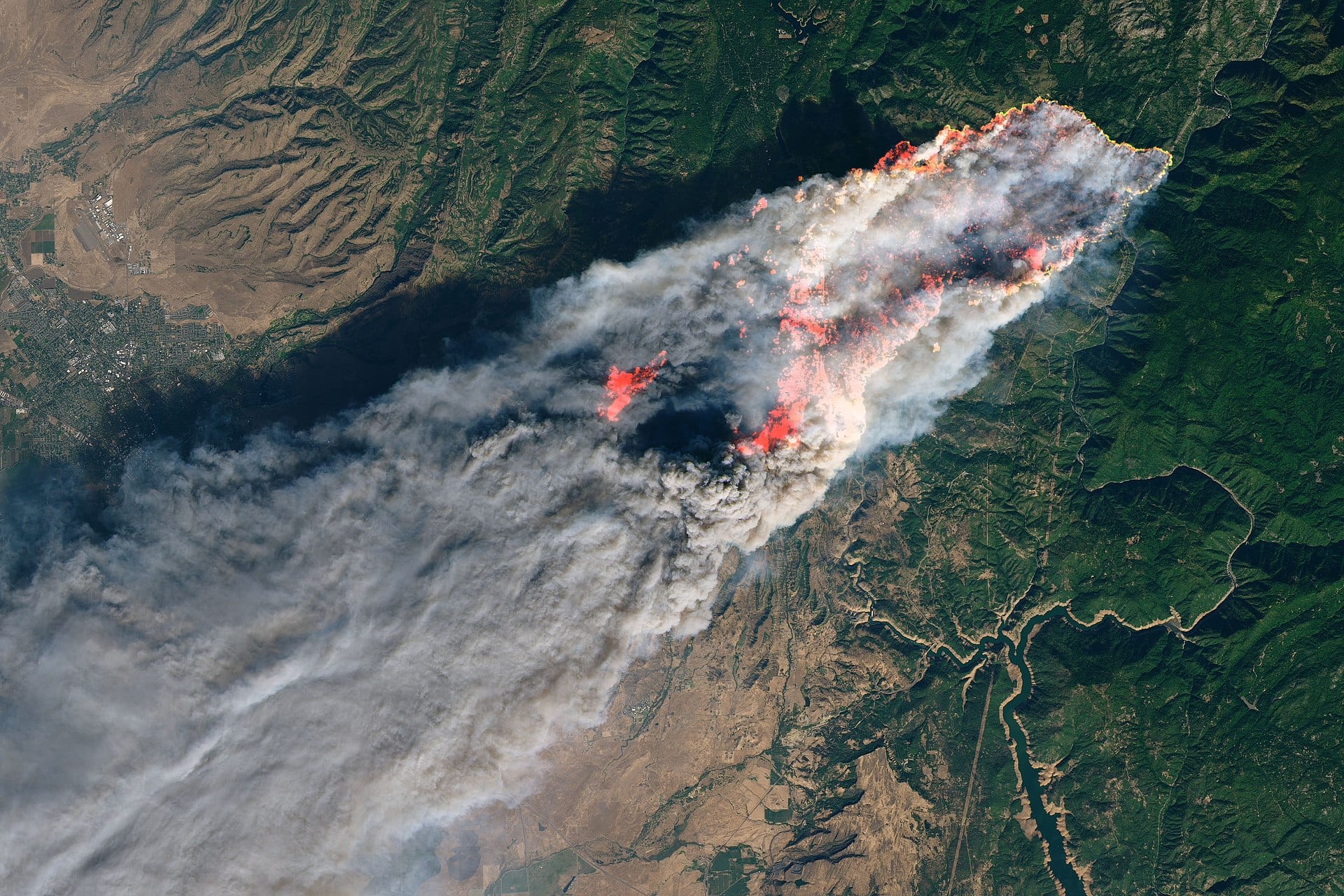

In recent years, it feels like we have watched parts of the world be swallowed whole by fire, painting a very apocalyptic picture of the future. Nearly 40,000 square miles in Australia were decimated by bushfires last year. California's Camp Fire displaced about 50,000 residents, and Indonesia saw over 2 million acres of land consumed by flames, including precious orangutan habitats. The scale and frequency of this destruction feels unprecedented, but what's causing them? And why now?

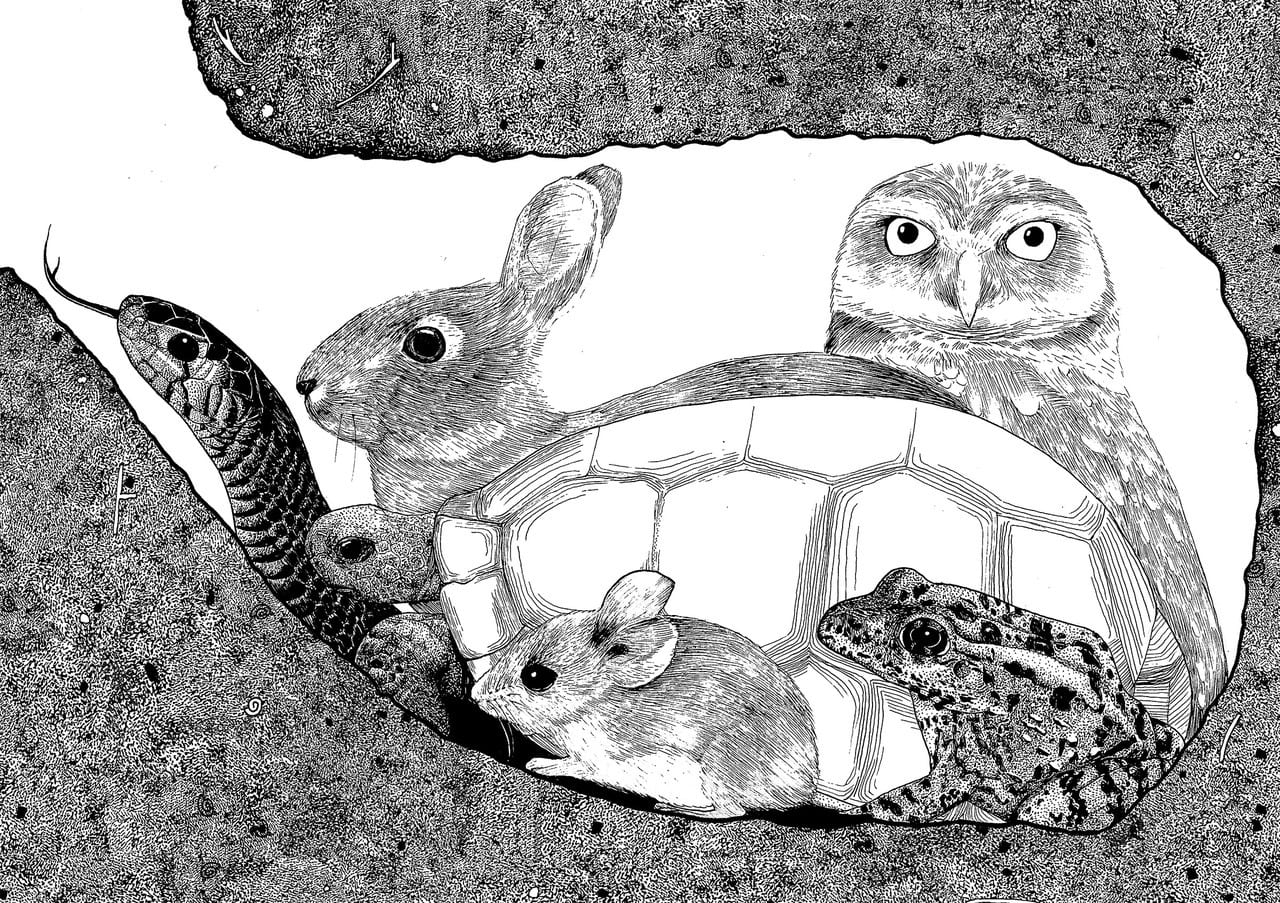

In the Devonian period around 400 million years ago, a rise in trees caused a rich production of oxygen in the atmosphere; with that came the natural process of forest fires instigated by lightning. The fiery landscape continued for millions of years, whilst organisms evolved alongside it – the results of that coevolution are easily seen today. For example, Jack pine, a pine tree native to the northern US and Canada, evolved serotinous pine cones, which only open to spread seed in intense heat. The longleaf pine, Jack pine's southern relative, developed different growth stages that revolve around fire, with its seedlings being essentially fire-proof. Smaller understory plants evolved to store more of their carbon-rich biomass underground, effectively ‘hiding' more of themselves until the fire passed. Plants weren't the only ones to innovate – animals, too, have evolved to thrive in a fiery ecosystem. Take the gopher tortoise, for example, which is considered an ‘ecosystem engineer'. The tortoise's burrows become the perfect underground bunker for it, and hundreds of other species, to wait out a fire.

Historically, fire has been a valuable tool for humans and their ancestors, who have been using it as early as one million years ago in Africa. With their arrival in North America around 14,000 years ago, early humans learned to use controlled fires – what we now call prescribed burns – to their benefit. The purpose of these burns was multifaceted. They provided mineral ash and carbonized leaf litter, which settled and fertilized the soil, creating a rich substrate for agriculture. The fires also facilitated hunting. The tender new growth of shrubs and grasses attracted animals, which hunters could more quietly stalk in the newly cleared forest.

These adaptations by plants, animals, and people played a role in the establishment of fire-dependent ecosystems. In North America alone, these range from savannah plains and swamps, to conifer forests. However, with the arrival of colonialism on the continent in the 15th century, forest fires were deemed destructive and wasteful. Ironically, the land the colonists saw as pristine and untouched by man was the result of millennia of fire practices by natives. The combination of fire suppression and excessive logging by the colonizers left ecosystems massively disturbed. Flammable forest debris build-up, what foresters call “fuel,†was left unchecked, leading to devastating wildfires. These wildfires, unlike prescribed fires, are uncontrollable, extremely hot, and damaging to plants and animals. As early as 1910, a series of wildfires known as the Big Blowup, swept through three states and killed 85 Americans. These are the same fires we see today, torching millions of acres on the news.

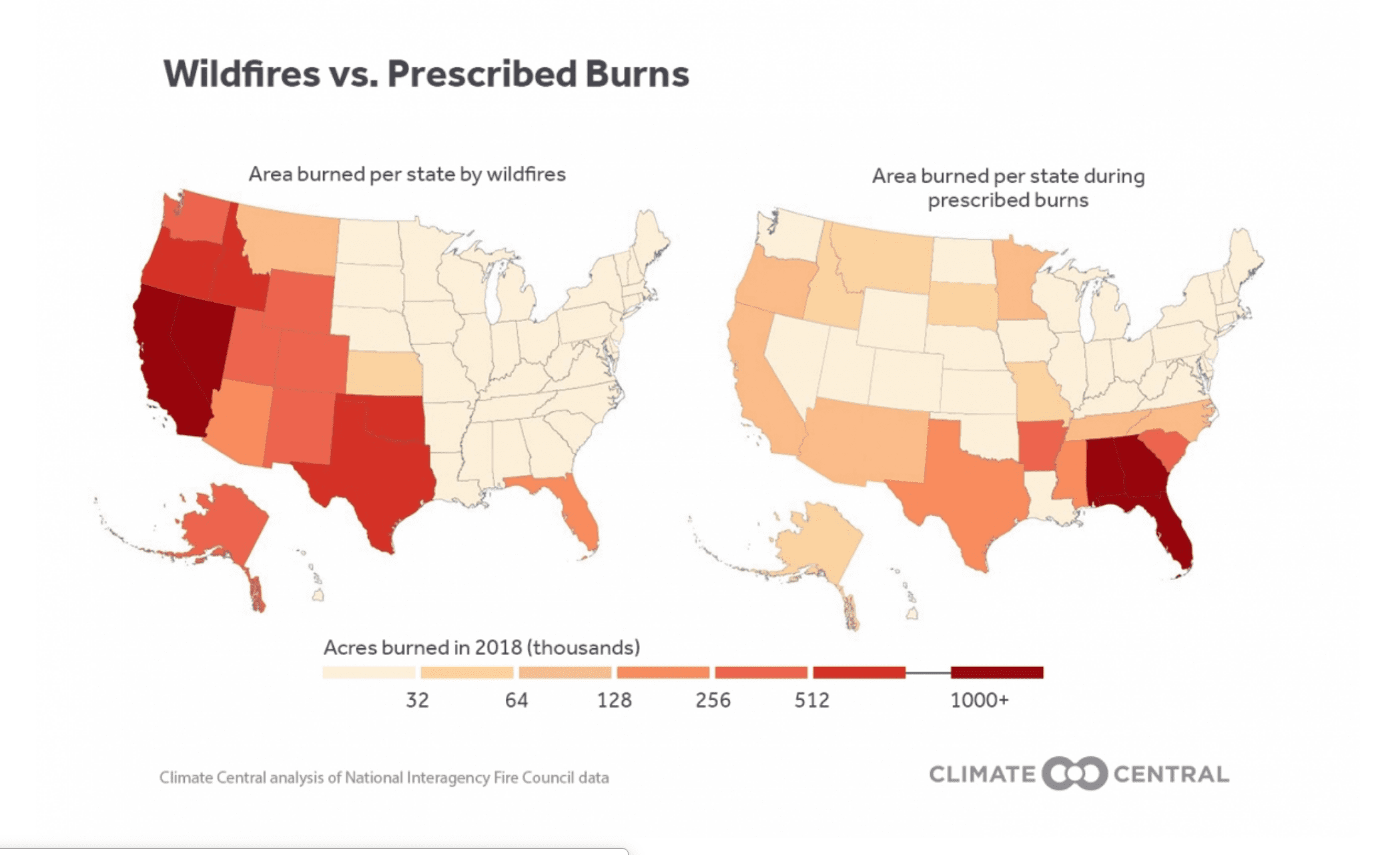

Now that we better understand forest and fire ecology, forest managers can facilitate natural processes by incorporating prescribed burns in management practices. But prescribed burning is not implemented in every fire-dependent ecosystem in the US. In the southeast, prescribed burns are heavily implemented; whereas in the west, prescribed fires are not as incorporated into management practices.

Of course, prescribed fires near residential areas or highways can present urgent safety concerns, especially for those with respiratory illnesses. Non-fire solutions to prevent the accumulation of fuel have been explored, such as allowing goats to intermittently graze potentially flammable grasses. The Forest Service also puts an emphasis on outreach and education, providing people with the tools and knowledge to prevent wildfire on both public and private lands.

There is no singular answer as to why wildfires like the ones we see in Australia and California are so destructive – but it can be boiled down to fire suppression and the dark cloud looming over everyone's environmentally conscious head, climate change. There is no doubt that the frequency and severity of wildfires will increase as extreme droughts and higher temperatures are expected in the wake of climate change. Mitigation of climate change is imperative to reducing these wildfires, and so is education. The US Forest Service is taking measures to educate the public on the benefits of prescribed fires and how we can prevent wildfires, since more than 80% of wildfires are caused by people.

Our dependence on forests is more than one can imagine – in unexpected ways too – and preserving these ecosystems is integral to saving ourselves, the land's history, and the millions of beings who were here before us. Find out more on how to prevent wildfires and how to curb climate change.

About the Author

Simone Lim-Hing is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources studying the host response of loblolly pine against pathogenic fungi. Her main interests are chemical ecology, ecophysiology, and evolution. Outside of the lab and the greenhouse, Simone enjoys going to local shows around Athens, playing Mario Kart, and reading at home with her cat, Jennie. You can reach Simone at simone.zlim@uga.edu or on twitter @simonelimhing. More from Simone Lim-Hing.

- Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/March 11, 2024

- Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/March 18, 2021

- Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/

- Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/