The US Atlantic coast is a dynamic, living landscape. Georgia in particular displays a picturesque mosaic of barrier islands, salt marsh meadows, maritime forests, brackish marsh and river networks snaking up the Coastal Plain. Together, coastal habitats form a dynamic ecosystem capable of protecting the coastline, storing carbon, filtering water and providing coastal regions with valuable fisheries.

The last hundred years, however, have set the stage for unsettling trends in the rate at which coastal areas are changing. As the earth warms and glaciers melt into the ocean, scientists are predicting an increase in sea level between 3 and 11 feet for the Georgia coast by the end of the century. While this “sea-level rise†may not sound significant, a minimum of 12,500 homes, 350 miles of road and 278 square miles of the Georgia coast will face catastrophic flooding. Similar flooding scenarios are expected to play out along the entirety of the eastern US coast. Notably, it's not just the rising sea-level that's an issue, but also land sinking. Much of this sinking is the natural result of post-ice age glacial rebound, which is one of the main contributors to sea level rise in coastal Georgia.

The effects of rising sea levels aren't always as visible as flooding. Increased rates of saltwater intrusion into groundwater and low-lying areas is also a growing problem which can lead to even faster soil breakdown and further loss of elevation. One major example of this process is being observed in the Florida everglades. Another phenomenon resulting from this saltwater intrusion is occurring on a large scale in coastal trees. As saltwater pushes inland, salt-intolerant hardwood trees are dying. From the roots up, coastal tree communities are transitioning into “ghost forests.â€

Ghost forests do not pop up overnight, but they are becoming increasingly prevalent. Tree death is a gradual process, normally taking years to decades, but the increasing frequency of extreme weather events like storms and drought can accelerate forest loss. Hardwood species such as oaks and tupelo are usually the first to go, followed by more salt-tolerant species like sweet gum, red cedar and loblolly pine. Eventually, entire landscapes will transition from forest to marsh, and perhaps in time to open water.

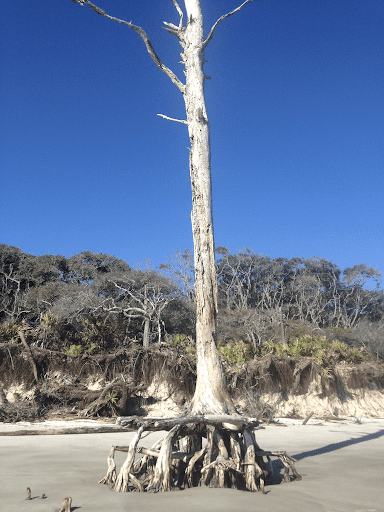

A similar phenomenon has been noted on barrier islands, like those spanning the coastline of Georgia and South Carolina. These islands are shaped by the movement of wind, ocean currents and sediment. Typically, sediment gets stripped from the northern end of barrier islands and is then deposited along the southern end, forming a new beach. This process of sand-sharing can give rise to “skeleton†or “boneyard†forests along the eroding beaches.

As forests succumb to the sea, the skeletons of maritime forests help to stabilize eroded beaches. They can even be beautiful, serving as popular tourist attractions. However, even though skeleton forests may represent a natural part of Georgia's barrier island life cycle, the increasing rate of land loss due to the combination of rising sea levels, human development and extreme weather is faster than some islands can keep up with.

Ghost forests can be viewed as a natural response to changing environmental conditions. Emergent marshes are better able to store carbon and keep up with sea level rise than forested areas because of their ability to capture sediment and vertically accrete. However, the overall area of marsh land is declining faster than it can accrue due to sea level rise. Marsh expansion also depends on the availability of natural land at higher elevations to compensate as lower elevation land becomes completely submerged. This ability is limited by human activity when coastal communities build homes and install hard structures like sea walls to prevent beach erosion.

Overall, the growing presence of ghost forests from Louisiana to Canada is a worrisome indicator of a rapidly changing coast, and researchers are taking notice. Within the Georgia Coastal Ecosystems Long Term Ecological Research Program (GCE LTER), a project has been initiated to measure the response of trees along the Altamaha river to hurricanes. So far 45 trees are being repeatedly surveyed as an indicator of forest health as storm events increase and salt water pushes further up into rivers.

Compared with the more developed coastline along the Northeastern US, Georgia is praised for its roughly 100 miles of pristine coast. Unfortunately, sea level rise is both a global and a local problem that we'll all have to face, and ghost forests, although captivating, are a haunting reminder of what's at stake.

About the Author

Rebecca Atkins is a Ph.D. student in the Odum School of Ecology studying. She is passionate about coastal ecology and is currently studying the effects of temperature on snail populations across Atlantic US salt marshes. In her spare time, she pursues art, weight lifting and drinking copious cups of local coffee. You can email her at Atkinsr@uga.edu or follower her @RL_Atkins

- Rebecca Atkinshttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/rebecca-atkins/March 25, 2021

- Rebecca Atkinshttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/rebecca-atkins/February 17, 2021

- Rebecca Atkinshttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/rebecca-atkins/December 4, 2019

- Rebecca Atkinshttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/rebecca-atkins/June 27, 2019