Have you ever dreamed of traveling the world with no need for a translator and then realized you would have to actually learn a new language? Have you tried to learn, only to give up after the intro course? Has the little green owl on your Duolingo app stopped giving you reminders because “they don't seem to be working?†Well, it's time to stop putting off those linguistic goals from your New Year's resolution list. Learning a new language not only helps you embrace a new country and its culture, but it may offer cognitive and neuroprotective benefits, as well.

Bilingualism in the US has been steadily increasing since 1980. Though these numbers are commonly attributed to immigration, native English speakers' improved interest in foreign languages has also added to the bump. In early days bilingualism was seen as a distracting disadvantage to traditional learning. Since then, it has been proven that multilingualism actually facilitates learning. Bilingual individuals are better at switching tasks and filtering out unnecessary stimuli when focused. This happens because any stimuli requiring response triggers the engagement of multiple parts of the brain, regardless of what language the person is currently using. A Spanish-English bilingual might see the mental cue of a filled glass and think “water†and “agua†at the same time. So, how does the brain manage this task-juggling feat? Easy– by rewiring!

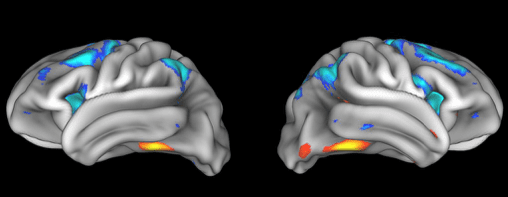

Bilingualism changes functional plasticity in the brain

In early days, scientists believed bilingualism led to learning impairments. More recently, studies found that when tasked with object-identifying tasks, participants who spoke more than one language had slower response times. However, when confronted with non-linguistic challenges, like categorizing the objects, bilinguals showed no difference or delay and, in some tasks, even outperformed monolinguals by filtering unnecessary information. This is because bilinguals are more efficient at using their anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and left anterior parietal cortex (APC), areas of the brain commonly associated with language control and non-verbal conflict. In fact, bilinguals have higher volumes of gray matter (where the brain cells live) in these areas when compared to monolinguals.

It is not only the brain's gray matter that is changed with second language acquisition, but white matter (which connects the nerve cells), as well. A study using a technique called fractional anisotropy (which measures diffusion of fluid to study the makeup of the brain) characterized the structural connections of four white matter areas in bilinguals and monolinguals. They found that the number of languages, as well as the time they have spoken multiple languages for, induced change in the brain's neuronal connections. This change led to a difference in area density and topography of the brain's white matter.

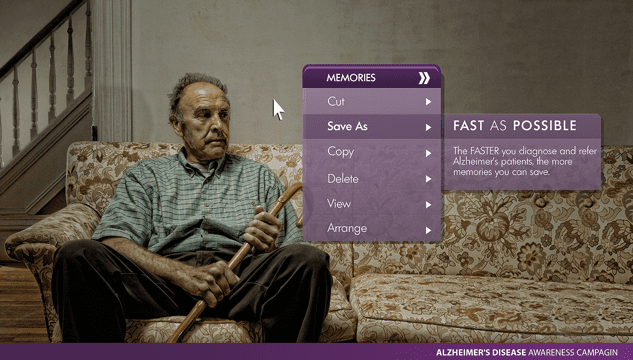

Languages as brain armor

Bilingualism changes how your brain is structured. This rewiring may offer extra perks as you age. Studies on diseases like dementia and Alzheimer's indicate that people who learn a second language may be able to delay disease onset when compared to single-language persons. In general, patients who knew two or more languages exhibited Alzheimer's symptoms about five years later than monolinguals. This is due to a phenomenon known as the “cognitive reserveâ€, or the protection of neurological functions. This area of research has gained notoriety in recent times in light of the steadily increasing mean age of the world population and the necessity to improve late-stage quality of life. The mental act of switching between languages triggers increased activity and strengthens the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Basically, it gives the area responsible for problem-solving, task-switching and filtering unnecessary stimuli a much-needed workout.

Have you missed your window?

You might be thinking, “This is great and all, but learning a new language is hard. Plus, I'm too old to get all those brain benefits.†Yes, learning new things is hard. And, sure, it is easier to learn a second language during your childhood, but that doesn't mean you can't learn. More importantly, science says you're not too late to gain all those sweet brain benefits!

Bilingual people can be broken down into three subcategories: compound (early, simultaneous learners), coordinate (early, sequential learners), and subordinate bilinguals (late learners). Late learners still have increased brain activity over their single-language peers. And what's more they also have delayed Alzheimer's and dementia symptom onset. As time of learning and use of a second language increases, so do the neurological benefits. So, whether you want to travel the world with nothing holding you back, safeguard your brain health, or just get better at multitasking, learning a second language can be your ticket to success.

About the Author

Jennifer McFaline-Figueroa is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, where she studies strategies for skeletal muscle rehabilitation and regeneration following injury or disease. Her interests include mitochondrial physiology, orthopedics, and dogs. Outside of lab, Jen enjoys reading, listening to true crime podcasts, and griping about the cold like a true Puerto Rico native. You can reach Jen at jm08293@uga.edu or follow her on Twitter @jey_at_lab.

About the Author

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 17, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 12, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/April 3, 2020

- athenssciencecafehttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/athenssciencecafe/March 30, 2020