On my walk home from work, I almost always encounter what I affectionately call “trash creaturesâ€: squirrels that pop out of dumpsters carrying slices of pizza or crows pulling apart garbage bags to get at the tasty morsels inside. While undoubtedly amusing, these incidents may have more cryptic, and sinister, consequences to the health of wildlife populations. Because when humans move resources around, the animals, and their parasites, come along with them.

In 1994 in Australia, a Thoroughbred racing mare named Drama Series started showing strange symptoms including fever, restlessness and neurological signs such as an uncoordinated gait and muscle twitching. Veterinarians, trainers and stable hands worked to save the mare from this mysterious illness, but within 48 hours the valuable animal had died without a diagnosis. Within a week, the 19 other horses Drama Series was stabled with became ill with similar symptoms: 13 of which died soon after and the remaining six animals were euthanized in an effort to control the outbreak. The disease was not just limited to horses however; their trainer and a stable worker both fell ill with flu-like symptoms within one week of Drama Series' death. The stable worker recovered but the trainer tragically died of the disease.

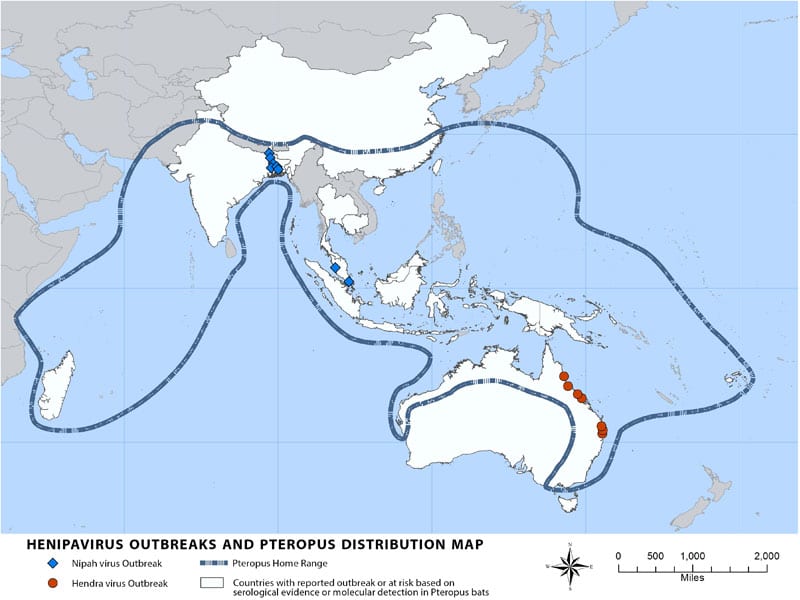

The cause of the outbreak was later discovered to be an emerging virus, now called Hendra virus (after the town of Hendra, Australia where Drama Series lived). This virus normally passes between flying foxes (Pteropus sp.) without causing the animals any harm. However, when the virus jumps hosts to humans or horses, it causes a very high mortality rate (60% in humans and 75% in horses). It is thought that people encroaching into native flying fox territory have pushed these animals out of their homes and into neighborhoods where they forage on ornamental fruit trees. Flying foxes are exceptionally messy eaters, sloppily eating fruit from the trees and then discarding their saliva-covered leftovers on the ground. Horses will happily eat these sweet treats and unwittingly contract the virus. By changing the landscape in Australia, people forced the native wildlife to interact more closely to humans. This led to a previously undiscovered infectious disease spreading and killing beloved animals and their human caretakers.

An example closer to home is the emergence of Mycoplasmal conjunctivitis in house finches across the north east. It was first discovered in Maryland in 1994 when residents noticed birds at their feeders with extremely swollen and red eyes; so much so that the eyes bulged out of their heads and the crust that formed completely sealed the bird's eyes shut. The disease moved rapidly across the entire United States, reaching the center of the country three years later and then California nine years after that. The Cornell Lab launched an enormous citizen science project to research the spread of the disease, and discovered that it was caused by bacteria transferred at bird feeders when infected birds would scrape their eyes reaching in for seed. By providing a constant source of food, humans increased the density of house finches and concentrated them in a small area. This clustering initiated and perpetuated the outbreak of a devastating bacteria that caused significant mortality in the birds.

These two examples highlight how human activity can have unforeseen consequences on animal health. Ecosystems, animal populations and disease dynamics are incredibly complex systems that interact with each other in sometimes unpredictable ways. Luckily, scientists have recently recognized this and there is a robust group of researchers at the University of Georgia who are investigating these relationships. Their work falls under the umbrella of “One Healthâ€: where healthy environments lead to healthy animals which lead to healthy people. You can read more about One Health in a previous Athens Science Observer post. We can all take part in keeping animal populations healthy by following recommendations from researchers about wild animal food supplementation and waste disposal – to ensure disease-free animal populations continue into the future. Locally, you can contribute to this effort through the citizen science project monitoring house finches which is still ongoing; if you are interested in contributing please visit their website.

About the Author

Megan Tomamichel is a PhD student in the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia. She studies aquatic disease ecology and is working to understand the causes of deadly disease outbreaks that threaten the world's fisheries. Her favorite past times are aquarium building, hiking, drinking too much coffee and dreaming up names for future pets. You can reach her at Megan.Tomamichel@uga.edu

- Megan Tomamichelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/megan-tomamichel/November 30, 2021

- Megan Tomamichelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/megan-tomamichel/October 29, 2020

- Megan Tomamichelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/megan-tomamichel/March 26, 2020

- Megan Tomamichelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/megan-tomamichel/November 18, 2019