I spent last summer far from Athens, Georgia, as an intern at the Caño Palma Biological Station in Costa Rica. A small station nestled in the lush jungle of eastern Costa Rica, Caño Palma conducts a variety of long-term wildlife surveying efforts, with the biggest and longest conservation project studying nesting sea turtles. Volunteers and interns arrive from all over the world to work with loggerhead, leatherback, hawksbill, and green turtles firsthand.

Nights at the station began similarly. Between 8 PM and midnight, small teams pulled on all-black outfits, laced up sandy sneakers, and divided up an 8-mile stretch of beach. Using only small red flashlights when absolutely necessary, we patrolled up and down the surf for hours, scouring the sand for any signs of turtle activity.

Often we found only tracks. Sometimes they led nowhere, a so-called “half moon†shape formed in the sand by a turtle deterred–by a rock, branch, or some other reason–from nesting. Other times, we followed the tracks to a nest, which we recorded and flagged, then carefully disguised. If we were lucky, we saw a turtle.

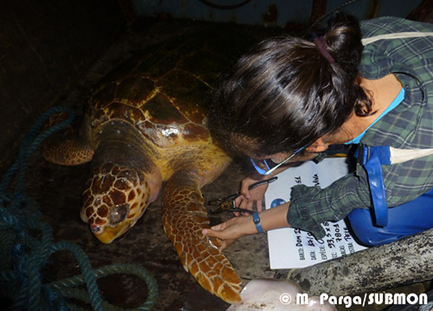

What followed this was a quiet but practiced procedure. The patrol leader approached first to check the stage of nesting. Depending on how much time we had, we took varying size, health, and nest data, but our immediate priority was checking for identification tags on their flippers. While much of a turtle's life outside of nesting remains a mystery to biologists, the tendency of sea turtles to return to the same beach to nest gives a rare opportunity to track the survival and reproductive habits of the same turtle across several years, which many small stations like Caño Palma can achieve through the use of unique exterior metal tags.

After collecting what data we could, we waited until the turtle flopped back into the sea then worked together to disguise both the tracks and nest location. While we triangulated the nest and took its GPS coordinates, no other identification was given to its location. All of this covertness stemmed from the one central issue for Costa Rican research stations: the constant threat of poaching.

Poachers, for the most part, were responsible for our black clothing, lack of illumination, and nest disguises. While poaching can threaten both the turtles and their recently laid eggs, the intentions of a poacher depend somewhat on the species of turtle. Leatherback turtles are so enormous it is unreasonable to poach an entire turtle, while the smaller hawksbills are frequently poached for their intricate shells. All new turtle eggs are vulnerable to poaching, but the eggs of green turtles in particular are a delicacy in the region.

With turtles laying 110 eggs on average across species and prices around $1 per egg, the excavation of a nest can fetch a high sum for a short amount of work. Poaching usually occurs in dark, unmonitored areas of the beach, making it difficult to quantify the exact impact to turtle populations, though some initiatives report poaching can destroy 90% of unprotected turtle eggs. Near Caño Palma, poachers are members of the community and are reluctant to have their faces recognized. Through our presence on the beach, our patrols served as an active, but not complete, deterrent.

Following the night patrols, another patrol was conducted in the early morning. This patrol served to both record activity missed by earlier patrols and observe any nests disturbed during the night. While direct contact with poachers was against policy, a couple times during my internship backpacks were found abandoned and filled with eggs, which we would then empty and relocate.

Poaching like this has been an ongoing challenge to sea turtle researchers globally, but during the Covid-19 pandemic, biologists saw an enormous rise in this activity, due to staff shortages and lack of alternative work for poachers. During much of the early pandemic, only one staff member remained on base at Caño Palma, making it impossible to carry out surveys. This was reflected in stations across the world.

Most of the time, poachers are just people looking for easy work. Little stations like Caño Palma are then uniquely positioned within local communities to directly influence the behavior and attitudes of the locals, which they attempt through local education and outreach initiatives. While poaching and wilful destruction of wildlife is frustrating, conservation efforts have not been deterred, and with Covid-19 restrictions easing more and more people (like me!) are able to help protect these populations. As anthropogenic activity increasingly threatens these environments, Caño Palma symbolizes the hundreds of little field research stations doing big work, continuing to serve as underfunded but invaluable centers for the protection of wildlife.

About the Author

Sahana is an undergraduate at the University of Georgia studying Astrophysics with a Sustainability certificate. When she's not pretending to do her homework, she can be found playing ultimate frisbee or adventuring around Athens. Connect with her at sahana@uga.edu.

- Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/November 15, 2024

- Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/February 14, 2024

- Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/November 11, 2022

- Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/December 29, 2020