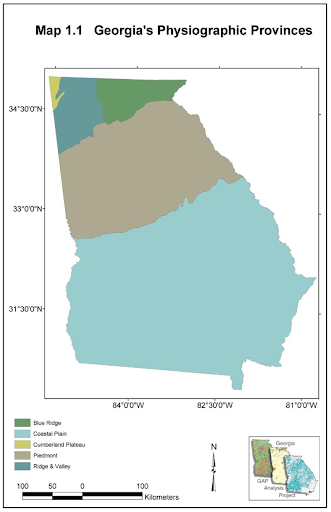

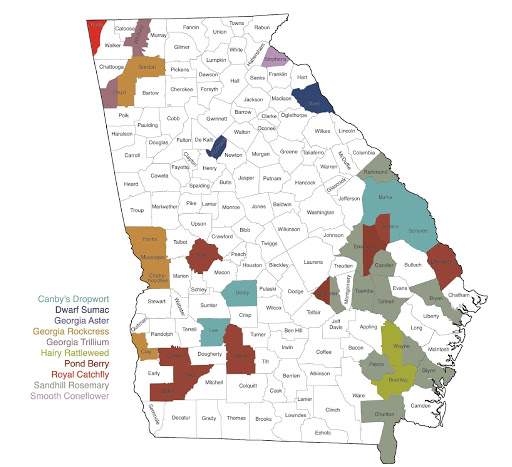

What ecosystem do you think about when you see the state of Georgia? Was it the sprawling forests you see on nearly every drive you make? If it was, this is likely because Georgia's land is nearly 70% forested and is one of the top states that contributes to the logging industry. Georgia is made up of 5 physiographic regions – the Cumberland Plateau, Ridge and Valley, Blue Ridge, Piedmont, and the Coastal Plains- which are home to unique ecosystems. The coastal plains are home to the Okefenokee Swamp. The Blue Ridge and Cumberland Plateau are home to the forested mountains where hikers trek. The Piedmont, however, is home to most of Georgia's population as well some of its most threatened ecosystems: granite outcrops and prairies. These ecosystems have long been overtaken by human development, invasive species, and hardwood forests. When the first settlers arrived here in Georgia, it was thought that the forests were dense but throughout them there were breaks in the trees where sprawling meadows were soaked in sun. These openings were later coined to be called “pocket prairies” which is the name grassland areas in Georgia hold today. The original breaks in tree density were thought to be produced by specific soil types, consistent wildfires, and large grazing animals such as elk and bison. Pocket prairies support hundreds of plant, insect, and animal species, but after several years of harsh farming and human development, those species have been rapidly declining in response to the depletion of habitat. This has led Georgia to have many endangered prairie plants such as: the smooth coneflower, Georgia aster, dwarf sumac, curly-heads, and many more. These species, much like many others, are also facing the threat of extinction because of loss of habitat, reduction in pollinators, and the overall impacts of climate change.

Credit to the State Botanical Garden of Georgia Science and Conservation Team and the Mimsie-Lanier Center for Native Plant Studies.

The State Botanic Garden of Georgia partnered with the University of Georgia (UGA) have been working tirelessly over the past few decades to protect and restore these delicate ecosystems. Most often we think the solution to reverse our impact on the land is to plant trees and lots of them, but when I spoke with Jennifer Ceska from the State Botanic Garden of Georgia working the Science and Conservation Team she states the importance of getting “the right plant in the right placeâ€. Planting trees in a prairie space would result in covering immense biodiversity that would be produced if the prairie plants were left to open to the sunshine rather than being overshadowed by towering hardwoods. While trees are important in sequestering carbon, their commitment to this takes at least 10 years to become substantial and stores their carbon in their wood. Prairie plants are mainly grass and wildflowers that have roots that extend over 4 meters into the ground which is where they store much of their biomass and carbon and they take only 1 or 2 years to establish themselves.

So, where are the pocket prairies in Georgia then? Well, there are not miles and miles of prairie like when you think of my home state of Nebraska, but only scattered across the state. Many of them are right here in Athens! The State Botanic Garden of Georgia's Science and Conservation Team has been working closely with many partners such as the Chattahoochee and Oconee Forest Services, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Georgia Power, and the Georgia Department of Transportation to establish pockets of prairies along rights-of-way areas like roads and powerlines. You may recognize the prairie along the powerline at the State Botanic Garden of Georgia. It is a prime example of the projects that are in the works. It is important to realize that the management of these lands is medicine for them. Land management strategies include planned mowing and prescribed fires. Even though prairies are grassland ecosystems it is important to mow only in the late fall, early winter as to ensure seeds from that season set for the next yearly cycle. Prescribed fires keep back the woody species that encroach into the open land, it is crucial to note that since prairie species have roots several feet into the ground they are not destroyed. Another project within the Athens area is with the ACC Office of Sustainability. A group of roughly 30 volunteers have been working tirelessly throughout the Georgia summer to create a 20,000 square foot prairie along the greenway on MLK Jr Avenue. Most would recognize this area as the walking trail through the Greenway.

Location: Sandy Creek Nature Center along the Oconee Rivers Greenway System.

While it is not feasible for all of us to convert acres of land into prairie space, it is easy for us to get involved in protecting native prairie species and the present pocket prairies in Georgia. Conservationists and scientists are calling on the public to begin to plant native species in home gardens or apartment balconies. These tiny gardens throughout urban or agricultural areas can serve as a refuge for pollinators and wildlife. The State Botanic Garden of Georgia Science and Conservation Team has been building Connect to Protect gardens across Athens and a few others across the state of Georgia. They are great examples of native gardens in small spaces. Along with piloting the Connect to Protect gardens the Science and Conservation team have provided a list of ethical nurseries where you can purchase plants or you can buy directly from the team.

If you do not have the space to plant a garden or hanger planter, the above mentioned groups have also started a citizen scientist project in the iNaturalist website where you can take pictures of prairie plants through the smartphone app while you are out exploring. This project provides information to conservation scientists about where prairie ecosystems are located. This maps locations of species and could be the start of a new pocket prairie. This information is integral to protecting this threatened ecosystem and finding a way to curb climate change. In my talk with Jennifer Ceska about the prairie restoration projects she is helping with she said, “For the first time in my career, we have a hard end date to where we are going to lose these species.†Scientists are predicting that in roughly 20 years it will be too late to reverse the impacts we humans have made on prairie ecosystems. Despite this we are in a unique position to reverse that hard end date and we can do it by asking questions, getting knowledge from educated sources and people, becoming an active citizen scientist, planting native species, and making our own “pocket prairiesâ€.

About the Author

Hi! I am Sammi. I am a Ph.D. Student in the Department of Plant Biology at the University of Georgia working with Dr. C.J. Tsai. I am interested in stress response related to climate change in Poplar trees, specifically involving sulfur transport and orphan genes. I am originally from Nebraska (Go Big Red!) where I grew up and also obtained my B.S. in Biochemistry. I love hiking the north Georgia mountains since moving here and volunteering with shelter cats! In my free time I read, play Switch, attempt to teach myself how to crochet, facetime my sister to see her puppy, and explore Athens

- Samantha Surberhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/samantha-surber/