If you want to travel somewhere to reconnect with nature and learn about ancient history, go to Mexico City. South of this metropolitan city is 22,000 acres of “floating gardens” interconnected by an intricate water canal system. These floating gardens, known as chinampas, are an ancient Mesoamerican agricultural practice that is still used today. At the height of the Aztec empire, the chinampas were so productive that they were used to feed over 200,000 inhabitants in the capital of Tenochtitlan. The ancient practice ended with the arrival of Spanish colonists, but thankfully, historical records and oral traditions shared across generations of farmers for half a millennium have allowed chinampas to make a return. The floating gardens in Mexico City are important to the cultural identity of the region, helping connect the urban community to nature and reconnecting individuals with their ancestral roots. Chinampas are also important for ecological diversity and can provide sustainable solutions to modern day agricultural and urbanization problems.

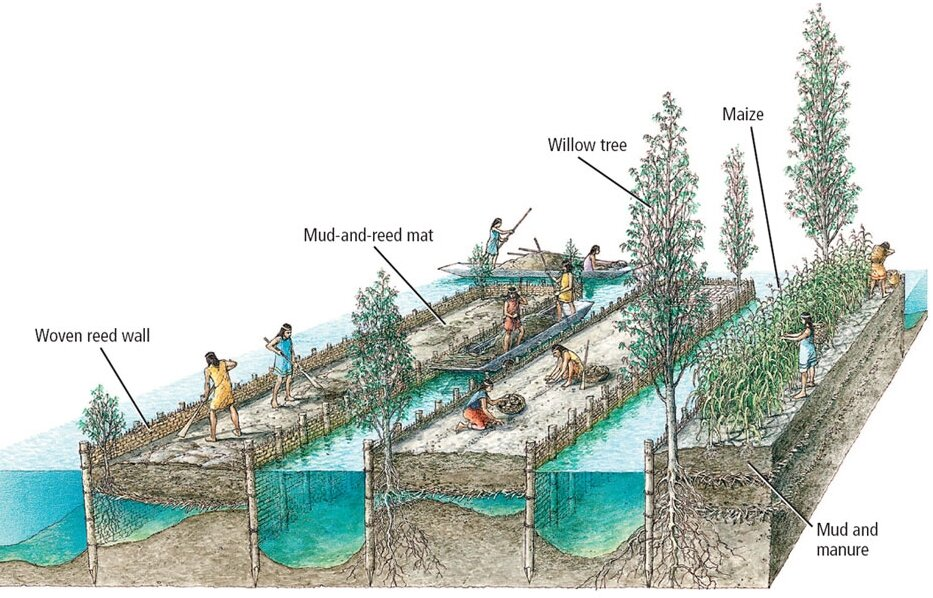

Today, Mexico City is facing a serious drought as there is limited water supply in the city’s aquifers. The problem faced by Mexico City’s inhabitants’ today is a stark contrast to what individuals faced half a millennium ago. Before the establishment of modern day Mexico City, the area was once composed of five large lakes surrounded by wetlands. The ecology of the environment forced early Mesoamericans in the area to develop farming techniques to maximize the limited available land they had. To do this, they developed the chinampas which comes from the Nahuatl word chinamitl meaning “hedge close to the reed”. These chinampas are built by creating small, artificial islands in the middle of a lake or wetland. First, farmers need to dig up mud, solid, and decayed vegetative matter, and pile it into a plot about 100 ft x 10 ft. (though the chinampas that surrounded Tenochtitlan were recorded to be about 3 x times that size!). The artificial island is held together with reed fencing, usually from willow trees, below the surface of the lake to help prevent the island’s erosion. The fencing is also important for the formation of the canals; farmers typically ride boats up and down these canals to work on the chinampas. Willow trees were also planted at the corners of each plot to help provide shade and anchorage.

Archeological evidence incorporating aerial photos and remote sensing suggests that early Mesoamerican groups like the kingdom of Xaltocan used the chinampas system as early as 1250 BC. Prior to the Aztecs, chinampas were typically small scale individual owned farms. It wasn’t until the rise and growth of the Aztec Empire did the adoption of large scale chinampas farming begin. At the height of the empire around 1500, the chinampas system in the capital of Tenochtitlan was able to feed over 220,000 inhabitants. To be able to produce such large quantities of food, the Aztecs built several irrigation networks and flood systems to support the vast network of floating gardens that surrounded the capitol. In 1521, Spanish colonists overthrew the Aztec Empire and the lakes of the Valley of Mexico were almost entirely drained. The Spanish built their capital “New Spain” atop the ruins of Tenochtitlan and the large-scale use of floating gardens in the area was erased. However, smaller farmers in the surrounding area continued the practice and their knowledge of the system has been pivotal in the revival and reconstruction of chinampas in modern day Mexico City.

In 1975, the Mexican government began a major project to help rebuild chinampas in several states, relying on small traditional farmers in Lake Xochimilco near southern Mexico City. These small farmers used oral traditions passed down from generations to help them rebuild the ancient garden beds. Today, the chinampas systems have incorporated many novel approaches to help mitigate the negative effects of drought and pollution from heavy urbanization and tourism. Most modern-day chinampas include biofilters to help keep trash and other debris out of the canal ways, and much of the gardens would be used to feed cattle rather than grow crops. Some floating gardens are built with ditches that help bring extra water from the canals and for more drainage.

Another recent revival occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic when many people began to realize the necessity of fresh foods and connecting with nature. Lake Xochilmilco is a popular spot for tourists to ride trajineras (boats) up and down the canals to admire the chinampas. Along the canals, vendors will sell snacks and knick knacks, mariachis will play live music, and riders can even enjoy a delicious meal on the boat ride. Although this popular activity has bolstered the growth of the chinampas, locals have had to adapt their farming techniques from production to presentation. In interviews with farmers, many have said that they have shifted their production and practices to fit more in line with the needs of the expanding agritourism business. Many chinampas now grow ornamental flowers rather than the traditional crops of corn, beans, and squash. Although agrotourism has caused changes in the priorities of chinampas farming, the business continues to bring in revenue for the construction of more chinampas which will promote ecological diversity in the area and help connect people to nature.

The chinampas in Lake Xochimilco hold nearly 2% of the world’s biodiversity and 11% of Mexico’s overall diversity. These floating gardens are home to a variety of birds, fish, crustaceans, and the endangered axolotl, a highly regenerative salamander that was near extinction due to urbanization and water pollution. Scientists from the National Autonomous University of Mexico have recently begun a project working with local farmers to help reduce pesticide usage and increase the population of this threatened species. The continual expansion of the chinampas will hopefully improve the populations of these endangered creatures and provide homes for many other animals.

This highly productive and sustainable ancient farming practice could also help solve some of the problems facing modern-day agricultural practices. Today we face the issue of land scarcity, and many fields require large amounts of fertilizers to help plants grow in soils whose nutrients have been depleted due to over-farming. Chinampas maximize space and can be built on top of urban waterways which may otherwise not be considered farmable land. They also do not rely on an artificial water system that would require energy to power, making the cost of watering extremely cheap. However, irrigation systems like those used during the Aztec Empire, would greatly improve overall production during dry seasons. Chinampas are a highly productive system because the sediment from the lake’s bed seeps into the mud of the canals which can be taken up by the plants, and the nutrient-packed mud itself is used to replenish the topsoil. Ancient farmers recorded being able to harvest up to seven times a year, a significantly higher number of times than most modern-day farming practices. Incorporating chinampas farming into our agricultural systems could improve land use, soil health, and has the ability to be highly productive to meet our food needs. Beyond solving problems to modern agricultural problems, we should learn about how the chinampas are able to bring communities closer to nature.

Many cities around the world have taken the concept of the floating garden and built them in primarily urbanized areas, maximizing space and serving as green spaces for people to enjoy. For example, in Chicago, the Urban Rivers program has built floating parks to help transform 17 acres of urban waterways into beautiful and diverse landscapes for people to appreciate nature. This project draws inspiration from the creation of artificial islands in a waterway just like the chinampas. The space allows the inhabitants of Chicago to connect with nature by walking on top of the floating garden or by kayaking in the canals. In Osaka Bay, Japan, Shimizu corporation is trying to build an island on top of the ocean where plants will grow inside a 1000 m tall skyscraper unaffected by environmental problems like typhoons and rising sea levels. This project may have been inspired by the sustainability of the chinampas, with the desire to create an oasis that maximizes the amount of available space. While the Green Float project has not been completed yet, the overall goals like sustainability and connecting people with nature seem to be a common theme inspired by the ancient Mesoamerican chinampas.

Aside from agricultural benefits, the chinampas are also important for the community as they are integral to the cultural identities of many people. In 1987, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations recognized the cultural significance of chinampas and deemed them an agricultural heritage system. For many people, the chinampas represent resilience, innovation, and the importance of maintaining traditions. The closed system of the chinampas can teach us how to deal with the exploitation of land and nutrients, a common problem we face today. Beyond chinampas, we should continue to learn from other ancient agricultural systems.

If you yourself are interested in building your own floating garden at home, please read the University of Florida’s extension article: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/HS184?downloadOpen=true.

About the Author

Dionne Martin is a Ph.D. student in the Genetics Department at the University of Georgia. Their research focuses on identifying key genes involved in potato tuber development and uncovering the evolutionary origins of tuber development across plant species. Outside of the lab, they enjoy watching UGA football, hanging out with her two cats, and doing Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

-

Dionne Martinhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/dionne-martin/December 4, 2024