When the International Space Station (ISS) reaches the end of its lifespan in 2031, where will it go?

No options for major recycling exist in outer space, so when a spacecraft is decommissioned, there are only three “trash cans” available. The first is a so-called “graveyard orbit,” where spacecraft are blasted away from Earth into orbits far from active satellites. Alternatively, spacecraft are moved into the Lower Earth Orbit (LEO), where they continue to circulate the Earth at high speeds until atmospheric drag brings them to a fiery demise in our atmosphere. Spacecraft too big to burn up before reaching the surface fall to their death near Nemo Point, an area in the Pacific Ocean used to retire old spacecraft like the ISS.

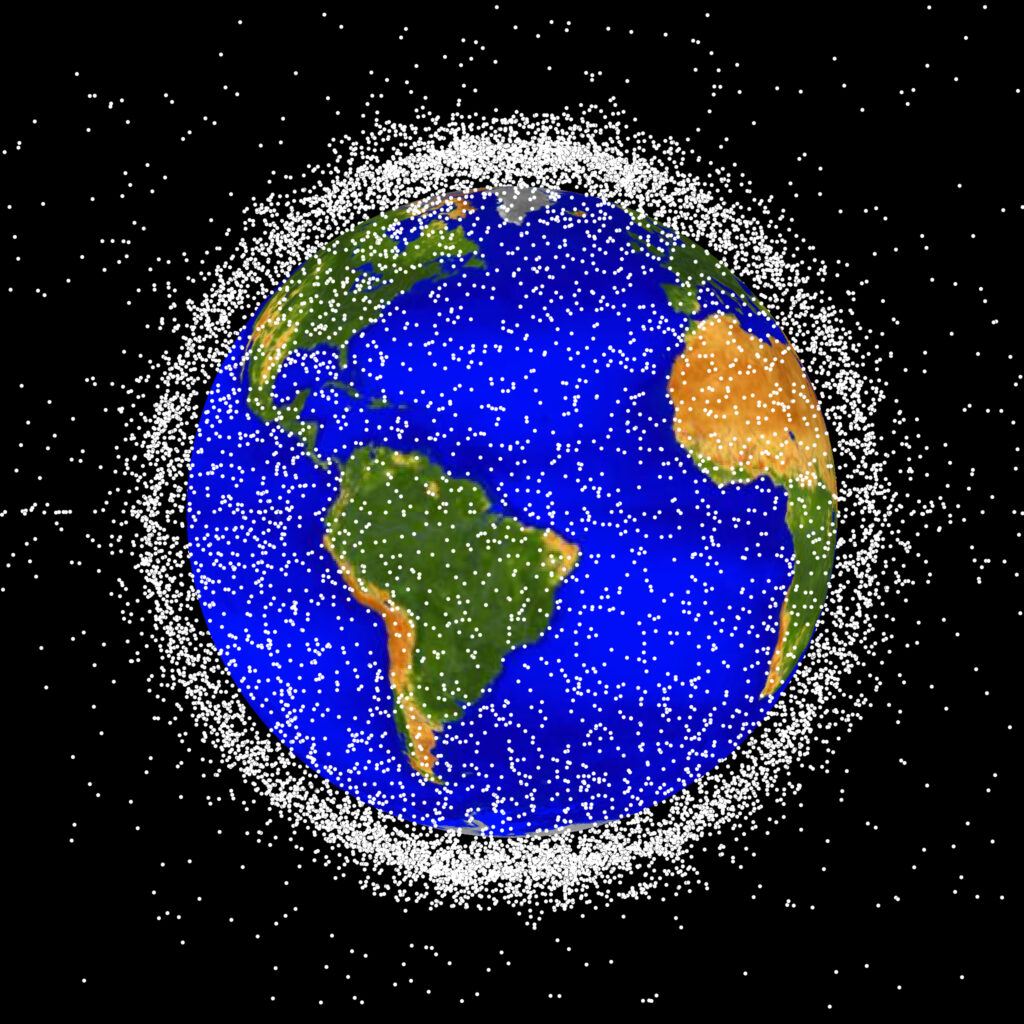

These methods have their drawbacks. Additions to the LEO and the graveyard orbits contribute to the growing body of “space junk,” a phenomenon that has begun to worry many scientists and policy makers. There are currently millions of pieces of debris orbiting in the LEO, most of it composed of human-generated waste, which pose serious risks to both manned and unmanned spacecraft like our commercial satellites. Decommissioned satellites in lower orbits are particularly susceptible to collisions and explosions from residual fuels and gasses, creating further debris. Meanwhile, every kilogram wasted from an expired spacecraft body represents an equivalent kilogram of money, manufacturing, and fuel to be relaunched into orbit.

In response to these concerns, the National Aeronautics and Space Association (NASA) held the “Orbital Alchemy Challenge” in spring 2022, challenging innovators from all educational and professional backgrounds to submit novel proposals related to the reuse of spacecraft above one metric ton, like the ISS, after they have been decommissioned.

WidgetBlender LLC, a small space system engineering company based out of Virginia, won first place and the $25,000 prize with their proposal “SAFER: Satellite After Fully Enclosed Recycler.” Their concept, essentially an in-space satellite enclosure with a focused solar melting tool, aims to break down a satellite into aluminum and titanium components that would then be available for future in-space manufacturing projects. The chief engineer on the project, Jeff Morse, has followed “space sustainability,” the burgeoning field that the Orbital Alchemy challenge grew out of, since the 1980s.

Despite its success at the proposal stage, Morse says he doesn’t necessarily “believe this [SAFER] recycling concept has a lot of value,” at least in the financial sense. He highlights that launch systems already exist, like SpaceX’s Starship prototype, which can “deliver high quality, well tested, and pre-integrated” equipment to spacecraft in the LEO “for far less than you can make from orbital scrap.” In short, it doesn’t seem worth the hassle to try to take things apart, at least right now.

But why? One of the biggest obstacles to future development of recycling proposals like SAFER is that the vast majority of our current spacecraft are simply not designed to be reused. Engineers have been building spacecraft for years with the understanding that what went up would not come down–at least not in a usable form.

Today, even though the ISS itself is unlikely to be recycled, this single-use mindset has been changing. In 2012, the private company SpaceX debuted their reusable rocket launch program, a move that has since spurred huge interest in reusable launch technology in the private sector. Internationally, the European Space Agency has been particularly vocal about their desire to be “space-debris neutral” by 2030, funding proposals for potential in-orbit satellite servicing stations and in-orbit manufacturing facilities. Meanwhile, many smaller start-ups have been focusing on proposals to actually clean up orbital debris, with concepts ranging from giant harpoons to space garbage trucks. The creation of the Orbital Alchemy Challenge symbolizes the global efforts of the space community towards a new ideal of a “circular economy in space.”

This push has reflected in the legal landscape as well. The United Nations released guidelines in 2007 on mitigating orbital debris, and there has been a growing international call to update the 1967 Outer Space Treaty to reflect new sustainability concerns. In the US, the bipartisan ORBITS Act was introduced to the Senate in September, proposing a novel program to reduce the amount of space junk in-orbit. This bill follows the DEBRIS Act in March 2022 and the Federal Communications Commission’s publishing of new guidelines for de-orbiting spacecraft. With the single-use paradigm shifting, the global space sector is re-examining the way we as humanity approach both sustainability and our future in space. The future of the SAFER concept remains unclear for now, but all of NASA’s big future plans: building a new ISS, establishing a sustained base on the Moon, and sending humanity to Mars, depend on novel ideas on reusable, long-lasting spacecraft design. As we enter a new age of space exploration, we have reason for hope that when the next ISS retires, it will have a different future.

About the Author

Sahana is an undergraduate at the University of Georgia studying Astrophysics with a Sustainability certificate. When she's not pretending to do her homework, she can be found playing ultimate frisbee or adventuring around Athens. Connect with her at sahana@uga.edu.

-

Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/February 14, 2024

-

Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/April 15, 2022

-

Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/December 29, 2020

-

Sahana Parkerhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/sahana-parker/May 13, 2020