Here is my confession: I have a weakness for raw oysters. Cooked they're tasty, but raw they're sublime. There's just something about that briny, gooey goodness (with just a hint of lemon juice and cocktail sauce, thankyouverymuch) that I can't get enough of. You may have heard the old adage that says never to eat raw oysters during a month with an “R†in its name. Like most old adages, this is not always true, but it's based on some pretty good advice.

Now that summer is officially here, we've got hot weather, longer days, and — you'll notice — we're right in the middle of several months conspicuously absent of the letter “Râ€. This is not coincidence; those R-less months coincide with some of the hottest weather of the year. If you're the sort inclined to escape the heat at the beach, Athens is in close proximity to both the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic. Georgia's barrier islands are home to some pretty cool wildlife, but this time of year the offshore flora and fauna are teeming, too, and our regional saltwater is home to one nasty little bacteria that finds summer heat particularly appealing.

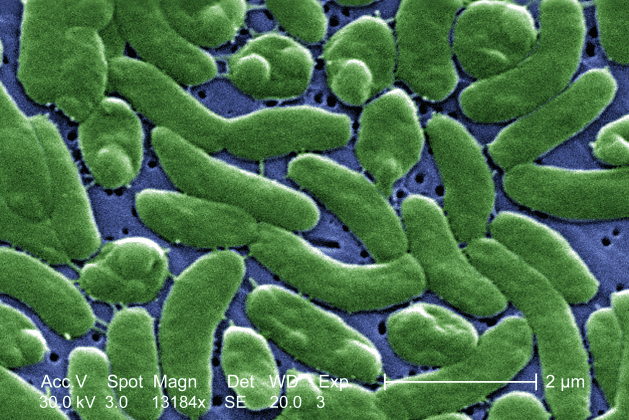

The traditional concern with consuming raw summer oysters is none-other than our regional, heat-loving bacterium: Vibrio vulnificus, a cousin of the cholera-causing Vibrio cholera. Unlike its more notorious cousin, V. vulnificus is not spread from person to person, and it probably won't kill you. This bacteria poses a severe, and sometimes fatal, risk to individuals who are already chronically ill — their immune systems are already overloaded — but to a typical, healthy adult, the risk is much less dire: you're only looking at a few uncomfortable days with lots of visits to the porcelain throne. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates nearly 50,000 cases of food-poisoning-like illness derived from V. vulnificus annually, but luckily, less than 1% of those cases are severe.

Keep an eye out though, eating raw oysters is not the only way to catch this bacteria: it also has a nasty penchant for entering open cuts and scrapes in the skin, which can produce a severe, and sometimes fatal, flesh-eating response. Saltwater may have a reputation for being good for cuts, but it is also home to a wealth of nasty little bugs. If you have a cut that hasn't healed, try to avoid the ocean, or if that's not possible, cover it with a waterproof bandage.

V. vulnificus occurs naturally in salt water, and in brackish areas on the coast where freshwater meets the ocean. It's found year-round, but during the summer (those R-less months) when the weather warms up, these bacteria really thrive. Oysters are filter feeders and eat by sucking in salt water, consuming free-swimming phytoplankton, and the occasional V. vulnificus, from their surrounding water before spitting the water back out into the ocean. The good news is the bacteria is easily killed by cooking, so only raw or undercooked oysters pose a risk. Additionally, post-harvesting methods, such as rapidly cooling and refrigerating oysters, or steaming them at low heat, have been developed to further reduce risk of V. vulnificus, but the effectiveness of these methods seems to vary.

While this all might sound a little alarming, you certainly don't have to completely avoid fresh, raw oysters during the summer (I know I don't!) However, you should be aware that you're at increased risk of getting sick from V. vulnificus during this time, particularly with oysters sourced from the Gulf of Mexico.

But what about all those months with Rs, you ask?! Proceed to indulge! But use caution. The unfortunate truth is that there's always a slight risk in eating raw oysters, so no time of year is totally foolproof. You might well be safer going for that slimy mollusk in March, but it's not guaranteed to not make you sick. This is because eating raw seafood always contains some inherent risk, and like all shellfish, oysters that aren't fresh, stored properly, or served correctly are at risk for spoilage. Be vigilant for oysters that look or smell “off‖a sure sign of spoilage.

But be aware that where V. vulnificus is concerned, even an oyster that has been expertly prepared might still make you sick if eaten raw, even if it looks, smells, and tastes just fine. A V. vulnificus-infected oyster is indistinguishable from the perfectly clean one sitting next to it. Oysters are sneaky.

So my advice to you is this: go forth and eat oysters year round! But make sure they're sourced from a reputable (and preferably chilly) location. And if your immune system isn't so hot? Definitely opt for the cooked oysters, just in case.

Featured Image Credit: Acme Oysters by Tyler via Flikr

Caitlin Mertzlufft is an Athens native, and a PhD candidate in the Integrative Conservation &Geography program at UGA. Caitlin’s research combines geospatial analysis and public health, and she is currently using satellite imagery to estimate Chagas disease transmission in central Panama. When she’s not looking at palm trees from space, she enjoys running, nerdy board games, and all things coffee. Follow her on twitter @CaitlinMertz or send her an email at cmertz2@uga.edu. More from Caitlin Mertzlufft.