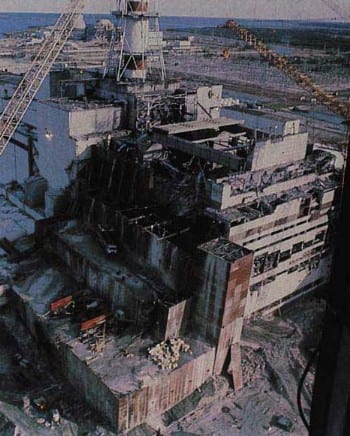

On April 26, 1986, in the city of Pripyat, Ukraine, a group of engineers working on the No. 4 Reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant accidentally caused one of the greatest environmental disasters known to mankind. 50 tons of radioactive material were released into the atmosphere and dozens of lives were lost. Pripyat was evacuated and left as a radioactive wasteland.

Accidents like the one at Chernobyl leave a pretty big mess, and though humanity is often very irresponsible when it comes to taking care of the planet, the weight on our collective conscience after a mishandling of nuclear power like this inspires action. So how do you clean up after a nuclear incident? Why, you plant sunflowers of course!

Okay, full disclosure, planting sunflowers will not suddenly solve all of your nuclear nightmares, but the flowers do something pretty cool to help clean up the environment. The common sunflower (Helianthus annuus) is a hyperaccumulator of dangerous heavy metals. Like many other hyperaccumulating plants, sunflowers extract metal compounds from deep in the soil and transport them into the stem, leaves and, flower head. In a process called phytoremediation, hyperaccumulating plants are used to clean up environmental contamination.

Well, it just so happens that sunflowers are particularly adept at extracting radioactive metals, like the cesium-137 and strontium-90 found at Chernobyl. After the Chernobyl disaster fields of sunflowers were planted to harvest these radioactive metals from the ground, and when the sunflowers were all grown up, they were harvested and safely disposed of through pyrolysis. This process burns off all of the organic carbon in the plant while leaving the radioactive metals behind. These metals are then vitrified into pyrex glass and stored in a shielded container underground.

Thankfully, there's not a nuclear disaster every week that needs cleaning up, but sunflowers are more than just good at cleaning up radioactive metals. Sunflowers are also hyperaccumulators of some of the most common metal pollutants on our planet, such as cadmium, nickel, zinc, and lead. Sunflowers, along with Indian mustard (another hyperaccumulator) were used to clean up soils contaminated with these metals near a Chrysler automotive production facility in Detroit. The use of hyperaccumulating plants for this project, which was massive in scale, cut the cost of cleaning those soils by more than half when compared to more conventional methods.

While there are many outstanding benefits to using sunflowers for phytoremediation, they aren't perfect. Firstly, sunflowers don't accumulate all metals equally. Metals like arsenic and mercury, among some others, are not taken up by the plant. This means that sunflowers alone can't completely clean up contaminated sites. However, other hyperaccumulators have different and sometimes even complementary metal preferences. So planting multiple hyperaccumulator species, like at the Chrysler automotive site in the example above, is one way to get around this problem.

Another issue is that not all sunflowers have the capability to accumulate metals. Individuals within the common sunflower species H. annuus have substantial variation in the ability to accumulate metals. This is a very serious concern. In 2013, after a tsunami hit the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan, fields of sunflower were planted to clean up radioactive metals. Unfortunately, planting sunflowers near Fukushima was much less successful than it was around Chernobyl. Why? They unknowingly planted the wrong variety of sunflower, one that wasn't a good hyperaccumulator. Right now, researchers don't fully understand why some can and others can't. Understanding this is critical if we want to successfully use sunflowers for phytoremediation in the future.

Despite these issues, there still remains massive potential to use sunflowers effectively for phytoremediation. The great success of planting sunflowers around Chernobyl is proof of this. Researchers now are attempting to better understand the biology of hyperaccumulating plants and use that knowledge to improve phytoremediation technologies. With a little breeding, sunflowers of the future will be even more effective at extracting metals from the ground. For now though, it's worth appreciating that sunflowers are for more than just oilseed or decoration, they are powerful tools we can use to clean up nuclear waste and help save the planet!

About the Author

Max Barnhart is a PhD studying the evolution of heat stress resistance in sunflowers at the University of Georgia. He is also the current Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Athens Science Observer. Growing up in Buffalo, NY he is a diehard fan of the Bills and Sabres and is also an avid practitioner of martial arts, holding a 2nd degree black belt in Taekwondo. You can contact Max at maxbarnhart@uga.edu or @MaxHBarnhart.

- Max Barnharthttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/max-barnhart/October 21, 2021

- Max Barnharthttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/max-barnhart/November 11, 2020

- Max Barnharthttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/max-barnhart/October 19, 2019

- Max Barnharthttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/max-barnhart/October 15, 2019