When you think of farm animals, what comes to your mind? Cows, chickens, pigs, goats, sheep, horses, and so on? Each animal on the farm serves a key role in providing us with food or resources to use. But before we industrialized and invested into the farming industry, these animals were found in the wild. Wild horses still roam the plains in the Midwest and Western United States. But could you imagine the pink and plump pig you see sleeping most of the day away while basking in the mud surviving in the wild? I think not. However, there is a pig that can and does survive in the wild. Let me introduce you to the wild pig.

Maybe you have heard people talk about wild boars, feral swine, feral hogs, or wild pigs. Well, they are all the same species, just with different names. To keep things consistent, we will refer to them as wild pigs. Wild pigs, contrary to the pink domesticated pigs, have long bristled fur that ranges from black to dark brown, may contain unique spotting or stripes along the body, upright ears, straight tails, and large canines, or tusks, protruding from their mouths. Despite their visually distinct differences, there is no difference between domestic pigs in farms and wild pigs, similar to how different dog breeds, like a Siberian Husky and Dobermann Pinscher, look different but are still the same species.

The wild pig, while found in about 35 states, is actually an invasive species. An invasive species, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), is anything living that has been introduced to an area where it would not naturally exist and can potentially cause damage to humans or the economy. As of 2013, this animal is ranked 91 on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN) Global Invasive Species Database due to the destruction and disease transmission wild pigs can cause.

How is the wild pig an invasive species?

Wild pigs were brought over in the early 1500s by Spanish settlers for agricultural and hunting purposes. Escape from enclosures and relocation and release for sport hunting facilitated the establishment of wild populations. To make matters worse, wild pigs can reproduce quickly and efficiently. At the early age of 6 months, they can start reproducing, and have an average of 4 to 6 piglets per litter. These pigs are also able to reproduce year-round and do not have typical breeding seasons, like the white-tailed deer “rut†in the fall., wild pigs have a universal, or generalist diet where they will eat practically anything. While the majority of their diet is composed of plant matter, they are capable of eating just about anything that gets in their destructive path like small mammals, amphibians, and even carrion, or deceased animals.

What type of damage does this animal cause?

The wild pig is notorious for the wide ranging damage it causes: rooting or wallowing damage to plantations, predation on native plants and animals, displacement of native wildlife, destruction of wildlife habitat, and much more. Wild pigs will wallow in muddy locations to cool off during the heat of the day and remove parasites or debris from their fur and will root with its triangular-shaped snout to dig into the soil in search of food. An older estimate of damage from wild pigs to the agricultural and timber harvest industry in the United States puts the annual figure at $1.5 billion dollars but many scholars believe the current damage estimate is much higher – perhaps even double. In 2014, Georgia landowners reported $150 million in damages to agricultural and timber industries and management costs associated with the species.

So, how can we manage an animal like this?

Working to manage or eradicate wild pigs has been an uphill battle. However, in 2014 the US Congress recognized the national threat that wild pigs pose and established the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program under the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services (APHIS). This collaborative program was initially funded at $20 million for employment, supplies, and efforts associated with wild pig removal. APHIS Wildlife Service employees would assist private landowners in location and removal of wild pig populations. In 2018, the USDA Farm Bill added the Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program (FSCP) to the already existing program. The FSCP would be implemented through a collaborative effort between Wildlife Services and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). A total of 20 pilot projects spread throughout 10 southern states have been established, each collaborating with leading universities and scientists to simultaneously conduct research and work toward eliminating the threats that wild pigs pose.

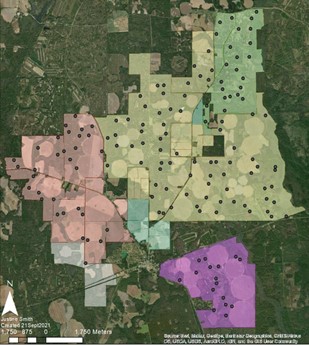

Two pilot projects are ongoing in Georgia, one with a study area primarily in southwest Georgia, and the other in north Florida and extending into southwest Georgia. To collect data, these projects utilize GPS tracking collars and passive trail cameras, which are cameras placed without the use of food or bait to attract animals,. The cameras will provide insight on the pigs' behavior, on influences the wild pigs have on other native wildlife, and will document activity patterns throughout the days and seasons. GPS tracking collars can provide data for establishing home range, or a given area which an animal will regularly use for food or mating, and track movement responses to changes in their surroundings, for example, the increase in human activity during the crop harvesting season. These sampling techniques, paired with removal efforts conducted by Wildlife Service members, will yield important data to help reduce the impact of wild pig damage.

These pilot projects are funded to run until 2023. By then, we will have a multitude of scientific findings expanding on what we know about wild pigs and the long-term effects they have on their surroundings. In the end, we hope to see growth in wildlife populations in response to these removal efforts, and an overall decrease in agricultural and ecological damage associated with the notoriously damaging wild pig.

About the Author

Hello, my name is Justine Smith and I am a Master's student in the Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at UGA. My study focuses on the use of passive camera surveys on private agricultural properties to observe the impact wild pigs have on native plants and animals, and quantify damage to crops associated with the species. I am originally from New Jersey and am slowly but surely acclimating to the intense Georgia heat. When I'm not looking at photos from my cameras, I can be found reading books on the back porch, playing video games, or exploring the woods for some discarded treasures to take home, like deer antlers. Contact me at: justine.smith@uga.edu

- Justine Smithhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/justine-smith/October 23, 2024

- Justine Smithhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/justine-smith/January 17, 2023

- Justine Smithhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/justine-smith/