In 2015, Zika virus resulted in a global public health emergency. The epidemic caused severe brain defects in thousands of Brazilian newborns after the virus was transmitted to pregnant mothers via infected mosquitoes. The rapid emergence of disease caught everyone by surprise, and with little understanding of the virus pathogenesis it left scientists unprepared to prevent and treat disease in affected infants.

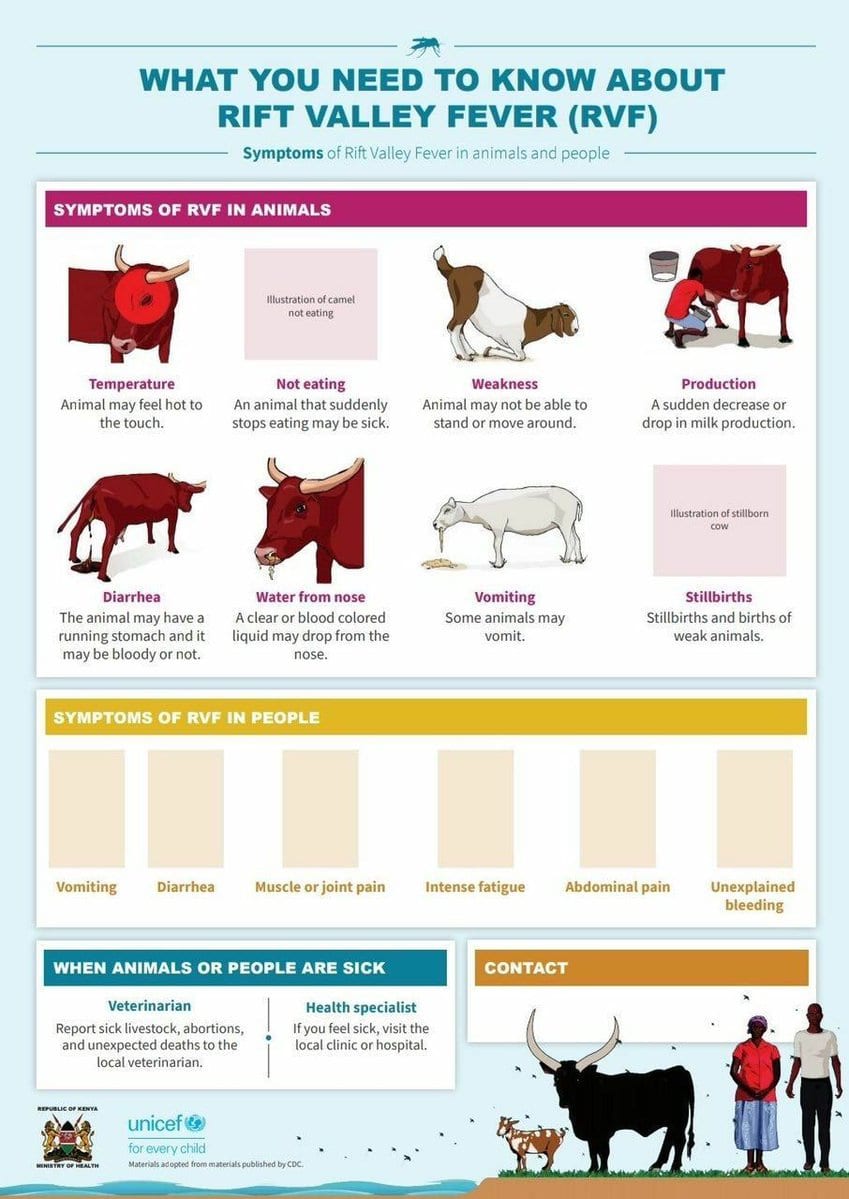

Like Zika, infection with RVF virus can go unnoticed during pregnancy and cause catastrophic, often lethal, damage to the fetus. RVF was first reported in livestock by veterinary officers in Kenya's Rift Valley in the early 1910s. RVF viral disease is most commonly observed in cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, and camels, with the ability to infect and cause illness in humans. Outbreaks of RVF can have major societal impacts, including significant economic losses and trade reductions. In an effort to prevent history from repeating itself, scientists are now working to develop effective vaccines for Rift Valley fever (RVF).

Different types of vaccines for veterinary use are available to prevent RVF; however, they all have their drawbacks. The killed vaccines are not practical in routine animal field vaccination because of the need for multiple injections. Live vaccines only require a single injection, but because this is still a live virus it is known to cause birth defects and abortions in sheep and only provide a low level of protection in cattle. A weakened version of the virus has been developed to create a live-attenuated Clone 13 viral vaccine, which was recently licensed in South Africa with more than 19 million doses already used in the field. The Clone 13 vaccine performed well in controlled animal trials; however, a major hurdle for vaccine efficacy comes down to cold chain. A recent study demonstrated that the Clone 13 virus is stable for more than 12 months when stored at 4℃, but the virus is unstable at temperatures above 22℃. This temperature storage issue is not unique to RVF vaccines, and remains an ongoing battle when vaccinating in hot climates served by poorly developed transport networks.

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers RVF a potential public health emergency and calls for accelerated research and development due to the lack of approved treatments for animals or humans. Although this mosquito-borne, zoonotic disease has been reported only in Africa and the Middle East, the mosquito that transmits the virus also ranges from Europe to the Americas. From 2000 to 2018, 4830 cases of severe RVF in humans were reported to the WHO, including 967 related deaths. Epidemiology in human pregnancy is severely lacking, but among herds of livestock, RVF outbreaks lead to widespread miscarriage and stillbirth affecting more than 90% of pregnant livestock.

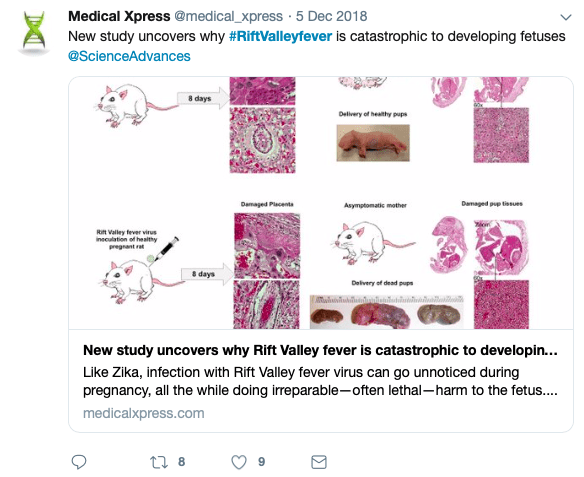

In a recent study, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh Center for Vaccine Research discovered how the virus targets the placenta. These studies provide important information for the development of human vaccine. The researchers showed that in pregnant rats with no signs of clinical disease, RVF virus is vertically transmitted from mother to fetus through the placenta, resulting in a high rate of stillbirths.

The group also exposed human tissue samples obtained from pregnant women in their second trimester to RVF virus, and then monitored viral levels every 12 hours. They found high virus levels in the placenta, including in a layer of cells called the syncytiotrophoblast. This makes up the outer layer of cells that actively invades the uterine wall and establishes an interface between maternal blood and embryonic fluid, allowing exchange of material between the mother and the embryo. A growing body of evidence suggests that the unique structure of the syncytiotrophoblast facilitates the placenta's protective function.

But, here is the real kicker. The syncytiotrophoblast is typically resistant to infection by diverse pathogens, including Zika virus, raising a major red flag that RVF virus may be an even more frightening threat. Essentially RVF virus takes the expressway to get into the placenta as opposed to the windy back roads of its Zika virus counterpart.

While having these research models in place is an important step for combating RVF, the path towards a safe and efficacious vaccine for humans is still under construction. Ultimately, the prevention of a RVF epidemic will require a One Health approach assessing the interaction between the environment, animal health, and human health to inform risk mitigation and prevention measures.

Featured image: Image by Wellcome Trust via Twitter

Lydia Anderson is a Dual DVM-Ph.D. graduate student at the University of Georgia and currently serves as an Associate Editor for Athens Science Observer. Since completing her Ph.D. in Infectious Diseases, she has been working on her DVM at the College of Veterinary Medicine with an emphasis in public health and translational medicine. She plans to use her training to help address the questions and challenges facing One Health due to emerging and zoonotic infectious diseases. When she is not busy learning how to save all things furry and playing with test tubes, Lydia can be found either freestyle cooking for her friends and family or binge watching Netflix with her rescue pup, Luna. More from Lydia Anderson.

Lydia Anderson is a Dual DVM-Ph.D. graduate student at the University of Georgia and currently serves as an Associate Editor for Athens Science Observer. Since completing her Ph.D. in Infectious Diseases, she has been working on her DVM at the College of Veterinary Medicine with an emphasis in public health and translational medicine. She plans to use her training to help address the questions and challenges facing One Health due to emerging and zoonotic infectious diseases. When she is not busy learning how to save all things furry and playing with test tubes, Lydia can be found either freestyle cooking for her friends and family or binge watching Netflix with her rescue pup, Luna. More from Lydia Anderson.