Floriography, better known as the language of flowers, doesn't refer to a communication method between plants. Rather, it is the Victorian era practice of gifting arranged flowers to communicate a coded message: a red rose for love, a white tulip for forgiveness–things you may want to be familiar with this upcoming Valentine's Day.

Long before this idyllic period of floriography stood an especially symbolic flower: the blue rose.

Blue roses have appeared in multiple cultures to signify something impossible, a non-existent object. Despite the many stunning colors a rose may produce, from a deep red to creamy beige, a blue-colored rose does not occur in nature. The Rosaceae family of plants, to which roses belong, is incapable of making anthocyanin, the pigment responsible for imparting a blue color to other plants such as violets. Much to the chagrin of horticulturists for centuries, without a gene capable of producing the pigment, no amount of selective breeding could ever give rise to a blue rose. However, with a better understanding of the molecular biology of roses, coupled to the application of genetic engineering techniques, this particular “blue rose†of a task may soon be achievable.

In the past couple decades, there have been two significant biotechnological breakthroughs related to the creation of the blue rose. The first and most successful story is from Suntory, a Japanese distribution company, dipping their toes into the realm of biotechnology. The initial task was to isolate several genes responsible for the specific blue anthocyanin. After years of effort, these genes were successfully introduced into the rose, but two issues had to be addressed.

First of all, legal and ethical hurdles of working with and marketing a genetically modified organism, or GMO, needed to be addressed. This is a subject most people know about, but usually in the context of things that are made for consumption. Given the biggest arguments against a GMO tend to be from a food safety perspective, would something made purely for aesthetic appreciation be made to go through the same hurdles? The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety is an international agreement to mandate the handling and use of any GMO regardless of their purpose. In the case of blue roses, this meant ensuring there were no ill-effects to insect populations, and preventing dispersal of the transplanted genes through cross-pollination with other plants.

The second issue scientists faced was the longevity of the pigment itself. Even though the roses were capable of making anthocyanins, they were not necessarily maintaining a blue color. Due to where the pigment was accumulating in the cell, the corresponding pH could change the blue shade into more of a pink. A similar phenomenon has been observed in Hydrangeas, based on the pH and metal ions available in the soil!

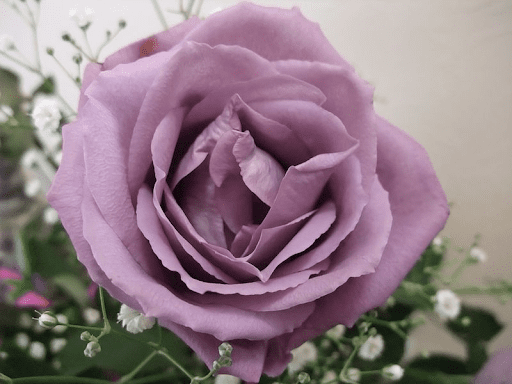

After experimenting with several gene expression combinations in over 40 rose varieties, a stable transgenic line known as the Applause Blue Rose by Suntry was born. This variety is heralded as the first “blue roseâ€, but due to the formation and placement of pigments, it appears mauve rather than the striking azure of the daytime sky. While not the exact color desired, it is still unique to any other naturally formed rose, and wildly popular.

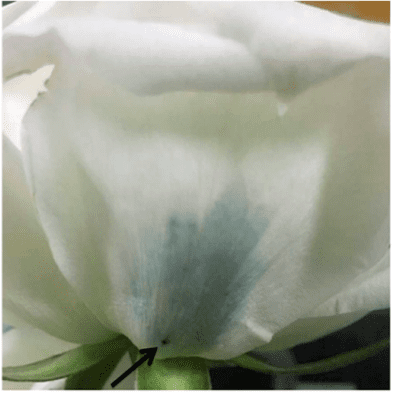

The second biotechnological advance towards blue roses is a cursory proof-of-concept paper published August 2019 in ACS Synthetic Biology. In this work, instead of using genetic engineering to alter pigment pathways, they looked into bacterial enzymes. A construct was made in Agrobacterium, a bacterium capable of infiltrating plants. This bacterium expresses an enzyme which converts L-glutamine, an amino acid used by both plants and animals to build proteins, into the blue pigment indigoidine. Initial trials of this proved to work, and the introduction of the bacterium into the flower bud resulted in an inkling of blue petals.

While these results aren't the striking full-flower color seen in the Applause variety, it provides a much more blue hue and builds the framework for what scientists are hoping to be a breakthrough in floral agriculture. As such, the blue rose may mean “impossible†in the language of flowers, but to quote Vanna Bonta, “‘Impossible' is not a scientific term.â€

About the Author

Jeremy Duke is a Biochemistry and Molecular Biology PhD student at UGA, focusing on glycoconjugate vaccine development. He has a wonderfully eclectic music taste and likes to make costumes and read when there isn't a pipette in hand. He can be contacted at jad71457@uga.edu.

-

This author does not have any more posts.