We are heavily entwined with forests. The structure of your house is likely southern pine. The package you ordered in the mail is encased in wood pulp. The stuff that makes your toothpaste thick is cellulose from wood. We rely on trees as a renewable resource for our daily activities and well-being. However, our own actions are now threatening this very resource – human-driven climate change is radically changing forest dynamics and the health of our trees.

A few years ago, I was doing fieldwork in a loblolly pine forest. I was accompanied by another field worker, and, in the monotony of sampling, we began discussing climate change. He said, “Well, even if climate change is real, the more carbon the better…the trees will grow faster.” Besides my initial disbelief, I saw his point. There are studies that show higher concentrations of CO2 do make trees grow faster (to a point and only under some conditions) – but reducing the behemoth that is climate change into “more CO2” is a grand simplification.

For example, the southern pine beetle (SPB) is an insect that has established itself as a major threat to southern forests, especially planted timber forests. Starting in 1998, a four-year outbreak in the Appalachian mountains impacted over one million acres of forest and caused an estimated $1 billion in damage. Historically, the SPB lived in forests from northern Florida up to Virginia – that is until they were recently found in New York. With less frigid winters, the beetle is able to expand its range northward and establish populations there. In fact, scientists believe by 2050, SPB will likely be able to establish itself in southeastern Canada. On top of growing populations of SPB, this expansion also allows them to attack naive trees (trees that have never experienced SPB and, therefore, may not have the tools to mount a defense response).

Climate change is also changing the biology of disease-causing pathogens. Brown spot needle blight (BSNB) is a disease that causes conifers like pines to shed their needles prematurely. Because their ability to photosynthesize is compromised, the disease can lead to stunted growth and mortality. In the southeastern US, BSNB is typically isolated to longleaf pine and was not considered a major forest health issue. In recent years, however, we have seen an unprecedented amount of BSNB popping up in other species such as loblolly pine. The range expansion and jump to different species has been attributed to climate change fostering a more suitable environment for the pathogen. A recent study showed a strong, positive correlation between future climate change scenarios and disease distribution. The study also suggested that areas currently free of BSNB have a high likelihood of disease in the next 50 to 80 years.

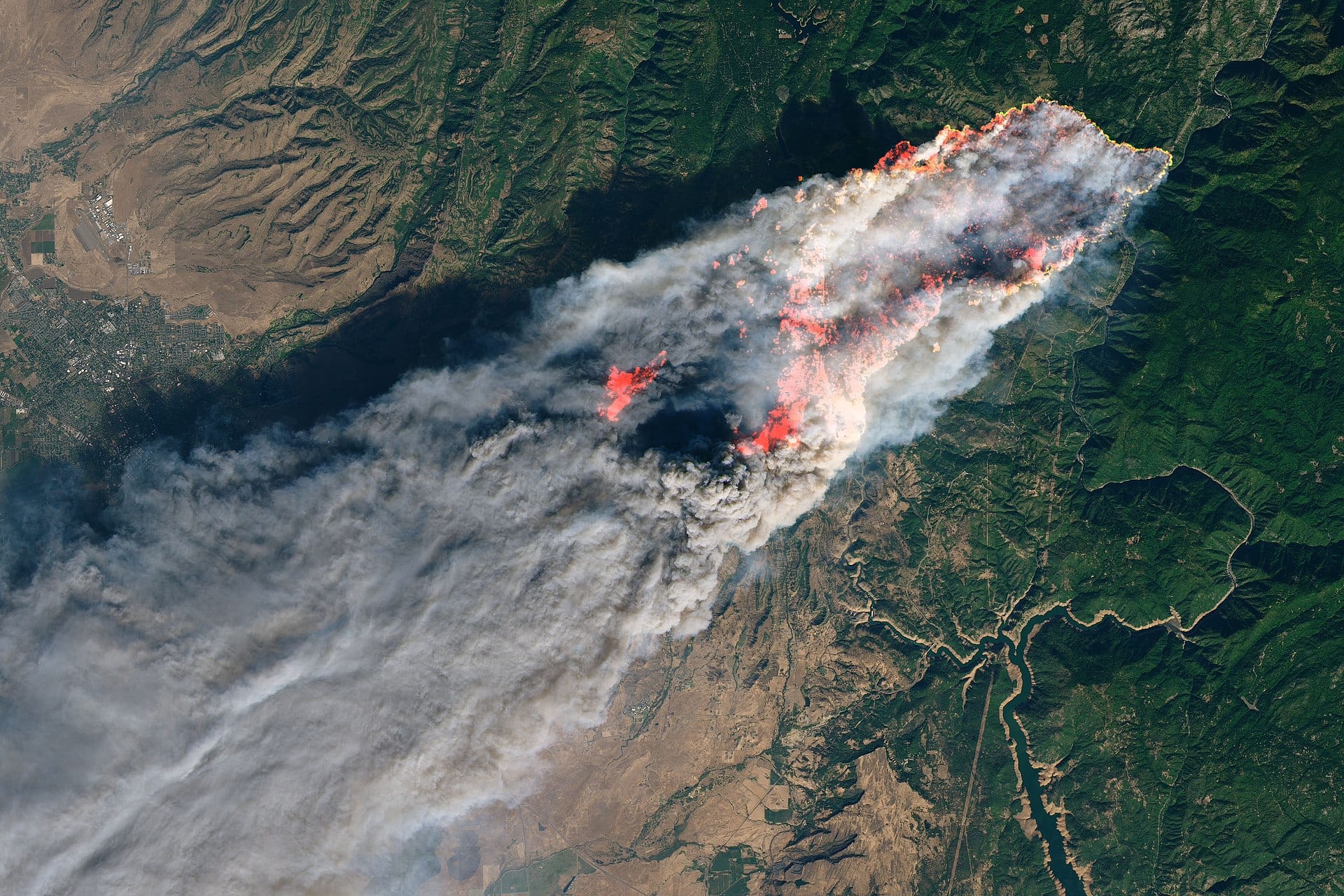

The effects of climate change are not only changing the pests and pathogens; they’re also making the host trees sicker. Climate change brings with it longer droughts, wetter winters, and more severe storms. Trees (and most other organisms on this planet) did not evolve to withstand such environmental extremes, and, as a consequence, our forests are experiencing diebacks like never before. Prolonged drought, for example, weakens the overall health of trees and leaves them more susceptible to attack. In fact, evidence has shown that bark beetles are attracted to drought-stressed trees, which is likely to be an evolutionary advantage for overcoming tree defenses. The same pattern is seen for tree diseases, where the disease tends to be more damaging when a tree is water-stressed.

At this time, the forests we rely on for products, carbon capture, and recreation are being threatened now more than ever before. With an uncertain future, scientists are hard at work in finding strategies to improve forest health by using new technologies, fostering collaborations, and communicating the urgent status to the public. The effects of climate change come in many forms, and broader awareness of this complexity is key to protecting our forests. We may not be able to stop climate change at this point, but you can help keep forests healthy: volunteer with forest clean-up events, get involved with local government, be on the lookout for invasive species, or just hike through the forest with a different mindset. Climate change is bigger than all of us, but forest health can be improved by each of us.

About the Author

Simone Lim-Hing is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Georgia Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources studying the host response of loblolly pine against pathogenic fungi. Her main interests are chemical ecology, ecophysiology, and evolution. Outside of the lab and the greenhouse, Simone enjoys going to local shows around Athens, playing Mario Kart, and reading at home with her cat, Jennie. You can reach Simone at simone.zlim@uga.edu or on twitter @simonelimhing. More from Simone Lim-Hing.

-

Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/March 18, 2021

-

Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/April 1, 2020

-

Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/

-

Simone Lim-Hinghttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/simone-lim-hing/October 26, 2019