Bunny-pocalypse

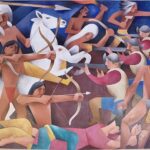

Image depicting the spread of rabbits in Australia from Alves, et al. 2021 (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND).

In 1859, a wealthy English settler named Thomas Austin imported 24 European rabbits into Australia as game for shooting parties. This seemingly small event would soon reshape the continent. Thomas Austin was a member of the Acclimatisation Society of Victoria in Australia, one of many clubs advocating for the introduction of non-native species around the world. While it is common knowledge for many today that introducing non-native species can be harmful to native species and their ecosystems, in the 18th and 19th centuries, such organizations were in vogue. Volunteers would receive medals for their efforts to establish breeding pairs in colonized territories, especially in places like Australia and New Zealand where colonizers claimed that local animals were “deficient.” The rabbits that Thomas Austin brought to Australia as part of his shooting parties soon slipped out of his pasture and bred like rabbits.

The rabbits rapidly spread across the country, spreading 60 miles per year. By the beginning of the 20th century, they were described as “a gray blanket” covering the country. By 1950, there were 600 million rabbits in Australia, and they had spread across almost the entire continent. To put this into context, after being introduced from France to Britain, it took rabbits 700 years to cover the country, which is just 1/25 the area of Australia. The rabbits competed with livestock, spread weeds, accelerated erosion, and caused many farmers to abandon their homesteads. Initial efforts to control their spread and disruption of native wildlife proved fruitless, leading to more creative measures.

Fighting a Plague with a Plague

The release of myxoma into Australia (CC by 3.0)

In 1950, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) experimented with an ambitious and creative approach to controlling the rabbit plague: introducing its own plague on the rabbits, a method known as biocontrol. Researchers introduced rabbits infected with myxoma virus into the wild, an incredibly deadly virus for these introduced pests. It was the world’s first successful biological control program for a mammal, killing nearly 100% of rabbits in affected areas after a few weeks. Within just two years, it would kill an estimated half billion rabbits and spread across most of the continent. However, each successive year, more and more rabbits would survive. While most rabbits died, the rabbits that did manage to survive the infection or avoid it altogether were left to reproduce. This led to more rabbits being able to survive subsequent outbreaks. The virus began to evolve too, becoming less dangerous to the rabbits! If a virus killed all of its nearby hosts before it could spread to more rabbits, that strain would die out. Over time, less severe strains of the virus became more common. The diminishing efficacy of the virus each year was a major issue, but there was a more immediate problem: people started to get sick.

An Unfortunate Coincidence

Just a year after the myxoma virus was introduced to Australia, an outbreak of a novel disease in the same area of Victoria in Australia caused panic. People started coming down with a mysterious illness that caused fevers, headaches, exhaustion, vomiting, and convulsions. 17 people died, and many were left with neurological damage. The public became concerned that the myxoma virus was spreading to humans. Scientists recognized the similarity between these cases and other outbreaks that occurred in 1917 and 1918, but the public was unconvinced. A politician from the afflicted region challenged Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet to prove that the myxoma virus was harmless. Instead of pushing back by claiming scientific evidence was already strong enough, Burnet and two other scientists, Drs. Ian Clunies-Ross and Frank Fenner, injected themselves with enough myxoma virus to kill up to 1000 rabbits. Through this dramatic presentation, they proved that the myxoma virus had no effect on humans and could not be responsible for the mysterious outbreak.

Today, scientists propose “gene drives” for eliminating malaria and invasive crop pests, geoengineering to mitigate the effects of climate change, and novel vaccination technologies to address global pandemics. Similar to the 1950 introduction of myxoma virus, people are often scared of these new developments. Individuals often self-identify as “believers” or “skeptics” of science, treating the other group as foolish. However, the safety of myxoma virus’s introduction was proven not by discovering the true source of the mysterious illness afflicting the area. Instead, it was shown through the perseverance of a team of scientists determined to address head-on concerns about the safety of their efforts. In fact, it wasn’t until thirty years later that Dr. Eric French succeeded in isolating and characterizing the virus causing the mysterious illness, Murray Valley Encephalitis. The mysterious virus was spread by mosquitos who spread the virus from infected waterbirds, and it was endemic in swamps nearby, where it spread during heavy rainfall.

While myxoma continued to reduce the population of rabbits across Australia, rabbit populations eventually stabilized as the virus became less deadly and rabbits became more resistant. The initial effectiveness of the first biocontrol agent, combined with scientists’ readiness to address public outcry and concern, had built trust among Australians, and the CSIRO introduced another virus, the Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Virus (RHDV), in 1996 to help bring back down rabbit populations after they developed resistance. RHDV kept rabbit populations low for a decade before resistance began to appear yet again. The CSIRO continues to leverage a combination of biocontrol and traditional methods to control rabbit populations and maintains a relatively steady population of rabbits in the country. However, their efforts were almost stymied at the start due to an unfortunate coincidence. The project would have likely been shelved after the first outbreak of myxomavirus had it not been for the scientists who listened to public concerns and addressed them head-on; it would be wise to follow their lead.

About the Author

Guppy is a third-year bioinformatics Ph.D. student. They have a master's degree in statistics from NC State University, an undergraduate degree in mathematics from Clemson University, and spent a few years working for TIAA as a data scientist before heading to UGA. Their research focuses on studying the evolution and spread of SARS-CoV-2 and highly pathogenic avian influenza using statistical and computational methods. Outside of the lab, Guppy can be found bouldering at Active Climbing, reading science fiction and history, going on hikes with their puppy, Zoya, roasting and drinking coffee, or playing tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons.

- Guppy Stotthttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/guppy-stott/

- Guppy Stotthttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/guppy-stott/November 30, 2022

- Guppy Stotthttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/guppy-stott/November 16, 2021