How many times has this happened to you before? You walk into a room–it could be one you've stepped foot in a dozen times that day, or never at all– and hesitate by the doorway. There is something about that space that is nagging at the back of your mind. You decide that, somehow, you have lived through this moment before or you've seen this room, exactly as it is arranged now, at this precise point in time. You likely know what the feeling is called, déjà vu, but what is it? And why does it happen?

What is déjà vu?

Déjà vu is a French term that translates as “already seenâ€. It was coined by philosopher Émile Boirac to describe the brief sensation of having already lived a novel moment. The majority of the population has had at least one episode of déjà vu in their life, with 60% of the population experiencing them regularly. These episodes can persist anywhere from ten to thirty seconds and have no damaging or lasting effects. The sensation of déjà vu comes from the combination of two different cognitive processes: the recognition of a particular event (knowing you've been there/seen that before), and the awareness that recognizing the event is incorrect (knowing you possibly couldn't have been there/seen that before). What's more interesting, though déjà vu is a very common phenomenon, its causes can vary depending on the individual.

An odd side effect

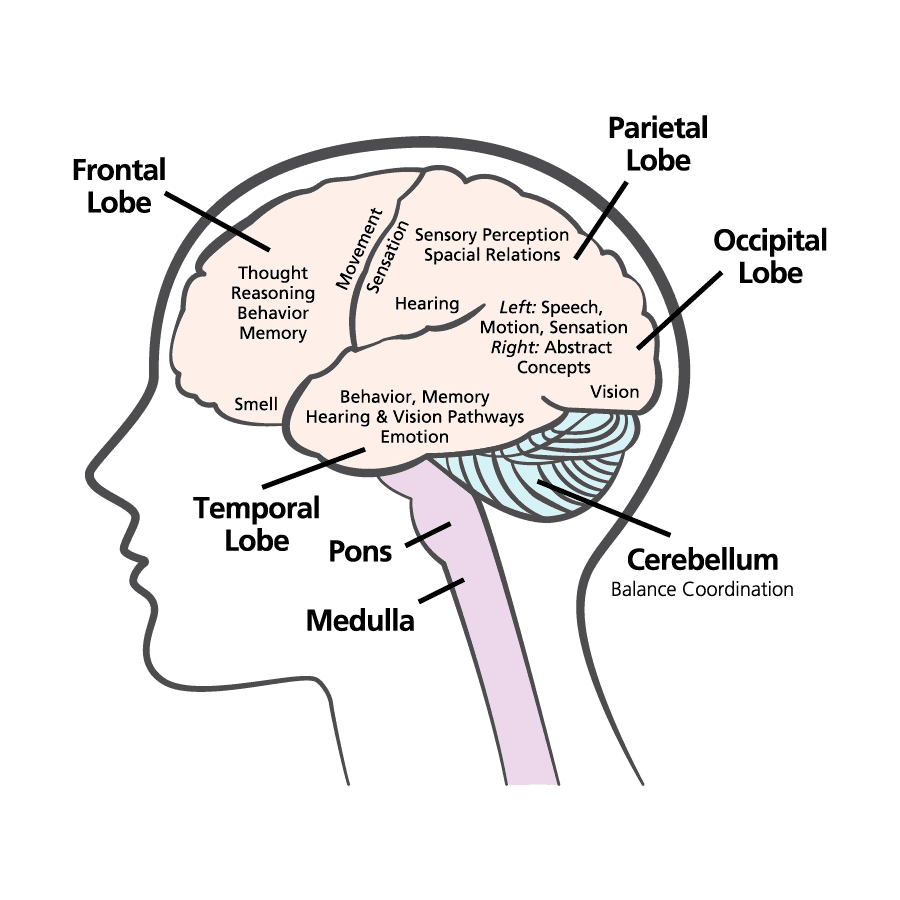

Instances of déjà vu are often associated with neurological or psychological conditions. However, regardless of whether the cause of déjà vu is benign or pathological, scientists agree that the areas of the brain involved are all found within the temporal lobe. These regions are in charge of processing sensory stimuli (everything you hear, see, smell, taste, and feel) and converting them into memories in the rhinal cortex. The rhinal cortex acts as a middle man–it helps take the information received by your senses and turn them into memories. Those memories can then be consciously recalled when needed. The more common an event is, the less rhinal processing it requires to be stored and retrieved. Certain conditions can affect this storage/retrieval process, suggesting that déjà vu could result from gaps in memory conversion in the rhinal cortex, like when you save several files in your computer to similar names and you have to open a few files before finding the right one.

The most common pathological cause of déjà vu is temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). TLE is a common form of focal epilepsy and can be subdivided by the severity of symptoms, going from momentary loss of awareness (simple partial seizure) to strong convulsions. Déjà vu often precedes epileptic episodes in the mildest form of TLE, simple partial seizures. It serves as an “aura†for oncoming episodes of epilepsy felt before the onset of more severe symptoms. This particular type of déjà vu differs from that of healthy individuals because the sense of familiarity is not connected to anything in the environment–they do not feel as if they've lived that moment or been in that place before. This distinction has led scientists to conclude that disease-associated and “normal†forms of déjà vu must have different causes.

A glitch in the matrix?

While there is certainly evidence linking it to disease, déjà vu is most often just a glitch in a completely healthy brain. Incidence is significantly higher in young adults (15-25 years of age) and in those with higher education, socioeconomic class, or who travel often. Additionally, déjà vu is also increased in subjects who are under significant stress or lacking sleep. This evidence had led scientists to think that déjà vu is a by-product of memory consolidation, the process of transforming short-term memory to long-term. Therefore, with increasing stimuli like enjoying movies, documentaries, and books, or decreased amount of time for processing, the frequency of episodes increases.

Probably the most fascinating fact about déjà vu is that brains of healthy individuals who experience the phenomenon are different from those who report no episodes. One particular study observed the volume of brain cells, or grey matter, in different regions of the temporal lobe in subjects with and without déjà vu experiences. People who report experiencing déjà vu episodes have a lower total volume of grey matter in memory-specific areas of temporal lobe compared to those who don't experience the phenomenon.

The brain is a magnificent machine capable of unimaginable wonders, but that doesn't mean it's perfect. In its quest for efficiency, it sometimes takes a few ill-advised shortcuts that can leave you feeling confused. So, next time you walk into a room and feel like you've lived that moment before, remember that it's the harmless side effect of a brain trying to juggle too many things at once. Take a moment to appreciate the complex process that brought on this phenomenon and maybe consider taking more naps.

About the Author

Ph.D. student in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at the University of Georgia, studying strategies for skeletal muscle rehabilitation and regeneration following injury or disease. Interests include mitochondrial physiology, orthopedics, and hugs. Outside of lab, I enjoy reading, listening to true crime podcasts, and griping about the cold like a true Puerto Rico native. You can reach me at jm08293@uga.edu or follow me on Twitter @jey_at_lab.