How might climate change affect the environment in 50 or 100 years? To even begin to answer this pressing question, we need work that can accurately describe changes in the environment to predict the future. Long term ecological research (abbreviated as LTER), describes studies interested in environmental processes that last for at least one year and often much longer. These records are valuable for documenting ecosystem changes, understanding the impact of human land use, and testing scientific questions. Starting and continuing LTER is not easy; the work is expensive and time-consuming due to the consistent labor required and the regular data collection. Often budgets focus on short term experiments that quickly yield results rather than funding LTER. Additionally investigators are reluctant to take on LTER due to the time required to collect enough data to publish, which could jeopardize promotion and career trajectories.

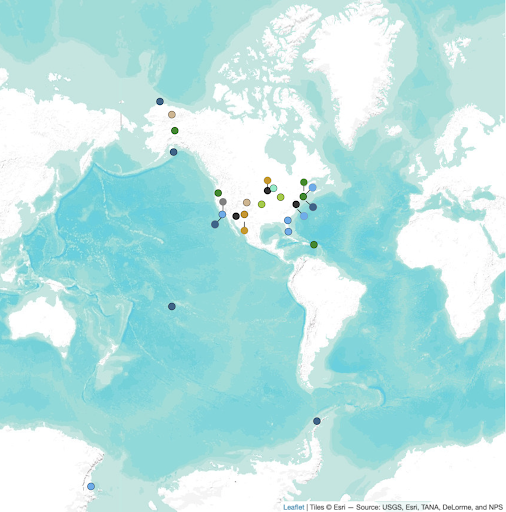

To encourage the development of LTER, the United States government, through the National Science Foundation, has built a framework that funds 28 sites that engage in this work. These sites stretch across the United States, Antarctica, and French Polynesia and represent distinct biomes like coastal, freshwater, grasslands, marine, tundra and even urban. Work done at NSF LTER sites has generated valuable insight into ecological processes. For example, researchers have determined that regular wildfire suppresses plant disease outbreaks and that glaciers are melting as climate change progresses. Another major finding is from the Harvard Forest soil warming LTER site, where researchers learned that higher temperatures disrupt the natural carbon cycle, leading to greater levels of carbon in the atmosphere than previously estimated.

A brief history of NSF LTER Support

The mid to late 20th century in the United States was marked by an increased public interest in environmental protection. Protests erupted in the late 60's in response to highway construction tearing through communities and natural areas. Rachel Carson's groundbreaking book Silent Spring, which documented the adverse effects of pesticides, was published in 1962. The Cuyahoga river caught fire for the 13th time in 1969. Spurred by this, President Richard Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act in 1970 which mandated federal agencies consider environmental impacts when carrying out their duties, which eventually promoted large scale environmental research. In 1974, the joint ad hoc Committee on Ecological Research determined that studies assessing human impact on the environment needed to add a predictive capability, suggesting a need for long term studies. At the time, funding for ecological research was on short timescales due to funding constraints, resulting in limited inferences.

Starting from 1977, the NSF held a number of workshops to develop long term ecological projects and eventually funded six initial LTER sites in 1980 which grew to include 19 sites in the first 10 years. The NSF renews funding for current sites on a six year cycle, with separate calls to add new sites to the network. The most recent addition was the Minneapolis-St.Paul urban LTER site in 2021. One of the most valuable parts of the LTER network is the collection of large swaths of data to describe changing ecosystems. By policy, data collected at the NSF LTER sites is made available with little to no restrictions, allowing for more collaboration and insight outside of the network.

LTER in Georgia

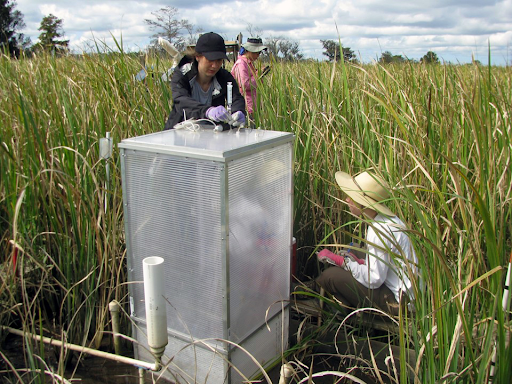

In Georgia, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has observed an increase of 1.11 feet of sea level since 1935 and the US Army Corps of Engineers is expecting a sea level increase of one inches every two years going forward. To study the effects of changing coastal environments, the NSF and University of Georgia Department of Marine Sciences established the Georgia Coastal Ecosystems LTER in 2000. This NSF LTER site monitors the sounds, or bodies of water between land and barrier islands, of Altamaha, Doboy and Sapelo. The SALTEX experiment, started in 2011, is designed to understand the impacts of sea level rise and drought. Researchers use experimental plots where they either allow constant flow of saltwater to simulate rising sea levels or short term pulses of saltwater to simulate effects of drought. So far, the results indicate shifts in soil nutrient levels and a decrease in plant diversity, suggesting that rising sea levels will reduce net productivity of coastal areas and lead to a loss of soil carbon while increasing soil erosion.

The future of LTER

Consistent financial support is crucial to maintaining LTER, but the funds are not enough to support all programs. In 2016, the Coweeta Research program, located in Macon County, North Carolina and partnered with the University of Georgia, was denied renewal funding through the NSF's LTER program and closed in 2021. There are other programs that are not part of the NSF LTER framework, like The Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, that need to rely on other sources of funding, drawing from private and public donations. Some researchers are getting creative with funding their LTER. Gord Mcnickel, a professor in the botany department at Purdue University has used crowdfunding to support their lab's work at the Ross Biological Preserve.

Ultimately, the biggest financial contributor for basic research, including LTER, is the federal government. Decisions at the national level can influence the amount of money that is used to support LTER. Action from the Trump administration limited the power of the National Environmental Policy Act, which could deemphasize federal support for ecological research. This runs contrary to public opinion, which is once again behind protecting the environment. In 2020, a study from the Pew Research Center found that two-thirds of Americans believe the government should focus more on the environment. President Biden indicated support for LTER through climate change research as part of his election campaign and has requested $10.17 billion for the NSF for the 2022 fiscal year, an increase of 20% over 2021. On March 10th, the Senate passed legislation for the 2022 fiscal year, increasing the NSF budget by 4.1% or $8.84 billion. With inflation currently at 7.9%, this increase can be interpreted as a cut in funding for the NSF, and ultimately long term research as a whole.

Additional Links:

The Wired Forest: 30 years of Harvard Forest Long-Term Ecological Research

Long-term ecological research threatened by short-term thinking

About the Author

Inam Jameel is a PhD student in the Department of Genetics at UGA. He is interested in how natural populations adapt to rapidly changing environments. When not in the greenhouse or in the lab, Inam likes to run, attend concerts, watch the Washington Capitals, and do poorly at trivia. He can be reached at inam@uga.edu or @evo_inam.

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/November 17, 2020

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/April 28, 2020

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/December 9, 2019