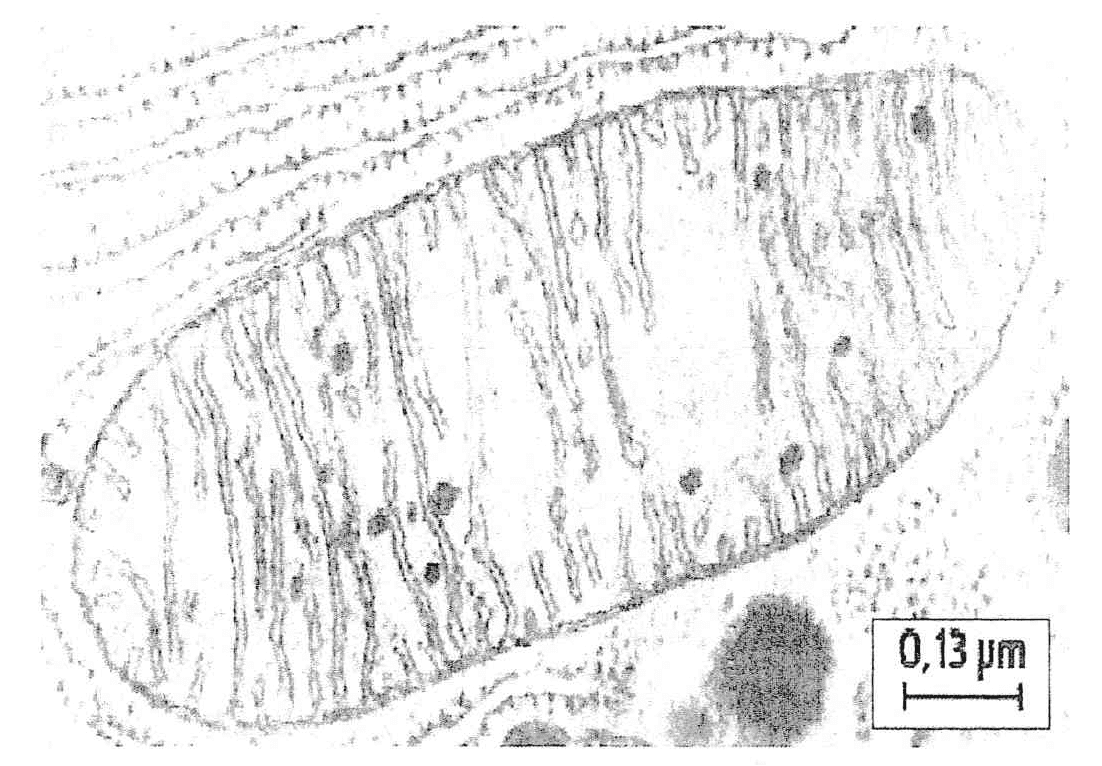

“Therefore, the overall objective of this project is to characterize the changes in mitochondrial metabolism in early VML injury and determine how these contribute to the total decline of muscle contractile and oxidative function.â€

This was the sentence I used to describe the purpose of my dissertation project to my advisory committee. To them, it made complete sense–they are all career scientists with advanced degrees and years of experience in the field of physiology. I could never go around the real world and spout out this sentence as I so confidently typed it out in my project document– the only thing I would get back is a blank stare and the feeling that they now hate me for throwing all those fancy words in their face. So, what exactly do I tell others when they ask about my Ph.D. work? I tell them my project studies severely injured muscle–the type of injury where a portion is lost and is very hard to recover from. I specifically look at the differences in how energy is used in healthy vs injured muscle, how it impacts strength, and what can be done to improve recovery. What's funny is that it took me a whole lot of unlearning bad habits so that I talk casually about my project. But, why, exactly? Well, I was never taught to talk to the community, I was taught to talk to other scientists… and that's a problem.

More exclusive than the 1%

According to a report by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), researchers account for ~0.1% of the global population. This percentage likely does not include graduate students and part-time research employees, but even then, the number of scientists in the world compared to the rest of the population is relatively low. To put it into perspective, if you pick a human at random from the entire global population, it is more likely that person is left-handed, has green colored eyes or blindness, has a disability or mental illness, is double-jointed, or has red hair than it is that they are a scientist. That means that, as scientists, we are catering our research to a very niche audience. Does this mean our research is not relevant to the community at large? No, of course not, but we're not doing a good job of showing it.

Creating communities or cults?

For those of you not familiar, according to Merriam-Webster, jargon is the technical terminology or characteristic idiom of a specific activity or group. Essentially, if you pick a field, there are a group of terms that everyone has agreed to mean a very specific noun/verb. For example (and forgive my terrible Lemony Snicket impression), a chef may say they are sauteing onions, a word which means to fry something in a small amount of fat at a high temperature. It may not be a term that is common knowledge to the global population, but it is common knowledge to chefs. The same thing happens within science; every field has a group of words to help explain observations in a very specific manner.

It's not to say that these terms are bad–they allow us to communicate concisely with others in our field. The problem comes when these words come to the hands of a non-scientist member of the community (or even a scientist that works in a different field). Many of these terms can become confusing because they are unfamiliar and their incidence has only increased in recent decades. Research has shown that when people who are not within a field read documents that contain a lot of jargon, they are more likely to be resistant to the idea that the document was trying to convey, a phenomenon known as motivated resistance to persuasion (MRP). To add to this problem, if an individual then chooses to do further research to try and understand the original document, they find themselves facing increasingly confusing terminology and hitting paywalls. All this makes it more likely for them to turn them away from scientific sources, since clicking a random (and often misleading) article on Facebook is easier than reading a paper. In the age of information, science should not be more inaccessible than it was twenty years ago. This lack of transparency and desire to connect with the rest of the world outside of academic and industrial walls only adds to the problem of mistrust in science.

Bridging the self-inflicted gap

The good news is that, as far as problems go, this isn't the hardest to fix. The very purpose of science communication (sci comm, for short) is to “translate†the science without having it lose its meaning. Of course, there will be a band of resistance against toning down the use of jargon terms in scientific publications. At this point, it's more of a status symbol to make your paper have as many complicated words as possible (and I'm not going to get into the elitism of this practice because we'll be here for another five hundred words). With that in mind, can we come to a compromise? Write your journal article however you want. Enjoy your long-winded sentences and word salad, but make the effort of creating a supplementary bulletin aimed at the community. Engage with the publicity offices at your research institution or talk with local magazines, blogs, and journalists about having a short piece written about your research. The benefit of this will be two-fold: 1) you keep the community informed and are recognized as a trusted expert in your field; 2) once your research is out in the world, you'll be able to control what's being written about it, rather than risk being misquoted by a journalist trying to teach themselves developmental biology.

Let's teach our students and trainees how to talk to the community. There are so many opportunities and organizations (National Association of Science Writers, The Open Notebook, ComSciCon, Science for Georgia, to name a few) whose whole purpose is to guide scientists in their journey to reconnect with the people and to lobby for science in the government. Additionally, events like Three Minute Thesis can help students practice their elevator pitch for a broader audience and resources like the De-Jargonizer helps scientists adapt their writing according to the audience they want to reach. Need instant feedback? Talk to someone you trust who isn't in your field, have them highlight what was difficult to read or understand, and start from there. Like anything, relearning how to talk about your science to the public will take practice, but it's not an impossible task. Broader scientific understanding in our community can only benefit society and boost innovation. Science should be accessible to everyone and its our duty to make that statement true.

Featured image by Marco Verch Professional Photographer via Flickr. Licensed under Creative Commons 2.0.

About the Author

Ph.D. student in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at the University of Georgia, studying strategies for skeletal muscle rehabilitation and regeneration following injury or disease. Interests include mitochondrial physiology, orthopedics, and hugs. Outside of lab, I enjoy reading, listening to true crime podcasts, and griping about the cold like a true Puerto Rico native. You can reach me at jm08293@uga.edu or follow me on Twitter @jey_at_lab.