Whether you drink coffee, tea, or both, it’s hard to deny that we live in a caffeine culture. In 2021 alone, Americans drank over 62 billion servings of tea, and over 60% of Americans drink coffee every day. With such high numbers, tea (and especially coffee) industries are straining to keep people’s daily kick on the table. And the environment is feeling the pressure. As demand continues to rise, so does the clearing of biodiverse natural habitats for plantations. And land eventually runs out.

So, how do we avert this caffeine-fueled doom? One way is to find alternative, more sustainable sources of stimulating beverages to relieve the tremendous pressure coffee and tea industries are feeling. Enter yaupon holly. No, not the spiky stuff you deck the halls with during the holidays. This is a related species, native to the southeastern United States. A relative of South American yerba mate and guayusa, yaupon holly can be brewed into an infusion that not only contains caffeine, but is also packed with healthy antioxidants. As for the flavor, most describe it as similar to black tea, only smoother and with no bitter aftertaste. It’s available from specialty shops online, but yaupon’s infancy as a crop has kept it off store shelves. You might be wondering then, why was it ignored for so long?

For that, we have to go back. Way back.

A Tale of Tea

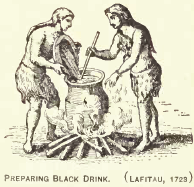

The Indigenous peoples of the southeast were the first to discover the stimulating properties of yaupon tea, and its history as a beverage plant likely reaches back thousands of years. So deep was the plant rooted in Cherokee, Creek, Ai, and several other groups’ cultures that some even referred to it as “The Beloved Tree.” Traditionally, the leaves were roasted over a fire and boiled until the infusion was a dark orange-yellow. The practice caught on with European settlers as well once they arrived, and for a time yaupon was extremely popular in both Indigenous and white communities. Some shipments of dried leaves were even exported to England and France under such names as “Southern Seas Tea” and “Apalachina.”

But just as America’s native tea began to take off, it was quickly stamped out. Seeing yaupon’s rise in popularity as a threat to imported British tea, England limited the importation of yaupon to European countries in the 1780s. Around the same time, the Scottish botanist William Aiton (likely under the influence of the British East India Company) gave yaupon its infamous scientific name: Ilex vomitoria. Reportedly named after the Indigenous purifying rituals of which yaupon was a part, many believe Aiton’s name was part of a politically-motivated smear campaign with the goal of eliminating yaupon as a competitor to British tea. Whatever the motivation, the result was clear. Within a few years, the misleading name, heavy marketing of imported tea, and the forced removal of Indigenous from the regions where yaupon is native had ruthlessly erased the once-esteemed yaupon from American culture.

And so yaupon tea faded into antiquity for almost 200 years…until recently.

Building a Future for Yaupon

In the last 10 years, yaupon has seen a comeback of sorts in the American southeast, particularly in organic and health-oriented communities. Today yaupon tea is mainly produced by a few specialty growers and marketed as a health beverage. While this is a promising start, we’re still a long way from something able to make a dent in America’s massive coffee/tea addiction. Increasing the consistency, affordability, and sustainability of yaupon is going to be central to that goal.

This is where genetics comes in.

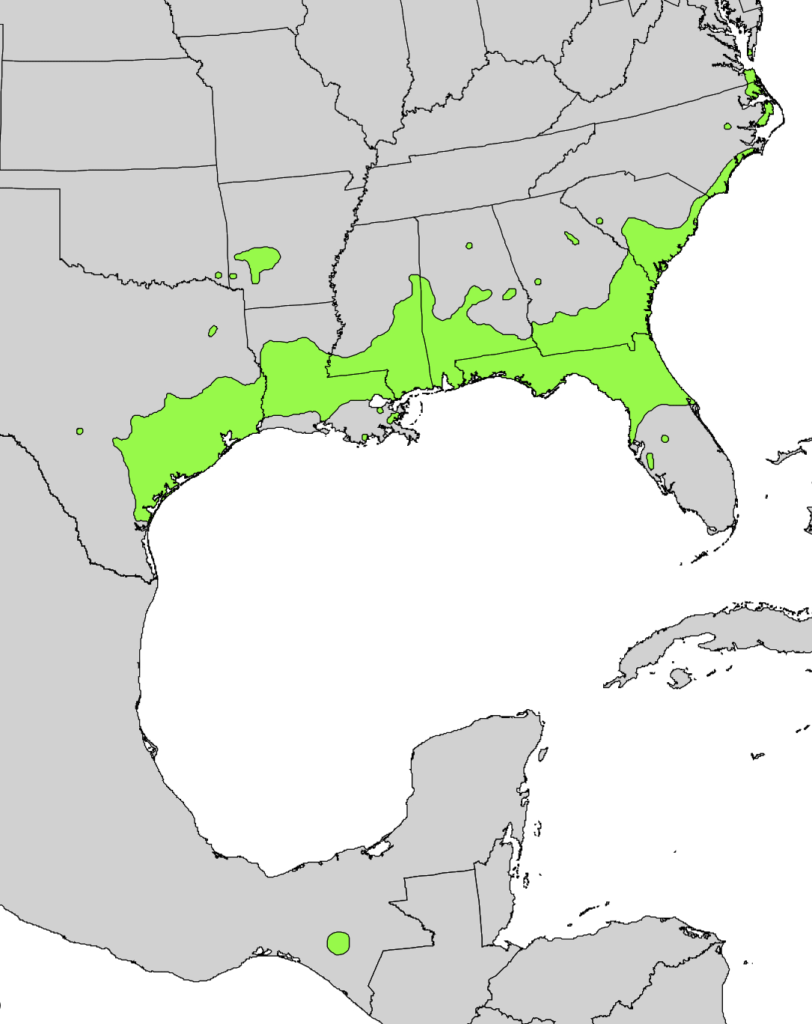

See, many of the varieties of yaupon grown today for tea are wild strains, likely dug up in someone’s backyard and propagated over time into small groves. This would be fine if all yaupon plants were more or less the same, but that’s just not the case. Research shows levels of caffeine and antioxidants vary widely between yaupon plants grown in different places, and part of that variation likely lies in the genetic code. Studying that variation in the wild could help us find yaupon strains that have more commercial potential than the ones being grown now. What we do know is that yaupon has a massive natural range (stretching from Texas to Virginia!), likely to hold a large amount of genetic diversity. Could the perfect yaupon tree be growing out there, waiting for us to find it? Perhaps.

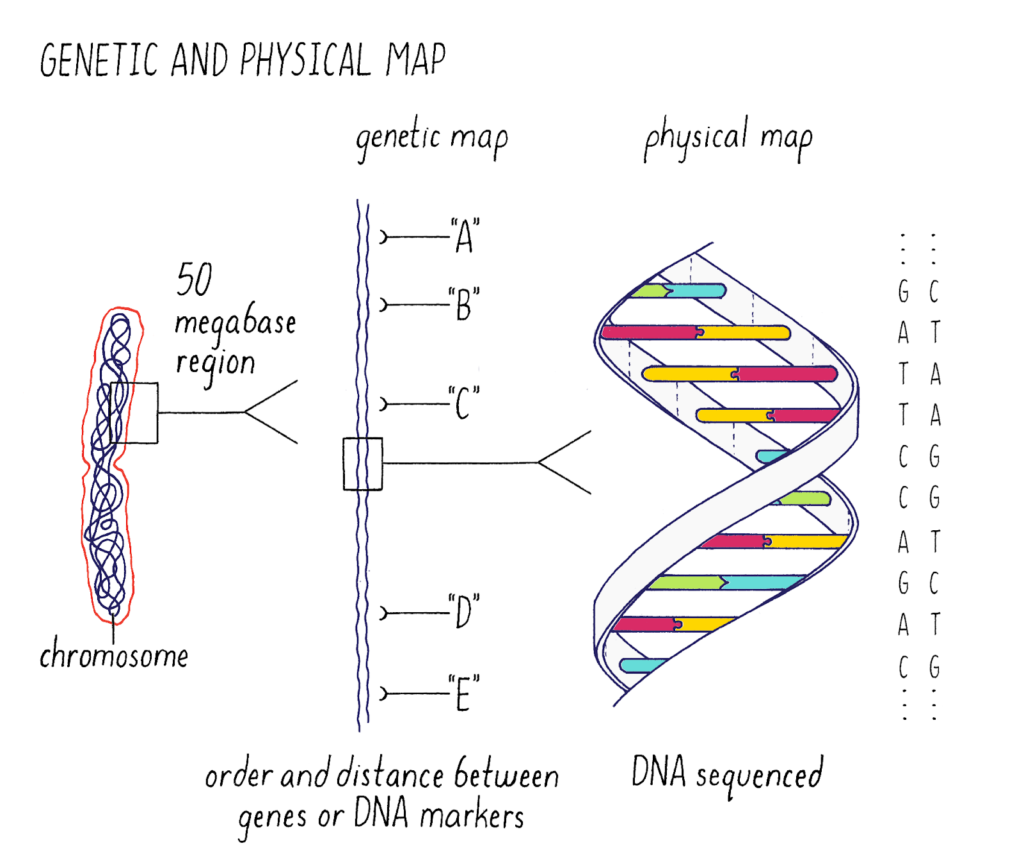

And even if it isn’t, studying yaupon’s genetics could help us improve existing varieties as well. That’s because finding out what genes and environmental conditions are responsible for higher caffeine, better plant hardiness, and so on is like building a roadmap to the millions of As, Gs, Cs, and Ts that are the building blocks of a genome. These building blocks form genes, which are like specific sections of road that we can identify again and again, even in different plants. Once we know each gene’s effect on something we care about (like caffeine), we can use them to “navigate” what at first glance looked like a bunch of letters. This ability to find our way through the genome allows us to more easily predict what traits a plant will have, given what variation in its genes (or “alleles”) it has. Breeders can then use this info to naturally breed plants that have more of the good stuff, which is how we get varieties that are able to be grown at large scale.

But finding the perfect yaupon is not enough. We also want to be sustainable. After all, what’s the point of replacing one forest-clearing crop with another? Yaupon holly is an important part of maritime forest and dune habitats on the southeastern coast, which means wild harvesting would be bad news for these ecosystems. Wild populations of crops are also gold mines of information for breeders and researchers, and losing them can prove disastrous. For example, the most widely-grown variety of coffee is at high risk of being wiped out by disease and pests because most of its wild relatives have been driven practically to extinction. So let’s learn from our mistakes. Any yaupon specimen with desirable traits should be preserved in its natural habitat and propagated via cuttings. It will also be important moving forward to catalog and protect yaupon’s diversity in the wild. Genetics can help here too. Once we know how the DNA sequences of yaupon populations vary over space, land managers can then use that data to inform which areas in parks and preserves are the most diverse and need protecting the most.

Finally, it is important to remember effective land management and the brewing of yaupon tea itself are both practices perfected by the American Indigenous long ago. Unfortunately, many of the tribes that historically used yaupon were relocated in the late 1800s to areas where yaupon does not grow natively. As yaupon tea continues to rise in popularity, it is crucial we keep American commercialism from destroying this already endangered part of Indigenous culture. Simple acknowledgement is not enough. The opportunity (but not coercion) for tribes to collaborate in scientific research on yaupon with full authorship status and access to data is the bare minimum expected from ethnobotanists and geneticists. Ensuring Indigenous growers and breeding programs have full access to wild-collected plants and genetic data on important traits is also expected. This is only the baseline, however; researchers and growers alike will need to communicate directly with tribes to make each party’s needs and expectations heard. The goal: a truly equivalent exchange of knowledge and culture.

We’re still a ways off from sustainable yaupon tea being served at every local cafe, but the time it takes to do it right will be worth it. The story of yaupon tea is bathed in greed and ignorance – one look at its scientific name is enough to understand that. What matters now is how we process the past and move forward. Learning more about this incredible plant using the power of genetics, protecting its important niche in the wild, and ensuring the Indigenous that first discovered yaupon tea’s properties benefit from these advances, well… that’s my cup of tea.

About the Author

Ben Long

Ben Long is a Ph.D student in the Department of Genetics at the University of Georgia studying both the population genetics of yaupon holly, a naturally caffeine-containing plant native to the American southeast, as well as the microbiomes of plant hosts and their pathogens. Outside of the lab, he enjoys playing his ukulele, foraging wild medicinal plants and homebrewing various beverages.

- Ben Long#molongui-disabled-link

- Ben Long#molongui-disabled-link