Secretariat entered the 99th running of the Kentucky Derby as a heavy favorite, posing 5-to-2 odds. Thus, It wasn't unexpected when the large chestnut colt set the new course record at 1 minute and 59 â…– seconds, but few could imagine the record would still stand today, 45 years in the future. Even Justify, the most recent Kentucky Derby winner, posted a measly 2:04 on the 1 ¼ mile track at Churchill Downs (albeit on wet track conditions). This begs the question, why hasn’t there been a faster horse since?

For centuries, the answer for fast horses has been breeding. All race horses, or thoroughbreds, stem from the three foundation sires: stallions from Arabian, Turk and Barb ancestry. Each of the foundational sires contributed a desirable quality, such as lighter bones and smaller, quicker frames. Combined with the larger english mare, the foals resulted in an intermediate sized, fast but muscular race horse. This trend of selective breeding continues today, with horse racing as a complex world of pedigrees and stud fees. As thoroughbred foals are registered at birth, it's often easy to track a horse’s lineage to a champion racehorse. While Justify and American Pharoah, the Kentucky Derby winner in 2015, share multiple titleholders in their genealogy, this “pick and pray†method using lineage may soon fall out of favor due to modern science.

Since sequencing the horse genome in 2006, breeders can take advantage of a more targeted approach to breeding. Sequencing was initially used for mapping equine genetic diseases, but eventually led to efforts discovering genes related to speed. Dr. Emmeline W. Hill, is credited with associating variants of the myostatin gene with stamina and speed. Dr. Hill's work paved the way for a boom of genetic testing for thoroughbreds to determine if they contain the variants of genes, or alleles, best associated for short or long distances, turf or dirt racing, and other performance metrics.

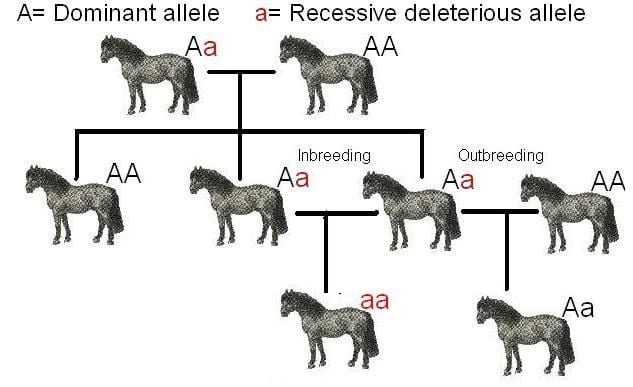

With such technological advances, should we start taking bets on the expiry date of Secretariat's multiple records? Maybe not so fast. Upon sequencing the genome, researchers have also uncovered a distinct level of inbreeding, most likely due to the shared parentage of all thoroughbreds. Inbreeding can increase the likelihood of inheriting undesirable alleles, resulting in detrimental physical characteristics, such as weaker bones or diseases. Alternatively, selective breeding might have removed alleles contributing to speed in thoroughbreds, ultimately limiting the effect of breeding, even when knowing what genes to consider. With race times not improving, it seems plausible to ask, is selective breeding actually improving horse racing? Or is there a biological limit to selective breeding, and have we hit it?

Outbreeding is often used to import beneficial alleles, often resulting in better performing individuals. Likewise, perhaps the introduction of a second cohort of foundational sires from other breeds is needed to incorporate genetic diversity in thoroughbreds in order to achieve faster times. Crossing breeds, however, takes a considerable amount of time. Scientists from the Argentinian biotech company Kheiron are instead looking to utilize gene editing technology to speed this process up. Interestingly, The International Federation of Horseracing Authorities have already banned the use of genetically modified horses, whereas other equestrian sports have already embraced cloning of horses.

Discoveries are continuously being made on what contributes to speed. While genetics is accepted as only half of the equation for racing performance, along with proper nutrition and training, it receives most of the glamor by means of the flashy and often lucrative nature of selective breeding. Although it might be difficult to predict how fast tomorrow's horses will be, science will always spur the sport along.

Further Reading/Listening:

Can Science Breed the Next Secretariat? By Adam Piore and Katy Williams

In the Gate Podcast #354, It's all in the genes

Featured image: Horse race by Butler by Cbaile19 via Wikimedia Commons Licensed under: Public Domain.

About the Author

Inam Jameel is a PhD student in the Department of Genetics at UGA. He is interested in how natural populations adapt to rapidly changing environments. When not in the greenhouse or in the lab, Inam likes to run, attend concerts, watch the Washington Capitals, and do poorly at trivia. He can be reached at inam@uga.edu or @evo_inam.

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/March 18, 2022

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/November 17, 2020

-

Inam Jameelhttps://athensscienceobserver.com/author/inam-jameel/April 28, 2020