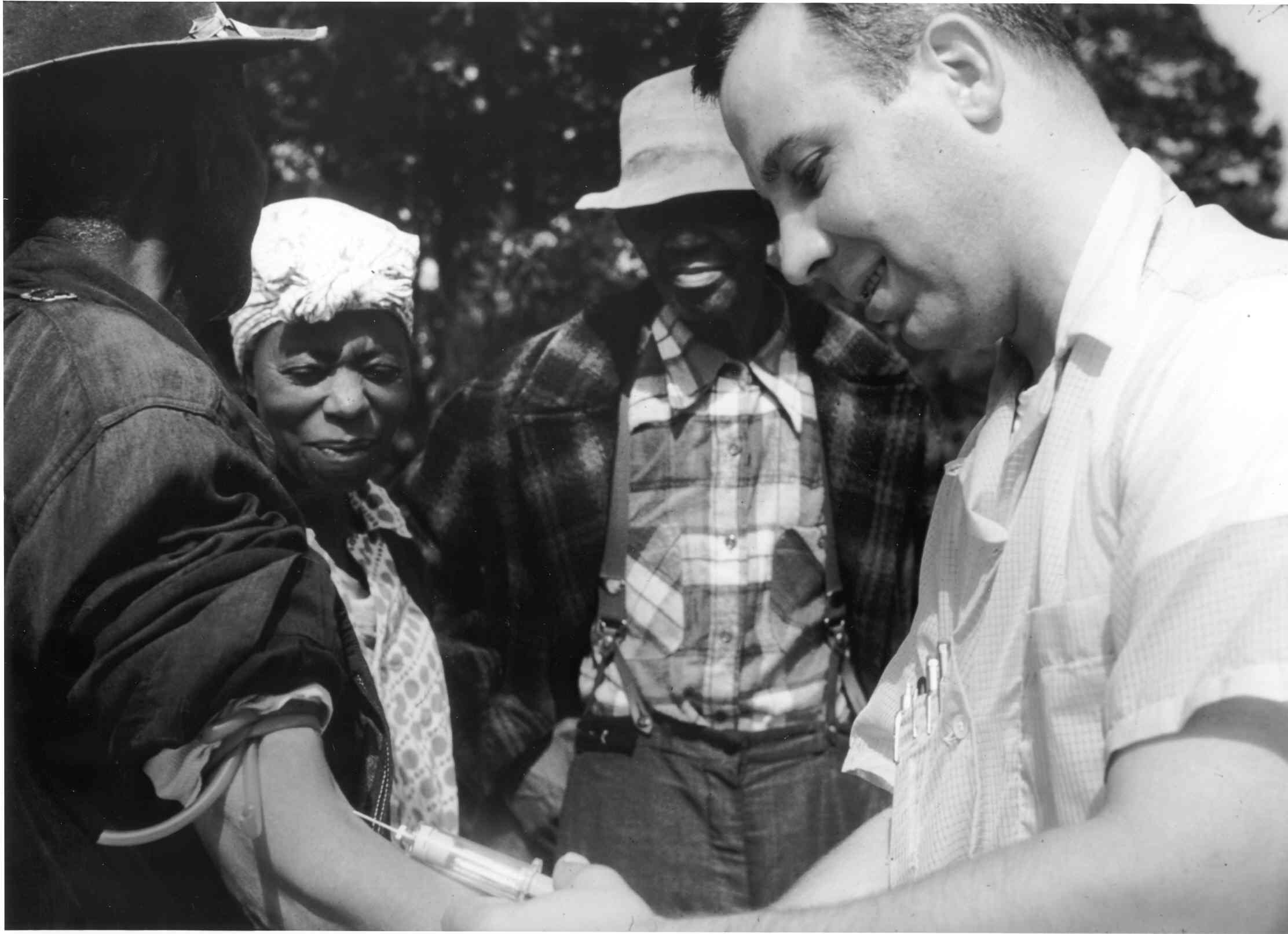

We certainly cannot pretend like there is no precedent for clinicians abusing the prison system. From as recently as the mid-20th century, we have records of healthy prisoners being purposely infected with malaria, viral hepatitis, or even live cancer cells. And it didn't end with infection studies; prisoners were also given experimental organ transplants, radioactive injections, and had their skin treated with hazardous chemicals. Subjects were sometimes coerced into participating by the suggestion that they would be granted parole. Many were outright lied to about the risks involved; some even died after being promised they would suffer no ill effects.

Then the nation found out about the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, and public outcry was fierce regarding the unjust treatment of human subjects. It ultimately led to the issuance of the Belmont Report, which established ethical standards for maintaining the rights of all human subjects. These include tenets such as informed consent, voluntary participation, and that the benefits of participating in a study should outweigh the risks.

Protecting vulnerable populations

Even with these standards in place, some classes of people are still particularly vulnerable and in need of extra protection. These include prisoners, people with mental disabilities, the extremely impoverished, and children. A group is considered vulnerable if its members have diminished free will or capacity to give informed consent. For these people, the potential for being manipulated, even if it’s unintentional, is much greater.

Thus, additional conditions must be met in order to include prisoners in studies. Only four classes of research are currently permitted under federal regulations:

1) causes, effects, and processes of incarceration or criminal behavior;

2) assessment of prisons as institutions;

3) conditions that specifically affect prisoners as a class; and

4) practices that are likely to improve health or well-being.

Due to these criteria, almost all federally funded research in prisons is for the purpose of directly addressing prison issues.

The ethical dilemma

Based on these criteria, would the aforementioned prison sodium study be ethical? One can argue that it is likely to improve inmates’ health. But governing boards are usually wary of approving prison research based on this criterion alone, because intentions still matter. Results from the dietary sodium study would primarily affect patients out in the world; it’s somewhat incidental that it may also help inmates. Does this then set a precedence that prisoners should take on the research burden for other clinical studies whenever it’s most convenient?

For their part, inmates who were surveyed had generally favorable attitudes toward research in prisons. Sometimes taking part in studies even grants them access to advanced healthcare and treatments beyond what an average person would normally receive, so barring them from participating could be unjust in its own right.

As in any good ethical debate, you can argue both sides until you drop. Fortunately, there are now independent groups of experts and peers whose job it is to deliberate over such matters. It remains to be seen whether this particular study will be given the green light; until then, the salt wars rage on.

Featured image credit: Ichigo121212 via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under: Pixabay License.

Jennifer Kurasz is a graduate student in the Department of Microbiology at UGA, where she studies the regulation of RNA repair mechanisms in Salmonella. When not in the lab, she prefers to be mediocre at many hobbies rather than settle on one. She greatly enjoys her women's weightlifting group, cooking, painting, meditation, craft beer, and any activity that gets her outdoors. She can be contacted at jennifer.kurasz25@uga.edu. More from Jennifer Kurasz.

Jennifer Kurasz is a graduate student in the Department of Microbiology at UGA, where she studies the regulation of RNA repair mechanisms in Salmonella. When not in the lab, she prefers to be mediocre at many hobbies rather than settle on one. She greatly enjoys her women's weightlifting group, cooking, painting, meditation, craft beer, and any activity that gets her outdoors. She can be contacted at jennifer.kurasz25@uga.edu. More from Jennifer Kurasz.