“I think my career was negatively impacted by being a woman,†said Ellen Neidle, professor of microbiology at the University of Georgia (UGA), who has a doctorate in molecular, developmental, and cellular biology. “I always thought that women could do everything. It was a pretty big shock to me when I first realized that wasn't true.â€

The phenomenon known as the “leaky pipeline†describes the way in which women become underrepresented minorities in STEM fields, according to an article from the Graduate Student Association at the University of Maryland. If water is poured into a pipe with leaks along its length, a small amount of water will emerge at the end. In this metaphor, the pipe represents the path to a career in STEM, and the water represents anyone pursuing such a career.

“More women drop out of the pipeline in going from Ph.D. student to professor than men,†said Cassandra Hall, a new assistant professor of computational astrophysics at UGA, who has a doctorate in astronomy.

The leaky pipeline affects women in various STEM fields differently. “Women in biological and life sciences represent more than half of the students earning Ph.D.’s, yet most fail to achieve tenure track faculty positions in academia,†according to the Graduate Student Association of the University of Maryland.

In other fields, this disequilibrium begins even before the undergraduate level. Fewer women choose math, engineering, and physics as majors in the first place, according to a 2014 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This may be a self-perpetuating problem, as the low numbers of women going into these fields leaves young women with a lack of role models.

Two common reasons for this phenomenon are that women are more likely to put an emphasis on work-life balance, and that male postdocs are twice as likely to expect their partners to make career sacrifices on their behalf, according to the study.

“I certainly have some friends who are wives who feel like they've given up their careers for their families,†Neidle said.

Women hold only 37% of all faculty positions and only 28% of tenured faculty positions at UGA, according to UGA's 2019 Fact Book. Neidle feels that women are underrepresented because UGA does not foster an environment of retention. She has noticed an increase in female graduate students deciding they do not want to pursue a career in academia. “What does that say about the portrait we're portraying?†she said.

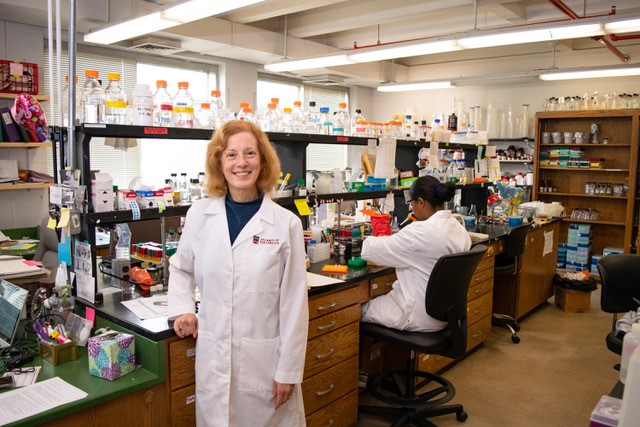

Neidle has been an advocate for supporting women in science at UGA since she began working there in 1994. “I've always been a squeaky wheel, and being a squeaky wheel makes you feel more and more ostracized.†She said that being a “squeaky wheel†means she is often vocal about her complaints when she notices a discrepancy with diversity and inclusion.

At a prestigious scientific conference held at UGA in 2007, Neidle noticed that out of more than 15 world-renowned speakers, only one was a woman. “I complained to the department, and there's always an excuse,†she said. “And then everybody gangs up and argues against me, whether it's on these email lists, or just discounting what I have to say.â€

Neidle's experience of being marginalized by male colleagues is not unique. It is an institutional issue that is perpetuated by underrepresentation of women and reinforced by gender stereotypes. With a lack of role models and support from female colleagues, stereotypes of women being less “intelligent†and “competentâ€, and being more “emotionalâ€, are easily maintained, according to a 2019 study published in the Journal of Neuroscience.

Hall has also experienced and witnessed gender discrimination in her field. “A lot of the time it's not malicious, it's a subconscious bias, but that's why I think it's really important to address the issues,†she said.

Hall recognizes that being white and cisgender puts her in a position of privilege. “I’ve been incredibly lucky in many senses because the challenges that I’ve faced have been mostly offhand comments,†she said. “It seems to happen to my colleagues more than it happens to me, but it could be my own bias that I'm not noticing it's happening to me.â€

Hall noted that she is aware of many issues with bullying and sexual harassment in her field, and that she knows of women who have internalized trauma from these situations who have had to seek therapy. She said it is important to have good networking between women within the STEM fields because it can act as a lifeline in these scenarios. She also said, “it helps to have other women to run ideas past for equity and for making things better, as well as to act as a sounding board.â€

Hall said she feels that being a gay woman sometimes causes people to trust her judgements more than those of her straight counterparts. “It's interesting that society has deemed that because I'm slightly more masculine presenting, that I'm somehow slightly more worth listening to.â€

Hall was awarded a Winton Exoplanet Fellowship in 2018, which she said felt monumental to her both as a woman and as an open member of the LGBT community.

After she got the email about the fellowship, one of Hall's colleagues told her not to “out†herself in her interview. She decided that if Winton has a problem with her being LGBT, then she does not want their money. “I've got thick skin, so it's water off a duck's back to me,†she said.

Neidle said she loves her career and her interactions with her grad students, and that there are aspects of being in academia at UGA that are “really wonderfulâ€. However, she said there are simply certain issues that need to be addressed.

Neidle has been involved with several initiatives to get funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to support increased diversity. She has been in charge of her departmental seminar series for the last few years, where one of her duties is to select invited speakers. “I can make sure that half of the speakers will be women, and that there will be people of color coming in,†she said. “I'm trying to find places where I can make a difference.â€

Neidle said she has learned to pick her places, and to figure out where she can and cannot fight. “There has to be a balance. Some of it is being a squeaky wheel, some of it is fighting for things, and some of it is just quietly changing things you can change,†she said.

Hall said it bothers her when people assume that things naturally get more “liberal†over time. She said that change requires conscious effort, whether it be for civil rights, women's rights, or LGBT rights. “Don't assume that things always get better, because they don't, they are hard won victories by people who often sacrificed a lot to do so,†she said.

Neidle said, “I think having more diversity brings creativity, it brings in different perspectives. You want to share ideas universally across all boundaries, so it just seems obvious to me.â€

Both Neidle and Hall hope to see a future where the demographics of successful people in STEM accurately reflect that of society, and where a person's success is not impacted by implicit biases. Hall said that being aware of these biases is the first step to eradicating them because if you know they're there, then you can do something about it.

Main image credit: Quaerens-veritatem licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

About the Author

Alaina is an undergraduate studying journalism with a minor in French and a certificate in new media studies. She hopes to combine her passions for journalism and science into a career in science communication. In her free time she enjoys camping, live music, and caring for her pet snake Cassini. She can be reached at alainaoregan@gmail.com.

-

This author does not have any more posts.