Driving down any rural road around this time of year, you’re likely to see rows on rows of corn blowing in the wind. You might notice that they look like twins of each other, almost exactly the same height and precisely the same color. That uniformity is also why corn lovers can walk into near any grocery store in the US and confidently pick up an ear of corn knowing it will be the delicious juicy big lump with knobs that recently inspired the viral song “It’s Corn”.

It’s Corn – original short ft. Tariq, Recess Therapy, and Schmoyoho

This viral song led me to wonder, how did corn become such a BIG lump with such juicy tender knobs? To understand that we need to start from the beginning, the domestication of corn, also known as maize.

Domestication of Maize

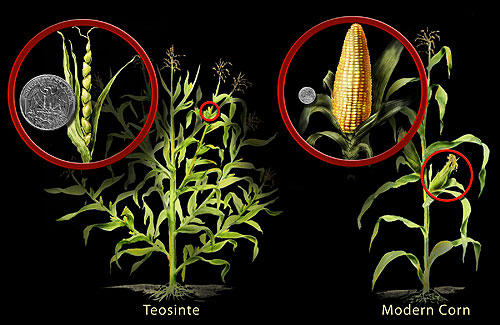

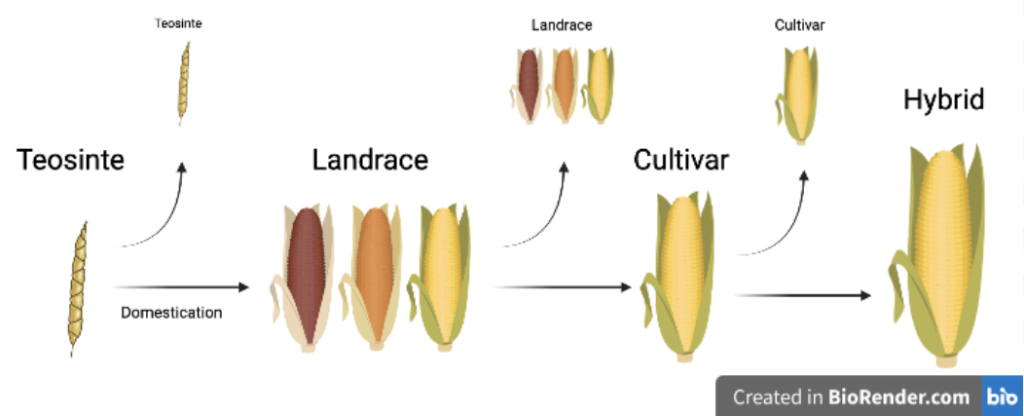

Before maize was the big juicy lump with knobs that we know today, it was something much less appetizing. In the Balsas Valley of Central Mexico about 9000 years ago, humans began the slow process of domesticating teosinte, a wild grass species. Teosinte has small ears holding just 5-12 kernels encased in a hard nut-like shell. If you tried to eat teosinte off the cob you’d be liable to break a tooth!

The stark difference between the two led to 30 years of scientific debate over their true relationship. It seems likely that 9000 years ago humans were making corn meal by grinding the early maize kernels into a flour. Over the next ~7000 years, each growing season humans selected the early maize plants with the largest ears and the softest kernels, that were easiest for them to grow and process. One might say they were choosing the biggest lump with the most knobs. Over many many generations of this selection maize arrived at what we recognize today, a domesticated crop plant.

The Landrace Era

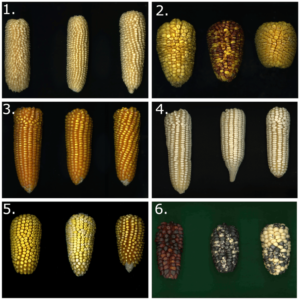

As maize was becoming the plant we all know today, humans began carting it around with them as they migrated throughout the Americas. As they did so, they exposed their maize to novel weather patterns, soil types, light intensities and durations, and evermore environmental factors. As they already had for many generations, farmers chose the plants that did the best in their new environment and planted those seeds the next year. Over time this resulted in maize plants that were locally adapted, meaning they did best in their specific environment. It also resulted in maize plants from the same area looking and behaving very similarly. These are called landraces in maize. Heirloom varieties, a popular seed type in tomatoes, is a similar concept. Today, maize landraces are still grown in some areas, though their use is diminishing in favor of more uniform varieties that typically produce higher yield.

The Cultivar Era

Maize persisted in the form of an umpteen number of landraces until around the 1800s when farmers began selecting for plants that did well across a wide range of environments and were more uniform. These new varieties are called cultivars. Cultivars were developed by individual farmers selecting corn plants that fit their personal preferences. For example, one particularly prominent maize cultivar was selected to be harvested with minimal strain to the wrist as the creator was an artist. Over time, the cultivars that gained popularity were those that did well across many environments.

By the late 1890s it was estimated that there were about 540 maize cultivars being grown in the US and Canada. Around the early 1900s a new cultural phenomenon swept the nation, the corn show, a state fair like event where maize cultivars were judged on several criteria including how similar ears of the same cultivar were. Uniformity was prized in part because it streamlines harvest and allows farmers to better predict their yield. These factors pushed maize breeders to generate inbred and eventually hybrid lines.

However, maize cultivars continue to be used particularly in Mexico and some countries in Africa as it is easier to produce seed for the next generation.

The Hybrid Era

In the 1920s and 30s, there were 367 different inbred lines considered “outstanding” coming from 96 cultivars. Inbreds are distinct from all forms of maize that came before them because they are true breeding, meaning if you cross two maize plants of the same inbred line together, the offspring will look nearly identical. This is comparable to breeding dogs; if you breed a pug dog with a pug dog, you will always get pug puppies.

Corn farmers quickly found that if you cross two different inbreds together you get super strong healthy corn, a phenomenon referred to as hybrid vigor. This would be like crossing a 20lb pug to a 20lb beagle and finding that all the puppies weigh 50lb and are 10 times tougher, stronger, and healthier than either of their parents. This is where maize breeding stands today, nearly all the corn you find in the grocery store is hybrid, meaning it is the equivalent of a puggle.

It took about 9000 years of farmers carefully choosing the maize plants with the biggest lumps and the juiciest knobs before we got to the delicious corn that we’re all singing about today.

About the Author

Meghan Brady is a genetics Ph.D. student whose research focuses on selfish genetic elements in maize. She is passionate about increasing diversity equity and inclusion in STEM fields. When outside of the lab she enjoys hiking and tending her many house plants. You can contact Meghan at meghan.brady@uga.edu.

-

Meghan Bradyhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/meghan-brady/November 2, 2021

-

Meghan Bradyhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/meghan-brady/

-

Meghan Bradyhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/meghan-brady/December 8, 2020